Theory of Fun for Game Design (15 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

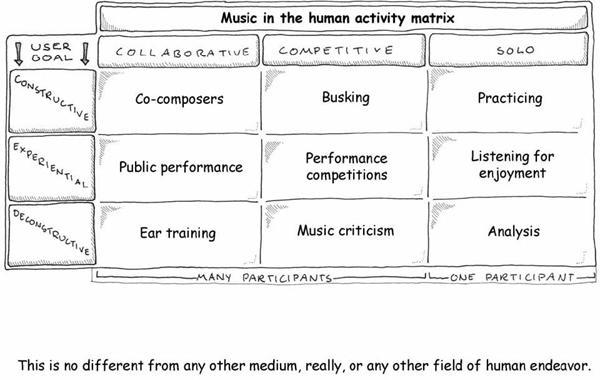

In other words, modding is just playing the game in another way, sort of like a budding writer might rework plots of characters from other writers into derivative journeyman fiction or into fan fiction. The fact that some forms of it are constructive (modding a game), experiential (playing a game), or deconstructive (hacking a game) are immaterial; the same activities are possible with a given play, book, or song. Arguably, the act of literary analysis is much the same as the act of hacking a game—the act of disassembling the components of a given piece of work in a medium to see how it works, or even to get it to do things, carry messages, or otherwise represent itself as something other than what the author of the piece intended.

Some of the activities on the first chart aren’t what you would normally term “fun,” even though they are almost all activities in which you learn patterns. We can sit here and debate whether performing music, writing a story, or drawing a picture is fun. From having training in all three, I can tell you that they are all hard work, which isn’t something we necessarily consider fun. But I derive great fulfillment from these activities. This is perhaps analogous to watching

Hamlet

on stage, reading

Lord Jim

, or viewing

Guernica

—not exactly giggly-happy-fun, but fulfilling in a different way.

The chills that go down your back are not always indicative of something that you find enjoyable. A tragedy or moment of great sorrow can cause them. The moment you recognize a pattern your body will give you the chill as a sign. Just as writing isn’t necessarily fun but might be something valuable for the writer to do, or practicing piano for hours on end might not be fun but something that gives fulfillment, engaging in interaction with games need not be fun either but might indeed be fulfilling, thought-provoking, challenging, and also difficult, painful, and even compulsive.

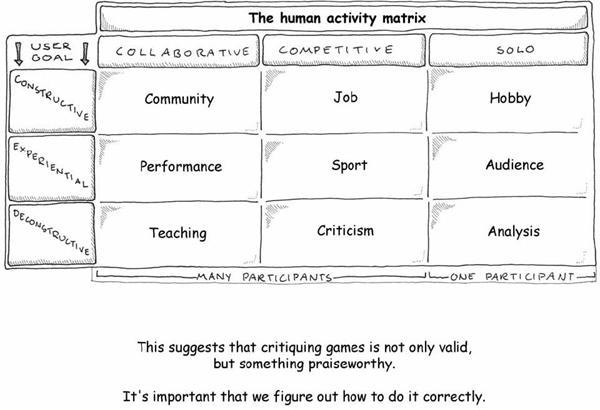

In other words, games can take forms we don’t recognize. They might not be limited to being “a game” or even a “software toy.” The definition of “game” implies certain things, as do the words “toy,” “sport,” and “hobby.” The classic definition of “game” covers only some of the boxes in the grid. Arguably, all of the boxes in the grid are fun to

someone

. We need to start thinking of games a little more broadly. Otherwise, we will be missing out on large chunks of their potential as a medium.

The reason why the rise of critique and academia surrounding games is important is because it finally adds the missing element to put games in context with the rest of human endeavor. It means their arrival as a medium. Considering how long they have been around, they’re a little late to the party.

Once games are seen as a medium, we can start worrying about whether they are a medium that permits art. All other media do, after all.

Pinning art down is tricky. We can start from the basics, though. What is art for? Communicating. That’s intrinsic to the definition. And (if you’ve bought into the premises of this book) we have seen that the basic intent of games is rather communicative as well—it is the creation of a symbolic logic set that conveys meaning.

Some apologists for games like to tout the fact that games are interactive as a sign that they are special. Others like to say that interactivity is precisely why games cannot be art, because art relies on authorial intent and control. Both positions are balderdash. Every medium is interactive—just go look on the grid.

So what is art? My take on it is simple. Media provide information. Entertainment provides comforting, simplistic information. And art provides challenging information, stuff that you have to think about in order to absorb. That’s it. Art uses a particular medium to communicate within the constraints of that medium, and often what is communicated is thoughts

about

the medium itself (in other words, a formalist approach to arts—much modern art falls in this category).

The medium shapes the nature of the message, of course, but the message can be representational, impressionistic, narrative, emotional, intellectual, or whatever else. Some art forms are solo, and some are collaborative (and they can all be made collaborative to an extent, I believe). And some media are actually the result of the collaboration of specialists in many different media, working together to present a work that is incomplete without the use of multiple media within it. Film is one such medium. And games are another.

One of the commonest points I hear about why video games are not an art form is that they are just for fun. They are just entertainment. Hopefully I’ve made it clear why that is a dangerous underestimation of fun. But most music is also just entertainment, and most novels are read just for fun, and most movies are mere escapism, and yes, even most pretty pictures are just pretty pictures. The fact that most games are merely entertainment does not mean that this is all they are doomed to be.

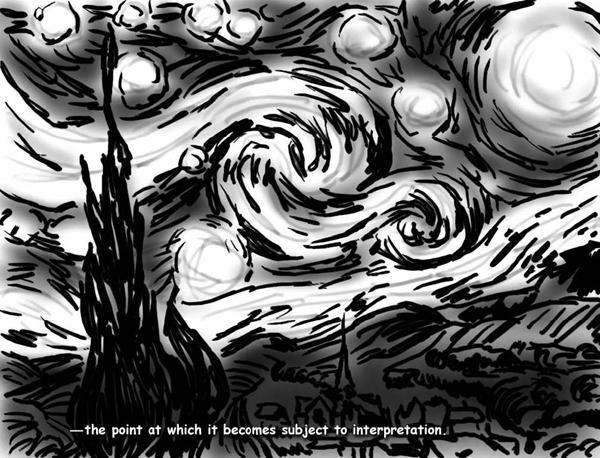

Mere entertainment becomes art when the communicative element in the work is either novel or exceptionally well done. It really is that simple. The work has the power to alter how people perceive the world around them. And it’s hard to imagine a medium more powerful in that regard than video games, where you are presented with interactivity and a virtual world that reacts to your choices.

“Well done” and “novel” mean, basically, craft. You can have well-crafted entertainment that fails to reach the level of art. The upper reaches of art are usually subtler achievements. They are pieces of work that you can return to again and again and keep learning something new. The analogy for a game would be one you can replay over and over again and keep discovering new things.

Since games are closed formal systems, that might mean that games can never be art in that sense. But I don’t think so. I think that means that we just need to decide what we want to say with a given game—something big, something complex, something open to interpretation, something where there is no single right answer—and then make sure that when the player interacts with it, they can come to it again and reveal whole new aspects to the challenge presented.

What would a game like this be?

It would be thought-provoking.

It would be revelatory.

It might contribute to the betterment of society.

It would force us to reexamine assumptions.

It would give us different experiences each time we tried it.

It would allow each of us to approach it in our own ways.

It would forgive misinterpretation—in fact, it might even encourage it.

It would not dictate.

It would immerse, and impose a worldview.

Some might say that abstract formal systems cannot achieve this. But I have seen wind course across the sky, bearing leaves; I have seen paintings by Mondrian made of nothing but colored squares; I have heard Bach played on a harpsichord; I have traced the rhythms of a sonnet; I have trod in the steps of a dance. All media are abstract, formal systems. Let’s not sell abstraction and formality short.

In fact, the toughest puzzles are the ones that force the most self-examination. They are the ones that challenge us most deeply on many levels—mental stamina, mental agility, creativity, perseverance, physical endurance, and emotional self-abnegation. They come precisely from the interactive portions of the chart, when you look at other media.

Consider the act of creation.

It’s one of the toughest things to do and do well, in human endeavor. And yet it is also one of our most instinctive actions; from a young age, we not only trace patterns but attempt to create new ones. We scribble with crayons, we ba-ba-ba our way through songs.

The fact that playing games—good ones, anyway—is fundamentally a creative act is something that speaks very well for the medium. Games, at their best, are not prescriptive. They demand that the user create a response given the tools at hand. It is a lot easier to fail to respond to a painting than to fail to respond to a game.

No other artistic medium defines itself around an intended

effect

on the user, such as “fun.” They all embrace a wider array of emotional impact. Now, we may be running into definitional questions for the word “fun” here, obviously, but even so, I’d prefer to approach things from a more formalist perspective to actually arrive at what the basic building blocks of the medium are. From a formalist point of view, music can be considered ordered sound and silence, and poetry can be considered the placement of words and gaps between words, and so on.

The closer we get to understanding the basic building blocks of games, the things that players and creators alike manipulate in interacting with the medium, the more likely we are to achieve the heights of art.