Theory of Fun for Game Design (6 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

Either way, I have an answer for my late grandfather, and it looks like what I do fits right alongside the upstanding professions of my various aunts and uncles. Fireman, carpenter, and… teacher.

Formal training isn’t really required to become a game designer. Most of the game designers working professionally today are self-taught. That is changing rapidly as university programs for game designers crop up all around the country and the world.

I went to school to be a writer, mostly. I believe really passionately in the importance of writing and the incredible power of fiction. We learn through stories; we become who we are through stories.

My thinking about what fun is led me to similar conclusions about games. I can’t deny, however, that stories and games teach really different things. Games don’t usually have a moral. They don’t have a theme in the sense that a novel has a theme.

The population that uses games most effectively is the young. Certainly folks in every generation keep playing games into old age (pinochle, anyone?), but as we get older we view them more as the exception. Games are viewed as frivolity. In the Bible in 1 Corinthians, we are told, “When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child; when I became a man, I gave up childish ways.” But children speak honestly—sometimes too much so. Their reasoning is far from impaired—it is simply inexperienced. We assume that games are childish ways, but is that really so?

We don’t actually put away the notion of “having fun,” near as I can tell. We migrate it into other contexts. Many claim that work is fun, for example (me included). Just getting together with friends can be enough to give us the little burst of endorphins we crave.

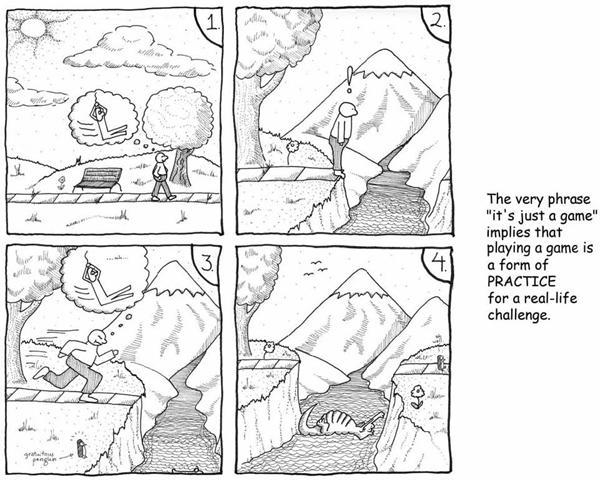

We also don’t put aside the notion of constructing abstract models of reality in order to practice with them. We practice our speeches in front of mirrors, run fire drills, go through training programs, and role-play in therapy sessions. There are games all around us. We just don’t call them that.

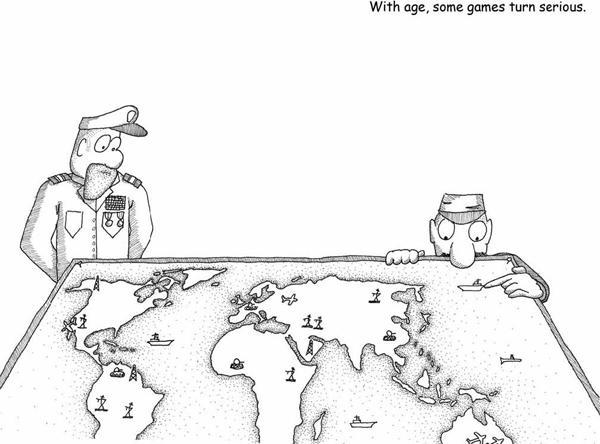

As we age, we think that things are more serious and that we must leave frivolous things behind. Is that a value judgment on games or is it a value judgment on the content of a given game? Do we avoid the notion of fun because we view the content of the fire drill as being of greater import?

Most importantly—would fire drills be more effective if they were fun activities?

If games are essentially models of reality, then the things that games teach us must reflect on reality.

My first thought was that games are models of hypothetical realities since they often bear no resemblance to any reality I know.

As I looked deeper, though, I found that even whacked-out abstract games do reflect underlying reality. The guys who told me these games were all about vertices were correct. Since formal rule sets are basically mathematical constructs, they always end up reflecting forms of mathematical truth, at the very least. (Formal rule sets are the basis for most games, but not all—there are classes of games with informal rule sets, but you can bet that the little girls will cry “no fair” when someone violates an unstated assumption in their tea party.)

Sadly, reflecting mathematical structures is also the only thing many games do.

The real-life challenges that games prepare us for are almost exclusively ones based on the calculation of odds. They teach us how to predict events. A huge number of games simulate forms of combat. Even games ostensibly about building are usually framed competitively.

Given that we’re basically hierarchical and strongly tribal primates, it’s not surprising that most of the basic lessons we are taught by our early childhood play are about power and status. Think about how important these lessons still are within society, regardless of your particular culture. Games almost always teach us tools for being the top monkey.

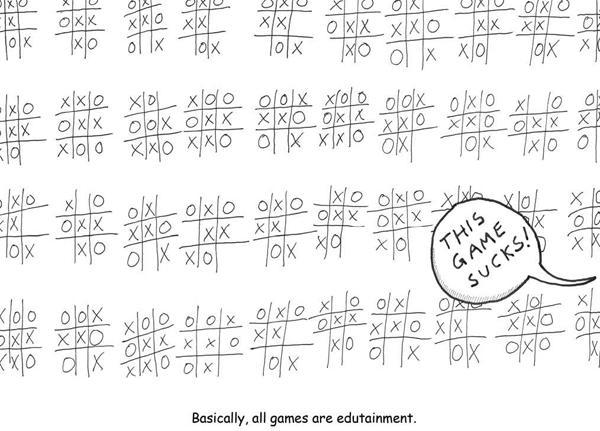

Games also teach us how to examine the environment, or space, around us. From games where we fit together odd shapes to games where we learn to see the invisible lines of power projection across a grid, much effort is spent in teaching us about territory. That is what tic-tac-toe is essentially all about.

Spatial relationships are, of course, critically important to us. Some animals might be able to navigate the world using the Earth’s magnetic field, but not us. Instead, we use maps and we use them to map all sorts of things, not just space. Learning to interpret symbols on a map, assess distance, assess risk, and remember caches must have been a critically important survival skill when we were nomadic tribesmen. But we also map things like temperature. We map social relationships (as graphs of edges and vertices, in fact). We map things over time.

Examining space also fits into our nature as toolmakers. We learn how things fit together. We often abstract this a lot—we play games where things fit together not only physically, but conceptually as well. By playing games of classification and taxonomy, we extend mental maps of relationships between objects. With these maps, we can extrapolate behaviors of these objects.

Most games incorporate some element of spatial reasoning. The space may be a Cartesian coordinate space, or it may be a directed conceptual graph, but it’s all the same thing in the end (as a mathematician will tell you). Classifying, collating, and exercising power over the contents of a space is one of the fundamental lessons of all kinds of gameplay.

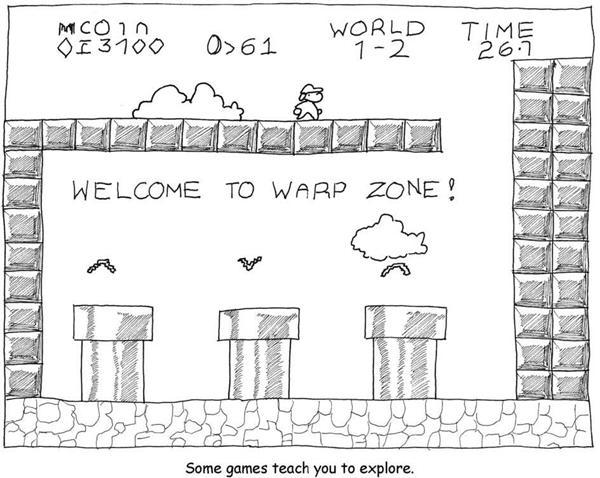

Exploring conceptual spaces is critical to our success in life. Merely understanding a space and how the rules make it work isn’t enough, though. We also need to understand how it will react to change to exercise power over it. This is why games progress over time. There are no games that take just one turn.

Let’s consider so-called “games of chance” that use a six-sided die. Here we have a possibility space—values labeled 1 through 6. If you roll dice against someone, the game you are playing might seem to end very quickly. You also might feel you don’t have much control over the outcome. You might think an activity like this shouldn’t be called a game. It certainly seems like a game you can play in one turn.

But I suggest gambling games like this are actually designed to teach us about odds. You don’t just play for one turn, and with each turn you try to learn more about how odds work. (Unfortunately, you prove you didn’t learn the lesson—especially if you are gambling for money.) We know from experiments that probability is something our brains have serious trouble grasping.

Exploring a possibility space is the only way to learn about it. Most games repeatedly throw evolving spaces at you so that you can explore the recurrence of symbols within them. A modern video game will give you tools to navigate a complicated space, and when you finish, the game will give you another space, and another, and another.

Some of the really important parts of exploration involve memory. A huge number of games involve recalling and managing very long and complex chains of information. (Think about counting cards in blackjack or playing competitive dominoes.) Many games involve thoroughly exploring the possibility space as part of their victory condition.

In the end, most games have something to do with power. Even the innocuous games of childhood tend to have violence lurking in their heart of hearts. Playing “house” is about jockeying for social status. It is richly multileveled, as kids position themselves in authority or not over other kids. They play-act at using the authority that their parents exercise over them. (There’s this idealized picture of girls as being all sweetness and light, but there are few more viciously status-driven groups on earth.)

Consider the games that get all the attention lately: shooters, fighting games, and war games. They are not subtle about their love of power. The gap between playing these games and cops and robbers is small as far as the players are concerned. They are all about reaction times, tactical awareness, assessing the weaknesses of an opponent, and judging when to strike. Just as my playing guitar was in fact preparing me for playing mandolin by teaching me skills beyond basic guitar fretting, these games teach many skills that are relevant in a corporate setting. We pay attention to the obvious nature of a particular game and we miss the subtler point; be it cops and robbers or

CounterStrike

, the real lessons are about team-work and not about aiming.