Theory of Fun for Game Design (3 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

There’s a field called “game theory,” which has something to do with games, a lot to do with psychology, even more to do with math, and not a lot to do with game design. Game theory is about how competitors make optimal choices, and it’s mostly used in politics and economics, where it is frequently proven wrong.

Looking up “game” in the dictionary isn’t that helpful. Once you leave out the definitions referring to hunting, they wander all over the place. Pastimes or amusements are lumped in with contests. Interestingly, none of the definitions tend to assume that fun is a requirement: amusement or entertainment at best is required.

Those few academics who tried to define “game” have offered up everything from Roger Caillois’s “activity which is…voluntary…uncertain, unproductive, governed by rules, make-believe” to Johan Huizinga’s “free activity…outside ‘ordinary’ life…” to Jesper Juul’s more contemporary and precise take: “A game is a rule-based formal system with a variable and quantifiable outcome, where different outcomes are assigned different values, the player exerts effort in order to influence the outcome, the player feels attached to the outcome, and the consequences of the activity are optional and negotiable.”

None of these help designers find “fun,” though.

Game designers themselves offer a bewildering and often contradictory set of definitions.

- To Chris Crawford, outspoken designer and theorist, games are a subset of entertainment limited to conflicts in which players work to foil each other’s goals, just one of many leaves off a tree that includes playthings, toys, challenges, stories, competitions, and a lot more.

- Sid Meier, designer of the classic

Civilization

computer games, gave a classic definition of “a series of meaningful choices.” - Ernest Adams and Andrew Rollings, authors of

Andrew Rollings and Ernest Adams on Game Design

, narrow this further to “one or more causally linked series of challenges in a simulated environment.” - Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman say in their book

Rules of Play

that a game is “a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome.”

This feels like a quick way to get sucked into quibbling over the classification of individual games. Many simple things can be made complex when you dig into them, but having fun is something so fundamental that surely we can find a more basic concept?

I found my answer in reading about how the brain works. Based on my reading, the human brain is mostly a voracious consumer of patterns, a soft pudgy gray Pac-Man of concepts. Games are just exceptionally tasty patterns to eat up.

When you watch a kid learn, you see there’s a recognizable pattern to what they do. They give it a try once—it seems that a kid can’t learn by being taught. They have to make mistakes themselves. They push at boundaries to test them and see how far they will bend. They watch the same video over and over and over and over and over and over…

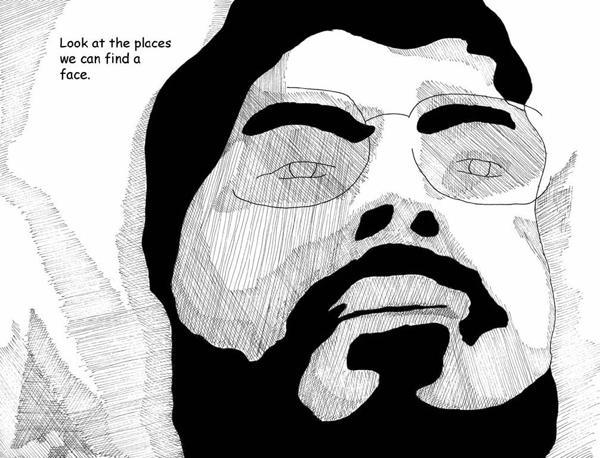

Seeing patterns in how kids learn is evidence of how pattern-driven our brains are. We pattern-seek the process of pattern-seeking! Faces may be the best example. How many times have you seen faces in wood grain, in the patterns in plaster walls, or in the smudges on the sidewalk? A surprisingly large part of the human brain is devoted to seeing faces—when we look at a person’s face, a huge amount of brainpower is expended in interpreting it. When we’re not looking at someone face-to-face, we often misinterpret what they mean because we lack all the information.

The brain is hardwired for facial recognition, just as it is hardwired for language, because faces are incredibly important to how human society works. The capability to see a face in a collection of cartoony lines and interpret remarkably subtle emotions from them is indicative of what the brain does best.

Simply put, the brain is made to fill in blanks. We do this so much we don’t even realize we’re doing it.

Experts have been telling us for a while now that we’re not really “conscious” in the way that we think we are; we do most things on autopilot. But autopilot only works when we have a reasonably accurate picture of the world around us. Our noses really ought to be blocking a lot of our view, but when we cross our eyes, our brains have magically made our nose invisible. What the heck has the brain managed to put in its place? The answer, oddly, is an

assumption

—a reasonable construct based on the input from both eyes and what we have seen before.

Assumptions are what the brain is best at. Some days, I suspect that makes us despair.

There’s a whole branch of science dedicated to figuring out how the brain knows what it does. It’s already led to a wonderful set of discoveries.

We’ve learned that if you show someone a movie with a lot of jugglers in it and tell them in advance to count the jugglers, they will probably miss the large pink gorilla in the background, even though it’s a somewhat noticeable object.

The brain is good at cutting out the irrelevant

.

We’ve also found that if you get someone into a hypnotic trance and ask them to describe something, they will often describe much more than if they were asked on the street.

The brain notices a lot more than we think it does

.

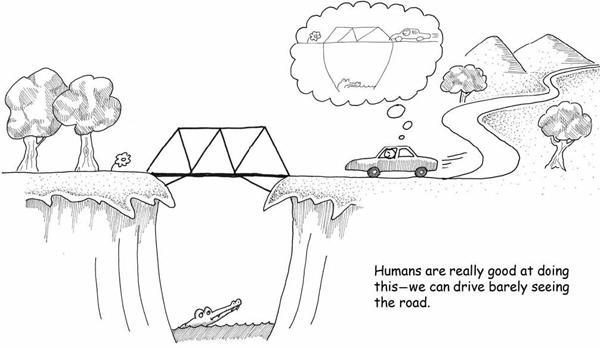

We now know that when you ask someone to draw something, they are far more likely to draw the generalized iconic version of the object that they keep in their head than they are to draw the actual object in front of them. In fact, seeing what is actually there with our conscious mind is really hard to do, and most people never learn how to do it!

The brain is actively hiding the real world from us

.

These things fall under the rubric of “cognitive theory,” a fancy way of saying “how we think we know what we think we know.” Most of them are examples of a concept called “chunking.”

Chunking is something we do all the time.

If I asked you to describe how you got to work in the morning in some detail, you’d list off getting up, stumbling to the bathroom, taking a shower, getting dressed, eating breakfast, leaving the house, and driving to your place of employment. That seems like a good list, until I ask you to walk through exactly how you perform just one of those steps. Consider the step of getting dressed. You’d probably have trouble remembering all the stages. Which do you grab first, tops or bottoms? Do you keep your socks in the top or second drawer? Which leg do you put in your pants first? Which hand touches the button on your shirt first?

Odds are good that you could come to an answer if you thought about it. This is called a morning routine because it

is

routine. You rely on doing these things on autopilot. This whole routine has been “chunked” in your brain, which is why you have to work to recall the individual steps. It’s basically a recipe that is burned into your neurons, and you don’t “think” about it anymore.

Whatever “thinking” means.

We’re usually running on these automatic chunked patterns. In fact, most of what we see is also a chunked pattern. We rarely look at the real world; we instead recognize something we have chunked, and leave it at that. The world could easily be composed of cardboard stand-ins for real objects as far as our brains are concerned. One might argue that the essence of much of art is forcing us to see things as they are rather than as we assume them to be—poems about trees that force us to look at the majesty of bark and the subtlety of leaf, the strength of trunk and the amazing abstractness of the negative space between boughs—those are getting us to ignore the image in our head of “wood, big greenish, whatever” that we take for granted.

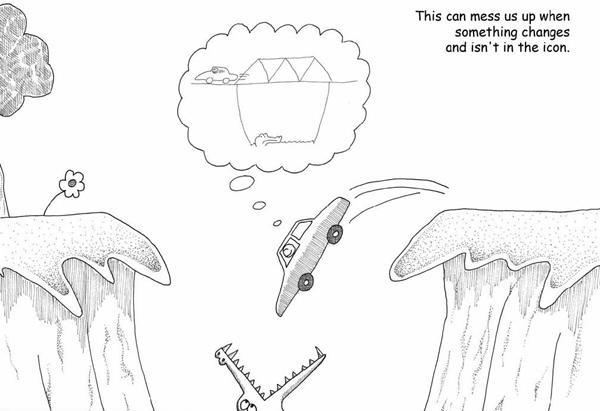

When something in a chunk does not behave as we expect it to, we have problems. It can even get us killed. If cars careen sideways on the road instead of moving forward as we expect them to, we no longer have a rapid response routine. And sadly, conscious thought is really inefficient. If you have to think about what you’re doing, you’re more liable to screw up. Your reaction times are orders of magnitude slower and odds are good you’ll get in a wreck.

How we live in a world of chunking is fascinating. Maybe you’re reading this and feeling uncomfortable about whether you’re really reading this. But what I really want to talk about is how chunks and routines are built in the first place.