The Wooden Mile (7 page)

Authors: Chris Mould

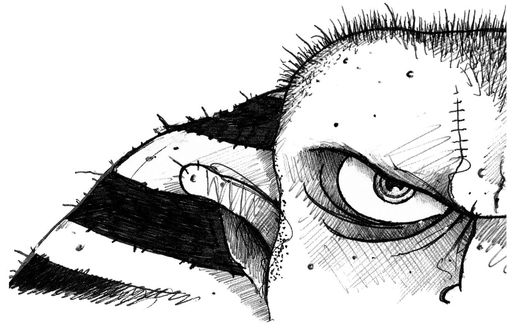

“It's a good question, Stanley,” replied Flynn, almost as if he knew it was coming. “But I got a good answer. Those folk is fishing people. They uses nets and rods to catch what they're after. They're simple people with simple ways. That gun up at your place is probably the only one on the island. I bet most of 'em ain't never even seen one. All those watchmen do is keep a lookout and make sure everybody's inside. They needs your 'elp, Stanley. You gotta get up pretty close to shoot somethin' right between the eyes.”

Stanley knew that despite their good humor they were serious. And now he had the following choice. Risk being killed by a

vicious and bloodthirsty wolf, or be lynched by angry vengeful pirates.

vicious and bloodthirsty wolf, or be lynched by angry vengeful pirates.

This really was turning into a terrible business.

Through the Telescope

A few days later, Stanley was sitting at the dinner table playing with his pie and mash. He could feel Mrs. Carelli's eyes fixed on him, and knew what was coming.

“What is it Stanley, what's the matter?”

“Nothing,” he answered so unconvincingly that she pressed him further.

“Yes there is, young Buggles. You normally

eats like a horse but I ain't seen you eat more than a crumb for days

and

you've gone quiet.

Especially

quiet.”

eats like a horse but I ain't seen you eat more than a crumb for days

and

you've gone quiet.

Especially

quiet.”

She did have a way of weeding things out of him, but Stanley would have to keep hold of this one for now.

“OK, OK,” he started. “You're right ⦠You see, the truth is, well, I'm just missing home a bit. I mean, I love it here you know but, well, I've never been away from home before. I know it's stupid.” And he started to dig into his meal. He made sure he cleaned the plate.

Mrs. Carelli's face dropped. “Stanley, I'm here for you night and day should you need me. Not just for cooking and cleaning. I know how it feels to miss someone. Years ago I lost my husband. Victor, his name was. Went on a fishing trip out at sea, he did, and never came

back. A bad storm took his boat. We found bits of it washed up on the beach.”

back. A bad storm took his boat. We found bits of it washed up on the beach.”

Stanley had stirred some feeling deep inside her and discovered something he had not known. His guilt turned into a lump that stuck awkwardly in his throat.

“I'm sorry,” he said. He could think of nothing else to say.

Â

Just as the light was fading, Stanley stepped out into the rear garden. He had left some gardening tools on the lawn and was about to bring them inside. Mrs. Carelli had asked him to do it that morning, but as usual he had gone off on some adventure around the house and forgotten to do so.

With his hands full, he turned to head back indoors when he felt a three-fingered grip fasten around his throat. It was Bill Timbers. Stanley dropped the tools at his feet.

“You all right out there, Stanley?” came Mrs. Carelli's voice from the kitchen. Timbers glared at him with a stare that told him not to make a fuss.

“I'm ⦠fine,” Stanley gasped.

“You ever seen one of these?” Timbers asked, pulling a huge knife from a binding around the bottom of his right leg. It was broad, with a bone handle and a blade that could shave the whiskers from a fly.

Stanley couldn't manage an answer. The grip around his airway had tightened and Timbers held the tip of the cutter against the point of his nose.

“'Tis a fishing knife, lad. Y'know the kind. Just right for removing the gizzards. 'Tain't no use against wolves and other such midnight nonsense, but all the same I still uses it when I'm going about me daily business, if yer get me meanin'.”

And he went on to explain to Stanley that just because he couldn't fire a gun it didn't mean he wasn't capable of doing some

irreparable damage

to whoever fell foul of him.

irreparable damage

to whoever fell foul of him.

“Tick tock, tick tock, Stanley,” he sneered, turning the blade. “Time is running out. You better make full use o' your time on Crampton

Rock now, or you'll miss yer chance and I 'as a way to deal with timewasters.”

Rock now, or you'll miss yer chance and I 'as a way to deal with timewasters.”

“Stanley, have you brought those tools in yet?” called Mrs. Carelli.

In a blink, Timbers was gone, scuttling over the wall like a long-legged lizard. Stanley picked up the equipment that lay scattered around his feet and turned inside.

Â

The next morning, Stanley was up and around in good time after a sleepless night. As he was dressing himself, he heard Mrs. Carelli talking to someone with a deep voice at the door.

“Come in,” she said, “I think he's awake.”

Stanley's heart quickened. He peered over the balcony but he could only see Mrs. Carelli.

“I won't keep him all day,” he heard the voice say.

Stanley breathed a sigh of relief. It was Lionel Grouse from the lighthouse, come to take him fishing. Mr. Grouse was all beard and smiles, with wild orange hair and a weathered face.

“Come on, young Stanley,” he grinned as the boy wandered down the staircase. “I'll make a fisherman of you yet.”

Â

Stanley had not expected to feel sick on the boat, but it was the first thing that he noticed as they breezed across choppy seawater. They dropped lobster traps as they ventured out and when they had gone some distance, Mr. Grouse prepared the fishing rods and they cast off into the sea.

Stanley was beginning to enjoy himself again. For a while all of the business of wolves and pirates disappeared. This was real life. Being out on the open water, taking in the sea air, and getting away from it all.

Up ahead a tall rock speared majestically out of the water. A few trees grew in the small space at the bottom and water crashed relentlessly around the edge.

“What's that?” asked Stanley.

“The North-East Needle, we call it,” answered Lionel. “Nothing much there except a small cave and a flock of gulls now and then. But that rock is twice the height of Candlestick Hall.”

Stanley peered upward at the tallest point, looming over them like a stooping giraffe. It looked as if it could crash down at any moment.

Suddenly he jumped: something was pulling furiously on his line! Mr.Grouse stood at his side, guiding him at the reel. But no, it was gone. It had wriggled free and he soon discovered that whatever it was had taken the hook, line and sinker with it.

“There's some big fish in these waters, Stanley, bigger than you can imagine,” said Mr. Grouse. He turned to Stanley and put the rod in its rest. “Stanley, we need to talk. I didn't bring you out here for no fancy fishing trip. Sit yourself down.”

Stanley's expression changed into a serious wide-eyed stare as he perched on a low seat.

“I want to talk to you about your Great-uncle

Bart. He was a good old friend o' mine. Oh, he'd seen some rough-ân'-tumble times at sea, but in his later life he was a peaceful, gentle man. Bart liked to fish at midnight, Stanley. He were getting out of his boat one night and didn't quite make the journey home.

Bart. He was a good old friend o' mine. Oh, he'd seen some rough-ân'-tumble times at sea, but in his later life he was a peaceful, gentle man. Bart liked to fish at midnight, Stanley. He were getting out of his boat one night and didn't quite make the journey home.

“Rumor has it that our resident werewolf was to blame. Except some folks don't like talk of werewolves. Don't like to admit we have a problem, so they cover it up, you see, just like all bad doings get covered up one way or another. I guessed you'd pick up on it before long, one way or another, so I wanted to put you straight. Mrs. Carelli ain't too keen on telling you such things, though.”

“I knew it,” gasped Stanley. “I knew the werewolf was to blame.”

Stanley was daring himself to question Mr. Grouse about William Cake, only he was

struggling to find the right way to say it.

struggling to find the right way to say it.

“That lighthouse you live in, Mr. Grouse. I bet you can see a lot from there?”

“Oh I can, lad, yeah I can.”

“Can you see the streets and houses if you look back in at the Rock? Can you see The Sweet Tooth?”

“Better than I'd like to, Stanley. Sometimes I can see more than I want to.”

Just then the sky turned black and a crack of thunder could be heard far off in the distance.

“Time we wrapped up and called it a day, I think. There's a storm blowing in.”

“I know,” said Stanley. “I can feel it.”

Â

When they reached dry land, they shared out their catch and Mr. Grouse escorted Stanley to the door with a full basket of fish.

“Don't forget, no mentioning you-know-what to you-know-who,” he instructed. “She don't like talk of wolves.”

Stanley reassured him and said goodbye, thanking him for the fishing trip. He closed the door on the day as the rain came and darkened the cobbles on the street.

He had decided that, pirates or no pirates, if Crampton Rock had a werewolf that had killed his great-uncle and he could do something about it, he would. But he had to be sure. He couldn't just assume someone was a werewolf; that was ridiculous. So he put together a plan that would reveal the truth.

Â

Two days later, Stanley had cunningly managed to get an invite to stay overnight with Mr. and Mrs. Grouse at the Lighthouseâso that he could join Mr. Grouse in looking out

for the fishing boats. This is what his mother would have called

a weak excuse

. The real reason, of course, was that Stanley wanted a good view of William Cake at midnight when the moon was full.

for the fishing boats. This is what his mother would have called

a weak excuse

. The real reason, of course, was that Stanley wanted a good view of William Cake at midnight when the moon was full.

Somehow, Stanley felt that Mr. Grouse knew what he was up to. Mrs. Grouse had put him in the room right at the top where the views were open and clear. A telescope was mounted on a stand at the top of the staircase.

Â

Darkness poured over Crampton Rock. Stanley had never had such a fantastic view of the island. From here he could see the endless stretch of the ocean, but he could also look back in at the twinkling lights of the village and the boats in the harbor. In customary fashion, the streets emptied with the fading light and the blue bulb of the moon

ran along the rooftops and rippled among the houses.

ran along the rooftops and rippled among the houses.

It was crisp and clear, but a misty sea fog flowed around under the streetlights as the town clock struck twelve. Stanley was sitting at the edge of his rickety old bed, his head resting on the stone windowsill. He had taken the telescope and held it in both hands.

Other books

Conviction: Book 3 of the Detective Ryan Series by Andrew Hess

Chasing Secrets by Gennifer Choldenko

Jaid's Two Sexy Santas by Berengaria Brown

Any Means Necessary: A Luke Stone Thriller (Book 1) by Jack Mars

A Kid for Two Farthings by Wolf Mankowitz

Silent Symmetry (The Embodied trilogy) by Dutton, JB

Shadow Magic by Jaida Jones

Dark Blue: Color Me Lonely with Bonus Content by Carlson, Melody