Thirty Rooms To Hide In (11 page)

Read Thirty Rooms To Hide In Online

Authors: Luke Sullivan

Tags: #recovery, #alcoholism, #Rochester Minnesota, #50s, #‘60s, #the fifties, #the sixties, #rock&roll, #rock and roll, #Minnesota rock & roll, #Minnesota rock&roll, #garage bands, #45rpms, #AA, #Alcoholics Anonymous, #family history, #doctors, #religion, #addicted doctors, #drinking problem, #Hartford Institute, #family histories, #home movies, #recovery, #Memoir, #Minnesota history, #insanity, #Thirtyroomstohidein.com, #30roomstohidein.com, #Mayo Clinic, #Rochester MN

A photo my father took in New York City the night JFK was assassinated.

Mom writing her parents on November 22, 1963

It is 10:30 p.m. and I am tired. But before I leave this day, it is fitting I should write down its date, as it is one none of us will ever forget. So exhausted am I in mind and spirit I cannot find other words. Good night, my dear ones. I know how much this day’s infamy has shaken you.

My memories of JFK’s assassination want to come in shivering from the cold of a Minnesota November and stand by the big furnace in the Millstone’s basement. It’s been turned on since October and you can see the flame in its belly through the slots in the iron door, roaring orange to send steam up four floors to distant radiators.

Outside in the valley, thin not-quite-winter snow blows through the fields of cut cornstalk. In the yard, our secret summer places are abandoned; June’s bicycles are in the garage, July’s toys in the bushes under a layer of leaves and frozen crust. Even October’s color has flown south. Everything about November 1963 is in black and white, like the news shows on the television set in Dad’s study.

Down at the school in Mrs. Maus’s fourth grade classroom, and up on the wall above pictures of pilgrims, Indians, and turkeys, is the intercom speaker. It is from here our principal, Mr. Patzer, announces, “Boys and girls, I’m sorry to say the President of the United States has been shot and killed. There will be a period of national mourning and school will be dismissed for the rest of the day.”

There is a cold quarter-mile walk home with brothers Collin and Danny, up the steep hill and past the Hollenbeck’s. Soon we are clomping into the Millstone, peeling parkas and dropping mittens. Roger and the oldest three are out of town – on a sightseeing vacation in New York City – and so we call for Mom, breathless to tell her the news. She answers from Dad’s study where we find her in front of the TV. There are no cartoons, no commercials, just the man with the black glasses sitting at the desk with the phone on it and talking in that voice adults use when something really bad is happening and they don’t want you to feel the way they feel.

It’s not until we’ve been in the study for a while and seen the look in Mom’s eyes that we realize something big and terrible has happened. The country’s father was suddenly gone and the world wasn’t as safe a place as it was at lunchtime in the gym.

By bedtime, a light snow is falling.

* * *

Brother Jeff, today

On November 21, 1963, the night before it happened, Dad and we three oldest boys had gone to New York City, just to visit. Did the usual stuff – top of the Empire State Building, toured NBC, watched the taping of a TV show, “The Match Game.”

That evening the four of us were at dinner in a little restaurant. Dad was across from me and I remember it was a tense dinner. I think Kip and Dad were having one of those discussions that bordered on an open argument. Dad was boozing and I remember he said none of us should “get nervous and start masturbating.” There were other demeaning remarks, but that’s the one I remember. Somehow, Dad became so irritated with Kip he suddenly told Kip and me to just go; go off and do whatever we wanted. Dad got up, took Chris and left. I remember watching them cross the busy New York street and disappear.

The next morning, the 22nd, Kip was too pissed off at Dad to stay any longer and left for Minnesota. Dad, Chris, and I took a subway downtown to see the Statue of Liberty. It was there on the train someone told us JFK had been shot.

We never went out to the Statue of Liberty. Instead we stood along the wrought-iron fence in Battery Park listening to someone’s radio. That night, Dad went out and took pictures of Broadway. All the advertising lights were off, restaurants were closed, and there was very little traffic.

Brother Kip, today

I was sitting in a plane at O’Hare when the captain announced Kennedy was dead. A stewardess standing a few feet up the aisle instantly dropped her face into her hands and began to weep.

Mom, November 26, 1963

I write this date and there is too much and nothing to say. This is the day after his funeral. The ranks have closed up and we move on. This has been such a shattering event it has left a scar and we are changed by it. No one of us is the same person we were last Friday noon. I am still dazed – I cannot write about it – yet we talk of nothing else and think of nothing else.

Kip was alone in Chicago when he heard the news. Once home, he climbed into the car and we never spoke (other than our mutual “Have you heard?”) and continued listening with horror to the radio.

Roger called from New York City about 3:00 to say he and the other two were leaving – and there was no longer any pleasure in being there. They were on a subway when someone gave them the news – they had only moments before left NBC where they had been watching the news being hung in great sheets. One of the newspapers they brought home was an “Extra,” printed and on the streets before 2:00 EST, with the giant headline “JFK SHOT” and the “news” that Johnson too was wounded.

As you, we sat for long unbroken hours watching the TV. From 7:00 in the morning until late in the evening for three uninterrupted days. Even my Republican husband was crying several times that dark weekend.

But as Montaigne wrote: “No one dies before his hour: the time you leave behind was no more yours than that which was lapsed and gone before you came into this world. Whenever your life ends, it is all there. The utility of living consists not in the length of days, but in the use of time.” Wherein I find some comfort.

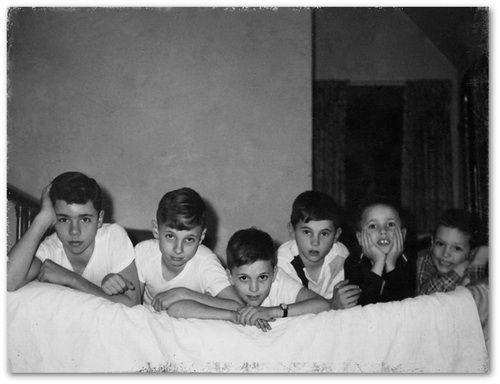

The six of us in our parents’ bedroom.

From left: Kip, Jeff, Chris, Dan, Luke, and Collin.

1963: Coldest Winter Since 1927.

– Rochester Post-Bulletin

We had no Nine Eleven to compare with Eleven Twenty-Two, but looking back similarities exist. The exact freeze-frame answer to the question “Where you were when you heard?”

The empty feeling the adults must have had when returning to work, picking up useless tools from wooden desks that no longer mattered really.

As my mother wrote, “There is too much and nothing to say.” The murder of JFK painted America black. Yet on the very day – November 22nd, 1963 – something good happened too, an ocean away. On that day, Parlophone Records released an album by a new “pop” group titled

With

The Beatles

. And on February 8th, 1964, the band flew to the U.S. on a Pan American jet to save the entire country.

It was Kip who brought home the Beatles’ first American album. I remember seeing the Capitol Records logo going around the spindle, that gristly hiss as the needle found the outside groove and then in the opening two seconds all six of our lives changed. Because there was Paul McCartney timing the opening of

I Saw Her Standing There

with his British num-bahs: “One, Two, Three, FAH!” and everything changed.

“Happiness, too, is inevitable,” wrote Camus and when Paul hit “FAH!” so it was. Happiness came as if from behind a cloud and shone on a nation wrapped in parkas and grief and suddenly it seemed okay, if just for a minute, to be happy again and that even Jackie might lift her black veil and smile at the sound.

In that One, Two, Three, FAH! we discovered a quality of being which would change us and remain with us the rest of our lives. We had discovered Cool and its name, The Beatles.

To fourth-graders with buck teeth (who looked like Ernie Douglas from

My Three Sons

) cool was something entirely new, surprisingly.

Sean Connery was cool playing Double-O Seven, yes; so was Spider-Man. They did cool things, had cool powers and gadgets. But that’s just it – they had and did cool; the Beatles

were

cool. They were the embodiment of cool; cool given flesh, cool that drew breath, told jokes, created music, and made entire stadiums full of girls go all wobbly.

The way they walked out on stage, the way they stood between sets on

The Ed Sullivan Show

, the cheek of their press conferences, their cigarettes at rakish angles. It was all so incredibly cool even Ernie Douglas’s like me were set to squealing in the sheer release of energy found in Cool. We’d never seen anything like it. The subtle rebellion of their tongue-in-cheek, their conspiratorial air, the ju-jitsu responses to questions from reporters with short haircuts – it all fascinated us as much the music.

Q: “What do you call your hair style?”

A: “Arthur.”

Q: “How did you find America?”

A: “Turn left at Greenland.”

Until now, the most sophisticated comedy we’d seen was what we now remember as “Dad Humor” – Dean Martin in Vegas making shitty, thinly veiled jokes about big boobs, or Sid Ceasar’s seltzer in the pants. Beatle wit appealed to our intelligence. With the right turn of phrase and a deadpan delivery we could laugh up our sleeves at the adult world. The Beatles were, above all else, cool.

The Beatles’ brand of coolness became our cosmology. Cool wasn’t binary, cool was quantum. You could be a little cool, kinda cool, or very cool. Each age bracket got you to a new level. In fact, discrete levels of coolness had been firmly delineated by the arbiter of cool, brother Jeff – in descending order it went: Studs, Aces, Princes, Sprinters, and Dolts.

Studs were Totally Cool. The Beatles were Studs; so was Steve McQueen. According to Jeff, a stud was “never perturbed by anything, never asks for help, and the fact that women can’t resist a Stud simply doesn’t occur to him.” Studs were so beyond cool they didn’t even

know

they were Studs.

Aces, on the other hand, knew they were Aces. Aces were cool guys but not the gods Studs were. Lucas McCain in the opening credits of

The Rifleman

– and the cool way he looked into the camera while reloading – was an Ace. The Beach Boys were also Aces, but only when they sang their fast songs. Though Jeff didn’t come out and say it, we little guys assumed Kip, Jeff, and their cool friend Chris Hallenbeck were all Aces.

A Prince, on the other hand, was a self-conscious Ace – “an Ace who smiled about it,” according to Chris Hallenbeck. A Prince could conceivably do something as cool as an Ace, but then laughed and looked up for approval while doing it. Dick Van Dyke or Soupy Sales, they were Princes. So was our brother Chris, who was too young to be an Ace and too old to be the next one down the list, a Sprinter.

I was a Sprinter. Irritating little kids pretending to be Spider-Man, running around the Millstone, stealing cigarettes, and air-strumming The Pagans’ guitars were Sprinters. Sprinters were just way too excited about everything. They were the wagging dog-tails of an Ace’s world, swinging wildly about and knocking stuff off the tables. Sprinters suffered from a syndrome known today as “Assumption of the First Person Plural;” a condition which made us tag along behind the Aces asking, “So, where are we goin’? What are we doin’?”

Bringing up the rear were Dolts. The only example of a Dolt Jeff ever provided was Hoss Cartwright from

Bonanza

. (You didn’t wanna be Hoss.)

Once we had seen the Beatles, being cool was all that mattered. The old icons were dead. JFK was gone. Elvis was in shitty Hawaiian movies. Even Paul Hornung, my halfback hero on the Green Bay Packers had fallen from grace (something about gambling that I never quite understood, but he was dethroned nonetheless).

Copying the Beatles was all that mattered and the easiest part to copy was the hairstyle. Dad didn’t allow us to let our hair get as long as the Beatles’. But we occasionally managed to grow our bangs down to our eyes and that was all the length we needed to perform the coolest move in the book – the “Hair Flip.” Brushing hair out of your eyes with your hands was for Sprinters. Cool guys simply

flicked

their head very quickly to the right – WHIP – preferably while saying something in a flat monotone that conveyed, “Everything that I have seen or heard since waking up at noon today has bored me.”

A monotone delivery of the wise-guy line was key to pulling off cool. Some of this ironic remove we learned from

A Hard Day’s Night

. Some we cribbed from old

Laurel & Hardy

movies.

Jeff perfected Laurel & Hardy’s deadpan humor with his best friend, Chris Hallenbeck. Chris was the son of the Mayo Clinic’s head of General Surgery, the man recruited to remove LBJ’s gall bladder (surgery made infamous by the

Life

magazine photo of the President showing his scar to startled reporters). Jeff and Hallenbeck would mimic the comics’ famous deadpan as they visited destructive pranks on each other. Hallenbeck would walk up to Jeff, rip the pocket off his shirt and quietly hand it back to him. Jeff would look up at Hallenbeck, blink, and rip

his

shirt pocket off. Throughout the exchange there would be no knowing smiles, no twinkles in the eye – just cold retribution. Hallenbeck took one of Jeff’s prized silver dollars, opened the window on the top floor of the Millstone and threw his coin far down into the weeds near the forest. Jeff, channeling Stan Laurel, obediently watched the dollar’s arc into oblivion. A pause. Without a word, he’d produce scissors and cut the laces to Hallenbeck’s shoes. Hallenbeck would sigh and walk silently back to this home down the road from the Millstone, carrying his shoes.

Even we little ones were learning the sublime joys of schadenfreude. At the stone barbecue pit down in the large half-acre of back yard we called the “Low Forty,” we enjoyed watching each other’s marshmallows catch fire and plop into the coals. To see your own treat browning to caramel perfection while your brother’s bubbled, blackened, and slid hissing into the flames was deeply satisfying.

This cheerful disrespect for anybody that wasn’t you, and anything that wasn’t yours, applied to everybody – including our dad. Jeff remembers sitting on the back porch with Kip on a hot day in the summer of ’63, drinking iced tea. As they cooled their heels they could hear their hard-working father grudgingly mow the lawn in a distant part of the yard. The sleepy drone of the motor came to metallic hacking end as Dad ran over one of his own workshop tools, carelessly abandoned there in the tall grass by one of his sons.

At the report of this sound, Kip and Jeff began laughing into the straws of their iced tea, producing bubbles.

To hear your father run the lawn mower over one of his own tools was – in my family anyway – hilarious. Had we been standing right next to my father when it happened, it wouldn’t have been as funny. But heard from a distance you could interpret an entire story in one hot-summer metal-on-metal sound – how one of the father’s prized workbench tools was borrowed without permission, left to rust in the rain, concealed by growing grass, and then ruined by his own hand, even as he dulled the mower’s blades. It was funny not just because we were all angry at Dad. It was more the graceful economy of its symbolism packed into one CLANG of finality. A sound of somebody “losing,” of somebody being further behind than they were a minute ago, reduced in some way. It was classic victim comedy.

* * *

Watching the Beatles in

A Hard Day’s Night

gave us the idea of making our own funny movies. They were all victim comedies and we called them “The Ridiculous Films.” They were shot with an old 8mm movie camera that Dad had given up on and if they had a theme it was “Sprinters Getting Killed.”

Their structure was classic.

We open on our protagonist, a fourth-grader with buck teeth strolling along in front of the Millstone. In Act II, the antagonist is introduced with swift and economic story telling – brother Jeff comes around the corner with a baseball bat and beats the shit out of me. (A pillow hidden in the victim’s coat allows for the delivery of many cinematically robust and satisfying blows.)

The fourth-grader collapses on the driveway.

Had the film ended here critics might have rightly argued the work lacked finality; that the entire piece was ambiguous and left the audience asking, “What, ultimately, happened here?” But Act III ties up the storylines in a tidy denouement. Thanks to a cleverly wardrobed body double, when the camera rolls again we see Jeff driving Dad’s car over the crumpled form of the Sprinter. Fade to black. (Cut, actually; there’s no fading with a Brownie movie camera.)

Audience test scores were off the chart. Squeals of delight filled the living room when the little 50-foot reel premiered on Dad’s projector. “More blood,” demanded the audience and a sequel was released the following month (after we talked Mom into getting us a new roll of film).

What might now be called “Dead Sprinters II” built on the original’s success and used the same opening: fourth-grader stands in front of Millstone. But this time it is brother Dan who enters screen right, grabs the victim and throws him into the house through the open door. The camera, still running, pans seamlessly up to third-story window where a stuffed body double suffers the indignities of defenestration and thuds on the pavement below.

Where’s this going? a savvy audience might ask. Will the narrative clarify the victim’s back-story? Who

is

he, really? What issues in his past led him to this development? Act III, while answering none of these questions does address the test audience’s earlier suggestion for “more blood.” A crowd encircles the protagonist, now lying unconscious on the concrete. They’re lining up to pay Dan a quarter. But for what, dammit, what?

It’s the rental fee for the baseball bat, making its second appearance in the Ridiculous Films. As the curtain falls on Act III, the brothers pound the bejesus out of me.

* * *

“It’s all so very easy to laugh at oneself. What we must learn to do is to laugh at others.”

So said comedy writer Michael O’Donohue and this ability to look down on others was held in high regard by the six brothers.

Living directly to the south of us was a little boy, Jeffrey Hartman, five-and-a-half years old. Jeffrey was not only a Sprinter, he was a Momma’s boy. Almost all of his short visits to our yard ended within minutes of his arrival with the shriek of Mrs. Hartman calling him back home.