Think Like an Egyptian (4 page)

Read Think Like an Egyptian Online

Authors: Barry Kemp

Today the delta, the north, is the more prosperous part of Egypt, and those who live there and who are naturally more exposed to the cultures of the Mediterranean and of the lands to the northeast tend to see the people who live south of Cairo as rough and provincial. It may not always have been so. For the first half of its ancient history, between approximately 3000 and 1300 BC, the ruling families of kings came from the south. Their main city, Thebes, served as the ceremonial center for the whole country. During the third main historical era (the New Kingdom) it was here that kings were buried (in the Valley of Kings), even when, during the later years, they were men from the north. Thebes was not, though, the equivalent of a modern capital. The main royal residence, Memphis, where government was centered, remained in the north, closer to the delta. One ancient source described it as “ ‘the balance of the two lands’ in which Upper and Lower Egypt had been weighed.”

2.

DESERT

The desert for most Egyptians was a crust of coarse sand and pebbles over horizontal layers of limestone or sandstone. Only those who ventured far to the west—to the area of the Kharga oasis—would have seen the desert of our popular imagination, a sea of sand dunes. Over huge areas, especially to the east of the Nile, the flow from torrential rains has cut the desert surface into networks of valleys, often with precipitous sides: they are nowadays named after the word “wadi,” originally an Arabic term, meaning a valley, that is dry except in the rainy season. Further still to the east, much harder rocks rise up into jagged hills and low mountains that extend to the Red Sea.

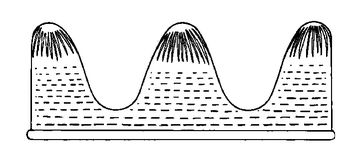

The hieroglyph for desert depicts a broken landscape, with three rounded hills separated by deep valleys. It was added as a determinative sign to words for distant places beyond the Egyptian borders, such as “east” and “west,” and for “valley” and “cemetery”—cemeteries often lay on the desert margin (see no. 36, “Cemetery”).

The word

3st

3st

(

khaset

) denoted desert, hill country, and foreign land, all at once. In time it took on an ominous quality, especially when applied to the lands to the northeast. These were home to rulers whose ambitions matched those of Egyptian kings and who, from time to time, saw Egypt as an enticing target for their own conquests. In the 17th century BC, the “rulers of foreign lands,” from a homeland in Palestine, became the “foreign rulers” of Egypt. This line of kings, called the Hyksos, ruled for two centuries until challenged by a revolt started at Thebes, which had been reduced to a minor-state capital with its own line of kings. Under King Kamose the revolt became a civil war, eventually resulting in the expulsion of the hated “Asiatics,” as the foreign rulers and their people were also called. This event marked the beginning of the New Kingdom.

3st

3st(

khaset

) denoted desert, hill country, and foreign land, all at once. In time it took on an ominous quality, especially when applied to the lands to the northeast. These were home to rulers whose ambitions matched those of Egyptian kings and who, from time to time, saw Egypt as an enticing target for their own conquests. In the 17th century BC, the “rulers of foreign lands,” from a homeland in Palestine, became the “foreign rulers” of Egypt. This line of kings, called the Hyksos, ruled for two centuries until challenged by a revolt started at Thebes, which had been reduced to a minor-state capital with its own line of kings. Under King Kamose the revolt became a civil war, eventually resulting in the expulsion of the hated “Asiatics,” as the foreign rulers and their people were also called. This event marked the beginning of the New Kingdom.

In another Egyptian defeat around 525 BC, toward the end of Egyptian civilization, the Persian King Cambyses took control of the country. He was described as “the great prince of all the foreign lands” by one of his leading Egyptian collaborators, a priest named Udjahor-resenet, who realized that only by transferring his loyalty would his temple and its traditional cults survive and prosper. Udjahor-resenet served for a time, perhaps as a physician, in the Persian court in the land of Elam (probably in the city of Susa), in the part of the Mesopotamian plain that lies in modern Iran. His plan succeeded. He returned to Egypt with a commission to reendow the center of learning (which the Egyptians called the “House of Life,” see no. 82, “Scribal kit”), attached to his beloved temple.

The mind-set of Egyptians was strongly influenced by the hostile, mountainous, foreign lands that surrounded them. It was a duty of kings to conquer threatening enemies, who were named in lists on the outside walls of temples. To the title of each enemy land was added the “desert” hieroglyph, even if they were not desert places. These included places in Syria, Babylonia (which was flat and fertile and too far from Egypt to be conquered) and Crete (which was mountainous and was also never conquered by Egypt). In their claims to conquest, the lists contained an element of wishful thinking.

3.

GRAIN (OF SAND)

The hieroglyph for “land” is often accompanied by the sign for a grain, a tiny circle. This is either repeated three times ··· or shown once with three small vertical strokes added

, to indicate that there are normally many. Signs of this kind, examples of determinatives, are added to the basically phonetic hieroglyphs that spelled nouns and verbs, in order to point to a broader family to which an individual word belongs. From signs of this kind we can learn how Egyptians grouped and classified their world, even though they appear not to have given much conscious thought to systems of classification.

, to indicate that there are normally many. Signs of this kind, examples of determinatives, are added to the basically phonetic hieroglyphs that spelled nouns and verbs, in order to point to a broader family to which an individual word belongs. From signs of this kind we can learn how Egyptians grouped and classified their world, even though they appear not to have given much conscious thought to systems of classification.

, to indicate that there are normally many. Signs of this kind, examples of determinatives, are added to the basically phonetic hieroglyphs that spelled nouns and verbs, in order to point to a broader family to which an individual word belongs. From signs of this kind we can learn how Egyptians grouped and classified their world, even though they appear not to have given much conscious thought to systems of classification.

, to indicate that there are normally many. Signs of this kind, examples of determinatives, are added to the basically phonetic hieroglyphs that spelled nouns and verbs, in order to point to a broader family to which an individual word belongs. From signs of this kind we can learn how Egyptians grouped and classified their world, even though they appear not to have given much conscious thought to systems of classification.“Land” is granular, as is “sand” when found in the desert and in the riverbank (though not “mud,” which takes a different determinative,

, linking it to irrigation canals). Equally granular is “salt,” which also occurs widely in the desert, almost like a variant of sand. “Natron,” a salty lake deposit, is part of the same family. Its principal source is the Wadi Natrun, an area of dried lakebeds in the western desert. It is a natural drying agent, absorbing moisture. It was the key ingredient in the making of mummies, a process of thoroughly drying out human or animal tissue, achieved by heaping natron over the corpse (see no. 38, “Mummy”). Natron was also an agent of purification. It was sprinkled on the ground in sacred buildings, and it was drunk in solution to cleanse priests before they entered a period of service in the temple. Charges were brought against one priest of Elephantine who entered upon his temple duties after only seven of his ten days of purification. His punishment is not recorded.

, linking it to irrigation canals). Equally granular is “salt,” which also occurs widely in the desert, almost like a variant of sand. “Natron,” a salty lake deposit, is part of the same family. Its principal source is the Wadi Natrun, an area of dried lakebeds in the western desert. It is a natural drying agent, absorbing moisture. It was the key ingredient in the making of mummies, a process of thoroughly drying out human or animal tissue, achieved by heaping natron over the corpse (see no. 38, “Mummy”). Natron was also an agent of purification. It was sprinkled on the ground in sacred buildings, and it was drunk in solution to cleanse priests before they entered a period of service in the temple. Charges were brought against one priest of Elephantine who entered upon his temple duties after only seven of his ten days of purification. His punishment is not recorded.

, linking it to irrigation canals). Equally granular is “salt,” which also occurs widely in the desert, almost like a variant of sand. “Natron,” a salty lake deposit, is part of the same family. Its principal source is the Wadi Natrun, an area of dried lakebeds in the western desert. It is a natural drying agent, absorbing moisture. It was the key ingredient in the making of mummies, a process of thoroughly drying out human or animal tissue, achieved by heaping natron over the corpse (see no. 38, “Mummy”). Natron was also an agent of purification. It was sprinkled on the ground in sacred buildings, and it was drunk in solution to cleanse priests before they entered a period of service in the temple. Charges were brought against one priest of Elephantine who entered upon his temple duties after only seven of his ten days of purification. His punishment is not recorded.

, linking it to irrigation canals). Equally granular is “salt,” which also occurs widely in the desert, almost like a variant of sand. “Natron,” a salty lake deposit, is part of the same family. Its principal source is the Wadi Natrun, an area of dried lakebeds in the western desert. It is a natural drying agent, absorbing moisture. It was the key ingredient in the making of mummies, a process of thoroughly drying out human or animal tissue, achieved by heaping natron over the corpse (see no. 38, “Mummy”). Natron was also an agent of purification. It was sprinkled on the ground in sacred buildings, and it was drunk in solution to cleanse priests before they entered a period of service in the temple. Charges were brought against one priest of Elephantine who entered upon his temple duties after only seven of his ten days of purification. His punishment is not recorded.The desert produced other valued minerals and precious stones grouped in the same general category, which extended from the granular to the pebbly. “Amethyst” and “turquoise” are two. A third is “eye paint,” or kohl—in the historic periods this was usually finely ground gray galena (lead sulphide), probably mixed with water (or water and gum) to make a paste. The green mineral “malachite,” the principal ore of copper, and the metallic “copper” derived from it by smelting both use ··· as their determinative, as do words for metals generally, for example “gold” (see no. 87), “silver,” “bronze” (see no. 88), and “iron.” Here the original earthy mineral nature of the substance has been remembered despite the fact that the finished appearance of metal is hard, often shiny, and definitely nongranular.

The granular sign ··· also extends to cover plant material. Our identification of Egyptian names for plants, known primarily from medical texts, is frequently uncertain. But when plant elements use ··· as a determinative, it is likely that seeds or fruits are being referred to, such as long beans, sesame seed, lentils, and chickpeas, all staples of the Egyptian diet. Another important ingredient of Egyptian life was incense, the aromatic resin from, among others, myrrh, frankincense, and pistacia trees—this takes the same determinative because the Egyptians normally used it in pellet form to burn in their temples and homes. One granular group keeps its own sign, ···. This is used as a determinative for the several varieties of grain that the Egyptians recognized, including barley, Upper Egyptian barley, and emmer wheat. A common variant for cereals is

, a measuring vessel with grains pouring out. Cereal grain was the subject of an administrative system so huge that it formed a separate category in the experience of life.

, a measuring vessel with grains pouring out. Cereal grain was the subject of an administrative system so huge that it formed a separate category in the experience of life.

, a measuring vessel with grains pouring out. Cereal grain was the subject of an administrative system so huge that it formed a separate category in the experience of life.

, a measuring vessel with grains pouring out. Cereal grain was the subject of an administrative system so huge that it formed a separate category in the experience of life.Other books

Flight to Canada by Ishmael Reed

Disquiet at Albany by N. M. Scott

After Dark by Phillip Margolin

Statistics Essentials For Dummies by Rumsey, Deborah

Sara Paretsky - V.I. Warshawski 10 by Total Recall

Vulture's Gate by Kirsty Murray

Arcadia by Jim Crace

The God Mars Book Four: Live Blades by Michael Rizzo

Wicked Reunion (Wicked White Series Book 2) by Michelle A. Valentine

The_Amazing_Mr._Howard by Kenneth W. Harmon