The Willows and Beyond (2 page)

Read The Willows and Beyond Online

Authors: William Horwood,Patrick Benson,Kenneth Grahame

Tags: #Animals, #Childrens, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Fantasy, #Classics

For the time being all thought of food and drink had fled the Rat’s mind, but a little later the Mole quietly slipped into the Rat’s house and made up a large pot of tea for the whole company He brought it out, and while it brewed he opened up his basket and finally laid out some food for the Rat on a large plate.

The Water Rat took up the mug of tea the Mole had poured for him and sipped it slowly hunching forward as he looked at the River, his hands tight about the mug as if for warmth and comfort.

“I cannot say that I fully understand what she has been trying to say to me since yesterday” he confided at last, “for the River does not use language as we do, but speaks to us in a deeper way Very often it is I who do not understand her, but I think that on this occasion she is not able to speak at all clearly of what concerns her. It is as if she is calling for help, but … that she knows we cannot give it. There! That’s what it is: she needs help, but not from us because there is nothing we can do for her.”

Ratty sounded suddenly relieved that his work of communion had found expression after so many arduous hours, but he sounded very tired as well.

“But what does she need our help

for?”

asked Nephew, who had not yet learned, as his uncle had, that on such occasions the Rat knew the questions well enough; it was the answers that had to come in their own time.

Yet perhaps because it

was

Nephew, of whom he had grown very fond in the years since he had first come to live with the Mole, the Rat did essay an answer.

“I do not know what it can be, but it’s certain it’s important and threatens her very life and possibly our own.”

There was a gasp from Nephew and Portly who had been slower than the Mole and the Otter to understand the sombre importance of what the Rat had been saying, and they stared again at the great River whose steady and relentless flow seemed as solid and eternal as the cycle of day and night, and of the seasons.

“But how — ?“ whispered Nephew.

“He doesn’t know, he can’t know,” said the Otter, replying for the Rat in a low voice, that animal having now risen.

“Mole,” the Rat called out when he had made his slow, tired way to his front door, “I’ll be well and rested in a day or two and will come and see you then. Meanwhile, let us say no more of this amongst ourselves, or to Badger. I think it better that I talk to him myself about it first, for idle chatter on matters of moment is to nobody’s advantage, least of all

hers.”

“Uncle,” began Nephew an hour later, after the little group had dispersed and the two moles were nearing Mole End by the light of the stars, “this

is

a serious business, isn’t it?”

His uncle had said hardly a word since they had crossed the Iron Bridge, and in the last quarter of an hour his pace had slowed, evidence that he was deep in thought. Now he stopped, sniffed appreciatively at the night air, and leaned upon a gate that led into one of the pasture fields.

“No doubt of it, Nephew, none whatsoever. Ratty isn’t given to making things up, and he never makes light of River business. I cannot think what the matter can be, and nor shall I try, for in that department we must leave ourselves in the good hands of Ratty and Otter, and to some extent in Portly’s as well, for he is coming along very well, very well indeed.

“Meanwhile, as Ratty said, ‘idle chatter’ will help nobody, and I shall desist from it. Now, did you succeed in stopping the rattle in the window, and easing the front door somewhat?”

“I did,” said Nephew good-humouredly, the more so because such jobs were much easier without the house-proud Mole fussing about, and he had been glad that his uncle had followed his gentle hint and made himself scarce for the day.

“There’s still a good deal of work to do on the other windows, however, and I will need your help holding the ladder on that highest window of all, which needs a good clean and rub-down, and then some fresh paint.”

“Even more than that I fancy,” said the Mole, “for I put in that window myself when I first came to Mole End, and that’s a good many years ago — before you were born.”

Talking in this comforting manner, they resumed the last stage of their journey and once back in the security of Mole End they soon turned in. It had been a long day, and a worrying one, but the Mole always said that a good night’s sleep cleared the mind and made things look different, and very often a good deal better; and often he was right.

If he had hoped for a lie-in, however, he was disappointed, for the sun seemed barely to have risen when there was a rat-tat-tat at the door.

“That must be Ratty!” he said, as he rose from his bed and searched for his dressing-gown. “He must have made a bit more sense of what the River was trying to tell him and come over at once to tell me.”

Rat-tat-tat! went the knocker once more, rousing Nephew from his slumbers too.

Grumbling a little, and calling to Ratty to be patient

if

you please, the Mole slid back the bolts and finally opened the door.

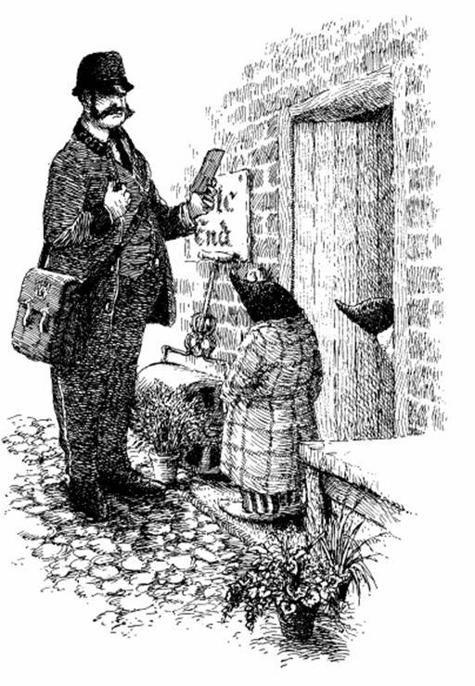

“Ratty, you’re always welcome,” began the Mole, “but do remember that not everybody is as wide awake at this hour as —But it was not the Rat. It was a solid gentleman in a blue and red uniform, and he carried a brown canvas satchel with a red crown upon it, above which were embroidered the words “Royal Mail”.

The Mole saw at once the mistake the postman had made.

“It’ll be Mr Toad of Toad Hall you want,” he said, his normal good humour returning as he saw that the weather was fine and another good day seemed certain, “but I’m very much afraid you’ve come too far.”

“I know where Mr Toad lives,” said the postman slowly “Everybody knows

him.

But I can’t say as we’ve ever had to deliver further afield than his establishment, not in my experience and that goes back a good way now.”

“Ah,” said the Mole equably, feeling that in some way he may have called into question the postman’s professionalism.

“You’re Mr Mole of Mole End, I take it, seeing as you’re mole-like and your house is named ‘Mole End’?”

“That is correct,” concurred the Mole.

“So you’re not Mr Water Rat? And nor is

he,

I take it, since he, too, is mole-like?”

Nephew had appeared at the door behind the Mole and the postman was staring at him rather suspiciously.

“Neither of us is the Water Rat,” said the Mole, feeling that simple agreement was the best approach with this gentleman.

“It’s easier in the Town,” said the postman wearily. “There’s numbers on the houses there. If I had my way I would have the law changed and get numbers put on every house in the land.”

“I see,” said the Mole, “but do you not feel that it would be pleasant to retain the house name as well?”

“Can’t see the point,” said the postman.

“No, I don’t suppose you can,” said the Mole.

“I can’t stop here all day talking to you, now can I?” said the postman suddenly “The letters of the land must be delivered — not to mention

other things.”

Mole glanced at his satchel, wondering if it might contain some of those “other things”, and if so if they might be dangerous in some way But the bag appeared to be empty, which was perhaps not surprising since Mole End was the last house in this direction for a great many miles.

“Would you like a cup of tea and some buttered toast?” offered the Mole, thinking that perhaps that was the way to deal with postmen.

“That is against all the regulations,” said the postman with considerable severity, “and it is as well that you did not include with that invitation the suggestion — a hint would have been enough — that alcoholic beverage was included, or else I would have had to make a citizen’s arrest and turn you and every other person resident in this house over to the magistrates.”

“Well I —“ began the perplexed Mole, who had never thought that the offer of sustenance to a visitor might land him in court.

“Don’t you think, sir, that it would be better if you said nothing more on the subject of tea and toast? Instead, perhaps you could just try to give me a straight and unequivocal answer to a simple question: if Mr Rat does not live here, where does he live?”

“On the other side of the River,” said the Mole, pointing down through the trees. “It’s about half an hour or so if you go back the way you’ve come and over the Iron Bridge, but a good deal quicker by boat.”

“Very droll,” said the postman with a scowl. “We are not issued with boats.”

“I could perhaps take the letter or package to Ratty myself, he is a good fr—”

“Sir, you have an unfortunate habit of saying the wrong thing: I would not repeat that suggestion if I were you, because purloining mail is deemed a criminal rather than a civil offence!”

The Mole was not a little affronted by the postman’s attitude, but he was also most curious and intrigued, for to his certain knowledge the Rat had no more experience with the Royal Mail, in either the receiving or sending departments, than he had. He was reluctant to ask further questions, since he did indeed seem to say or ask the wrong thing and had not quite realized the risks attached to dealing with postmen, but quite suddenly the postman softened a little and offered some information.

“In any case,” he said, “it isn’t a letter”

“Not a letter,” said the Mole, feeling that repetition of what was said to him was the safest approach.

“Nor a package.”

“Ah,” said the Mole. “Nor a package.”

“Not even an ‘Address Unknown Return To Sender’.”

“Not even that!” exclaimed the Mole, feeling that he was beginning to get the hang of things.

“No, sir, we don’t often get to deliver one of these, and seeing as it’s caused me so much trouble I’m not sure I want to deliver another one.”

He dug deep into the bag.

“What is it?” asked the Mole, quite forgetting himself.

But now the postman seemed willing enough to talk. “This,” he said, “is a Customer Instruction to Collect — that’s on this side — and Customer Permission to Receive and Take Away — that’s on

this

side. Collect from the Town Head Post Office, that is, seeing as the item is too big, or bulky or in some other way not party to the normal regulations. Clearly we cannot as postmen undertake the risk to our persons of delivering such items, so the customer must take it upon himself.”

The Mole saw at once that he had been quite correct to think that “other things” might be in some way dangerous. He permitted himself a momentary and uncharacteristic sense of selfish relief that it was not he who was to receive this Instruction to Collect, but the Rat. But then the Rat was more practical than he and would no doubt know what to do, or soon work it out.

“What is the nature of the item?” asked Nephew, as curious as his uncle.

“I am not permitted to tell you that,” said the postman, “but there is nothing to prevent me reading out what is upon the card, and nothing to prevent you hearing me do so.”

He held up the card, squinted at it long and hard, and uttered a single and most startling word.

“Livestock,” he said.

“I beg your pardon?” said the Mole.

“I shall endeavour to read out this word again, sir, and I trust you will endeavour to hear it this time.”

He held up the card once more, peered at it, and uttered that astonishing word again, quite clearly, and for all to hear.

“Livestock,” said he.

“And Mr Rat is to collect it?”

“Or them, sir; you never can tell with livestock.”

“Are you permitted to read anything else on the card which may give us a clue about this matter?” continued the Mole, his curiosity undeniable.

“The only other item that may have relevance, sir —and beyond this I know nothing myself, for incoming mail and other items is a different department, of course — concerns the

source

of said item. That often gives a clue. For example, if the source were ‘The Cheesery, Wensleydale, Yorkshire’, you might reasonably conclude it was a Wensleydale cheese.”

“But that wouldn’t be livestock,” said the Mole.

“I would not be quite so sure upon that point, sir, if I were you, given some of the cheeses I have seen lingering in the Sorting Office.”