Think Like an Egyptian (9 page)

Read Think Like an Egyptian Online

Authors: Barry Kemp

The Egyptians grew their main crops (wheat, barley, and flax for linen) in fields of sometimes irregular shape. (An ancient manual explains how to measure the areas of fields, which could be rectangular, circular, triangular, or trapezoidal in shape. The given examples measure between 0.8 and 2.5 hectares.) When they grew lesser crops (vegetables and spices), however, Egyptians worked the land differently. We know from ancient pictures and from actual examples found by archaeologists that they laid out flat beds consisting of grids of square plots separated by carefully made ridges of mud. The sides of each plot measured about 53 centimeters, the length of an Egyptian cubit. They then filled each plot with prepared soil in which the crops would be grown. When they counted up the plots, the area of soil under cultivation was immediately given. Whether the grid that is the basis of the

hieroglyph represents these gridded beds or is a simplification of the division of the land into more irregular fields is hard to judge.

hieroglyph represents these gridded beds or is a simplification of the division of the land into more irregular fields is hard to judge.

hieroglyph represents these gridded beds or is a simplification of the division of the land into more irregular fields is hard to judge.

hieroglyph represents these gridded beds or is a simplification of the division of the land into more irregular fields is hard to judge.The ancient nomes, far smaller than Egypt’s modern provinces, were home to families of wealth and local authority, who delighted in ostentatious displays that sometimes seemed to be a direct challenge to the king. In his tomb at Deir el-Bersheh, the governor Djehutyhetep recorded a moment when a host of his men dragged a huge alabaster statue of himself, 6.8 meters tall, from the quarry to a crossing place on the Nile and onward to what seems to have been his palace in the city of Hermopolis. His neighbors downstream, their tombs at Beni Hasan, maintained their own private army and were also made responsible, by the king, for a huge tract of the eastern desert. Farther south, at Qau, the family of local governors built huge tombs with halls cut into the rock, terraced temples in front, and long processional causeways down to the edge of the fields. Nonetheless, they had to balance their own self-interest against loyalty to their king, and included in their tombs long texts expressing their fidelity.

When royal power grew weak, local governors were the ones who stood to gain most, and sometimes they even seized by force the nomes and cities of their neighbors. Ankhtyfy, a governor to the south of Thebes during a time of civil war (c. 2150 BC, early in the 1st Intermediate Period), seized the nome of his neighbor at Edfu but then faced attacks from Thebes, his own northern neighbor, whose ruling family went on to take over the whole country and become the next line of kings.

When during the four centuries of the Late Period (8th-4th centuries BC) the country had to accept long periods of foreign rule, it was the local governors who acted as a bridge, choosing to serve the alien rulers and so maintain order and prosperity in their area. In his annals of conquest the Assyrian king Assurbanipal lists the names of 20 of them, the last being a man well known from his statues and from his huge tomb at Luxor, Menthuemhat, the mayor of Thebes. Menthuemhat lived on through further changes of rule and became a major organizer of temple repairs. The priest of Sais, Udjahor-resenet, who worked closely with the Persian conquerors to secure benefits to his own temple in the 6th century BC, is another example.

How should we judge such men? Behavior of this kind attracts liberal criticism in the modern world: we might expect true patriots to fight the foreign occupier. Some Egyptians, especially those who lived in the south of the country, did draw the line between themselves and foreigners, and rose in revolt on several occasions in the last centuries of Egyptian civilization. By this time, however, the resident population of Egypt included a large element of “foreigners” who probably had limited regard for traditional Egyptian culture. It might have seemed more sensible to men like Menthuemhat and Udjahor-resenet to cooperate with their foreign masters in order to preserve what remained of the old culture.

14.

STELA (STANDING BLOCK OR SLAB OF STONE)

The sign depicts a round-topped slab of stone on a narrow pedestal. Egyptians loved to commemorate their lives for posterity, and stelae were used to record particular acts of piety or the history of one’s life or one’s outstanding personal qualities, and to list the offerings that one hoped to receive for ever more. We know the names and careers of ancient Egyptians mainly from the many thousands of stelae that have survived.

Stelae were also used to mark boundaries. Ownership of agricultural land was the basis of power and wealth in ancient Egypt. Egyptians were precise about their territory, and the boundaries of fields, cities, and provinces were often permanently delineated. One of the provincial governors, Khnumhetep II of the 12th Dynasty, recorded in his tomb at Beni Hasan how the king confirmed his governorship of the area, “having established for me a southern boundary stela and having set up a northern one like heaven, and having divided the Nile down its middle.” This was part of a wider scheme of King Amenemhat II’s to reestablish “whatever he found in disarray and [return] whatever a city had taken from its neighbor, causing city to know its boundary with city [so that] their boundary stelae were established like heaven and their river frontage known according to what was in the writings.”

The only boundary stelae to have survived in Egypt are carved into the cliffs on both sides of the Nile around King Akhenaten’s new city of Tell el-Amarna. They are inscribed with a sacred oath declaring that the city will never extend beyond their limits. So important were the stelae to Akhenaten that a year after the first set was carved a second set was added, and then two years after this the king visited them, in his chariot, to repeat the oath.

It became the duty of kings to “enlarge the boundaries of Egypt” through conquest. Around 1862 BC King Senusret III set up a boundary stela beside the river in Nubia, 350 kilometers to the south of the Egyptian frontier at Aswan, at a place called Semna. It stated: “Any son of mine who maintains this boundary that My Majesty has made, he is a son of mine who was born to My Majesty ... He who shall abandon it and not fight for it is indeed no son of mine.” The king set up a statue of himself at the boundary, ”that you might be inspired by it and fight on its behalf.” Three centuries later, in the New Kingdom, the southern boundary stood at more than twice the distance to the south, the result of the renewed Egyptian policy of aggression. On an isolated rock near Kurgus in what is now Sudan, King Tuthmosis I had a scene and a text carved to act as his boundary marker. Tuthmosis III subsequently added a similar one. Yet the Egyptian empire, especially in Palestine and Syria, remained fragile, and the Egyptians often found themselves fighting over territory across which many of their predecessors had already marched.

15.

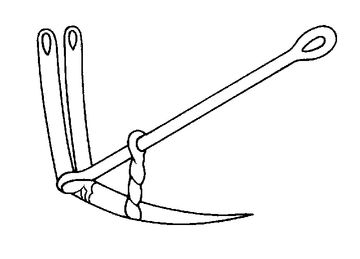

PLOUGH

The plough was a Near Eastern invention of the prehistoric periods and is one of the very few truly labor-saving devices that the Egyptians adopted. The wealth and success of ancient Egypt depended to a large extent on the cereal agriculture of the Nile floodplain. The fertile soil and the annual autumn flooding of the land, and its careful management by means of earthen banks and drainage ditches, gave the expectation of abundant harvests. In modern times the damming of the river has allowed farming around the year. Neither the land nor the farmer gets a natural break—whereas in ancient times farming ran through a single annual cycle that began with the inundation, followed by ploughing, planting, and growing, and ending with the harvest and a lengthy period when the land rested. It is now assumed that it was at this relatively slack time that kings would send out demands for extra labor for great building projects, especially the dragging of stone for pyramids.

One Egyptian concept of the afterlife gave it an agricultural setting, the Field of Iaru, with dead members of the official class facing an eternity of agricultural labor—something that they would have ardently sought to avoid in life. The tomb of the craftsman Sennedjem (c. 1250 BC), for example, shows both him and his wife (in immaculate white garments) ploughing and harvesting. Sennedjem lived at a time when ideas on the relationship between earthly existence and eternity were changing. In earlier periods, the art on tomb walls celebrated the life of landed gentry, set ambiguously in time, implying that this was also the life to come. There was little room left for pictures of gods or halls of judgment. By Sennedjem’s time, however, gods had largely crowded out the scenes of eternity as one long holiday. For the next thousand years, until ancient Egyptian culture faded away, tomb art avoided images of earthly pleasures and sought instead to safeguard the dead against unpredictable spiritual forces. Household or personal goods were no longer buried in the tomb. What remained were amulets and a copy of the Book of the Dead—a set of 189 spells or chapters written on a continuous roll of papyrus, a license to an eternal place among the gods and demons of the afterlife.

Even in earlier periods, however, behind the cheerful materialism of the tomb scenes, there lay a fear of labor conscription. The king and the various departments of his administration had the right to command people to carry out work such as soldiering or building a pyramid. Egyptians feared that conscription might reappear in the afterlife. Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead is a spell first encountered around 2000 BC and was in use to the end of Egyptian civilization. It was a spell of substitution. When called upon to do so, a manufactured figurine would stand in for the deceased person when the summons for conscription arrived. Who, in the next world, would issue that summons is never stated. Even kings faced the same fate. It was evidently a visceral dread that tells us something very important about the quality of life in ancient Egypt. You never knew when your name would appear on a list, even though you might be one of the elite.

The figurines, called shabti or

ushabti

by the Egyptians, were laid in the tomb. Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead was often written on them, and they are shown with a hoe and a basket for carrying lumps of earth. These symbolized field labor of the most basic kind. The numbers of

ushabti-

figures multiplied during the later New Kingdom and afterward. The ideal was a

ushabti

for every day of the year, and a complement of overseer figures (who carry a whip) to look after the

ushabti

-figures in gangs of 10, making a set of 365

ushabti

-figures and 36 overseers—401 in total. A papyrus receipt has survived for just such a set of 401 figures, sold for silver to a priest by the “chief maker of amulets of the temple of Amun.” It is likely that the temple would receive a portion of the payment, if not all, illustrating that organized religion in ancient Egypt relied in large part upon conventional economic transactions.

ushabti

by the Egyptians, were laid in the tomb. Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead was often written on them, and they are shown with a hoe and a basket for carrying lumps of earth. These symbolized field labor of the most basic kind. The numbers of

ushabti-

figures multiplied during the later New Kingdom and afterward. The ideal was a

ushabti

for every day of the year, and a complement of overseer figures (who carry a whip) to look after the

ushabti

-figures in gangs of 10, making a set of 365

ushabti

-figures and 36 overseers—401 in total. A papyrus receipt has survived for just such a set of 401 figures, sold for silver to a priest by the “chief maker of amulets of the temple of Amun.” It is likely that the temple would receive a portion of the payment, if not all, illustrating that organized religion in ancient Egypt relied in large part upon conventional economic transactions.

Other books

Wave of Memories: The Sons of the Zodiac by Addison Fox

Under the Surface by Katrina Penaflor

Haunted in Death by J. D. Robb

The Fugitive by Pittacus Lore

Ruined by a Rake by Erin Knightley

Rosie O'Dell by Bill Rowe

Devil's Bargain by Jade Lee

Spies Against Armageddon by Dan Raviv

The Same Sky by Amanda Eyre Ward

The Publicist Book One and Two by George, Christina