Thirty Rooms To Hide In (10 page)

Read Thirty Rooms To Hide In Online

Authors: Luke Sullivan

Tags: #recovery, #alcoholism, #Rochester Minnesota, #50s, #‘60s, #the fifties, #the sixties, #rock&roll, #rock and roll, #Minnesota rock & roll, #Minnesota rock&roll, #garage bands, #45rpms, #AA, #Alcoholics Anonymous, #family history, #doctors, #religion, #addicted doctors, #drinking problem, #Hartford Institute, #family histories, #home movies, #recovery, #Memoir, #Minnesota history, #insanity, #Thirtyroomstohidein.com, #30roomstohidein.com, #Mayo Clinic, #Rochester MN

of her child begging her to Mama

Mama do something Mama.

“January, February, March. . . “ he quails.

Once again she holds the father still

with her stillness

and goes on peeling carrots with her fingernails.

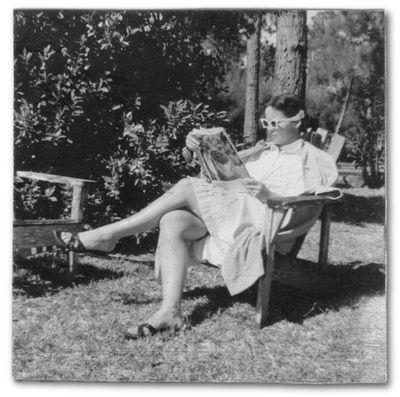

Myra on the shore of Lake Winnemissett in Deland, Florida, visiting her parents in 1962.

It always happens so fast.

Mom’s making dinner and you’re having a snack at the kitchen table maybe thinking about Spider-Man or Dare-Devil, and a rabid dog leaps gracefully up on the table and walks down the length, grinning through its foam.

Maybe something else will attract its attention, you think, maybe somebody will break from the pack and try for the woods. You freeze. You don’t even move your eyes. You stare into the pattern on the plate, into the flowers, past the bee.

When Dad had a drink he became predatory. Some drunks get amiable, some maudlin, all of them stupid; but Dad attacked. He looked for something to piss him off and chewed until he drew blood.

One drink said, “Oh, sounds like somethin’ Momma read in one of her

books

, am I right, boys?”

The second drink said, “Maybe you boys would’ve had your homework done if Mama wasn’t writing to

Grandpa

all day?”

By the bottom of the third drink he was taking street-fight swings at Mom’s character. “MAMA WANTS TO VOTE FOR JACK KENNEDY BECAUSE HE’S SUCH A PRETTY MAN, ISN’T THAT RIGHT, MAMA? WHY DON’T YOU JUST GROW UP?!?”

Kip, today

One of the very first times I saw Dad drunk and abusive with Mom was right after the election in 1960. I was 13. It was in the kitchen. Mom was standing over the stove making soup. And Dad was drunk, berating and belittling her for voting for Kennedy.

I remember Mom just looking up at the ceiling, stirring soup, and crying. Dad was using swear words and yelling at Mom for, God, what? An hour or so? I retreated upstairs to take a bath but left the door to the bathroom ajar so I could hear the yelling from downstairs. It scared me. The next morning I remember asking Mom, “Are you guys gonna get a divorce?”

Most of us did not see the early years of abuse. Much of it happened late at night and down in the kitchen or living room, spots chosen by Mom because they were the farthest away she could get from the bedrooms of her six boys. She would sit on the couch in the living room and let him rage.

“It was usually a matter of just waiting,” she says. “Waiting until he got that last drink in him and would simply tip over.”

The rages flamed hotter and burned longer and over time Mom, like the caretaker of an old furnace boiler, learned tricks to keep him from exploding.

“When he really got going I would drop my eyelids half-way down,” remembers my mother. “If I completely closed my eyes I got in more trouble, because it looked like I was asleep or was shutting him out. I found by closing my eyes half-way he wouldn’t take it as insult and, for me, it was sort of like covering your eyes at the scary part of the movie.”

Roger returned home every night and picked up where he’d left off, coming around to the same subjects again and again, pawing at his prey, searching for that smell to set him off.

“When he came home, I had my letters hidden away, my books put away.” But no matter how safe she made the room he always found some purchase for his anger. It was always the same things: how “easy” Mom was with his money, the letters she wrote to Grandpa, the books she had her nose in, the trips she wanted to take to her parents. One autumn his preferred feeding spot was by the front door where we tied our shoes before school; none of us could lace up fast enough for the famous doctor, a failing he would point out with humiliating comments. When Mom recognized the pattern she bought us loafers.

Money was the big flashpoint. He’d worried about it for years. Even in 1953 Myra was writing, “Roger is in one of his recurring dumps, depressed about money and the lack of it. Says he sees no future for an extra dollar for pleasure for the next 15 years.”

Yet it seemed his fretting was never that of a man but of a child whining, of wishing things were different, and demanding somebody fix things. Mom remembers, “He resigned any authority position long ago. Left every decision to me – even regarding little things like getting the snowplow to come or what to do when a teacher sent home a note about misbehavior. He’d say ‘It’s your problem.’”

The other landmine was “the trips to Florida.” The plural “trips” makes too much of it considering that my mother visited her parents in Florida a total of three times after moving to Rochester in 1950. Yet every time she proposed a visit home, the night would end with Roger hoarse from drunken rage. The next afternoon he’d pick the subject back up and rage for hours until finally Mom would go to the train station downtown, cash in the tickets, put the money back in the bank and show him the receipt. Roger would then go back to the station, buy

another

set of tickets, force Mom to take them and then rave when she took the trip.

In 1961, another trip was cancelled.

Mom, today

I approached your father that spring about my taking a few days to visit the Civil War battlefields of Chancellorsville or Gettysburg with Poppa. Roger’s response was that whiny fretfulness which worked itself into wide-ranging wrath, no longer complaining about my proposed trip but, as usual, berating me with the battery of charges regularly leveled. I gave up the plan rather than face prolonged trouble before and after such a trip. I don’t remember how I told Poppa that I couldn’t make the Gettysburg trip. I probably sent a wire merely saying I couldn’t go. No explanations. But this time my short note so troubled my folks they phoned our neighbor, Betty Hartman, to find out if I had been taken to the hospital or hurt in some way. I still hadn’t the courage to tell my mother and father the real reason.

There was never enough in the bank for Mom to visit her parents, yet when Dad wanted a vacation, money wasn’t an issue. Even here Dad found material for anger – Mom was scared of flying and preferred traveling by train

.

“I couldn’t decide which was worse,” she remembers. “To endure my own anxieties while flying or his psychotic ravings aboard the train.”

There were other reasons to dread going on a trip with Dad. Away from the eyes of the family his vitriol and outrages went up a level. Mom remembers a night in a hotel room when Roger threatened suicide, saying he was going to jump out of the hotel window if Mom wouldn’t “change,” wouldn’t “grow up!” He went so far as to open the window and put his foot on the sill. Even with the possibility of a similar episode, she left on another trip with him. It was probably better than keeping him near her boys.

In 1985, as part of an assignment in her writing class, Myra wrote this stream-of-consciousness essay about that trip.

Myra remembers the trip to Chicago

She sat there in that Chicago restaurant uneasy in the elegance, uneasy in the thought she’d probably have to find her way back to the hotel alone. He was cranking up toward another attack. One drink after another. The persuading her to go along with the drinks and her refusal only inflaming him, sending him to faster drinking and more vicious abuse. None of it new. All the same old stuff. That was the real nightmare: the having to hear the same things over and over again, knowing there was no way to protest, no words to deny, no logic to pursue, no way to stop him once he’d begun. Efforts to make him stop only angered him, made him talk louder, made him threaten more. Though only a few of his threats were ever carried out. Only his threats against her. A threat against a waiter or a train conductor or a passing driver or his boss or a neighbor… none of these threats were ever directly made, never carried out, only announced to her in his ripping voice, the ripping that tore into her and bled her and left her silent, screaming in her head to stop stop stop, staring straight ahead or half closing, unfocusing her eyes. The waiter had not brought that third drink fast enough, obsequiously enough. So he lashed out at her for over-tipping the waiter, and started in at the beginning of the record again, telling her what a total failure she was as a wife, as a mother, losing her mind she was, fast, and would soon have to have the children taken out of her care. Why wouldn’t she grow up, for god’s sake! Grow up! And on and on and on and on and the people at nearby tables beginning to listen, beginning to try not to listen, beginning to be annoyed at his monotonous voice. And when the meal came he just ordered another drink, threw it in himself, put down money which might cover the bill, came as near as ever to throwing the table over into her lap but hadn’t the final guts for that much open defiance of the rest of the world; just of her. And left. Left as he’d left her times before, often in strange cities. Left her again without a thought to her getting safely back to the hotel. Left. She always carried extra money, hoping it would be enough. She paid the bill. There wasn’t enough to get a cab back to the hotel. But if one doesn’t get too far from the lake and the street where the hotel was, it’s not too hard to find the way back alone, along Michigan Avenue. So she walked. Walked in the city with her country-girl fears alongside. Walked in the dark, fearing every footfall she heard behind, fearing every figure that approached. Huddled into herself, holding her hands so that any mugger could see she had no pocketbook to steal. Counting the blocks backward from how she’d counted them when they left the hotel… 19… 18… 17… where he was didn’t trouble her. She walked most of the way back to the hotel without thinking about him, except to hope he wouldn’t be there when she got back. She wanted a quiet bath. A long bath to clean in. But first she had to get there… 12… 11… 10… 7… 5 … a lifeline from here to the hotel. She could take a taxi from here probably but still wasn’t sure the few dollars in her pocket would be enough and a final humiliation from a cab driver she didn’t need. She was afraid even of cab drivers here in Chicago after dark. She was a small-town girl and wasn’t sure anything or anybody in Chicago was really safe. And yet, for these last few blocks, she was safe from him.