The Willows and Beyond (10 page)

Read The Willows and Beyond Online

Authors: William Horwood,Patrick Benson,Kenneth Grahame

Tags: #Animals, #Childrens, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Fantasy, #Classics

“Hmmm, what’s this then?” Toad said to himself. “I don’t seem to have seen it before.”

Even as he read the title and the author’s name, he felt a thrill of vocation and purpose, and knew at once this was the light in the hiking darkness he had been seeking.

“Yes, O yes!” he whispered as he turned the pages, reading every word and each terse chapter with mounting speed and excitement, for here at last was a book that told him in terms he could understand how to deal —

exactly

how to deal — with those who refused to follow a leader’s command in matters of educational exercise: in short, those like Master Toad.

The book was entitled

Hiking For Leaders With Novices: Do’s, Don’t’s and Definitely Not’s,

by Colonel J. R. Wheeler Senior, Member of the Alpine Club and Hiking Adviser to the Royal Marines School of Music (Yachting Section).

It was that felicitous phrase “Leaders With Novices that so appealed to Toad, for a leader he felt himself to be, and with a novice he would be venturing forth. Wheeler, an ex-Indian Army officer and conqueror of the Nangha-Dhal in the Himalaya, had a good deal to say on all aspects of hiking, and was especially strong on boots, maps, thorn-proof breeches and hunting knives. He had a good section on protective headgear (against falling rocks) and goggles (against sand and snow), which he felt should be worn at all times, and an invaluable few pages on certain technicalities often overlooked in lesser tomes upon the subject, namely rope work, compass work and night-craft. But it was in his excellent writing on the art of effective leadership, about which Toad already felt himself to know a good deal, that Wheeler won his latest reader’s heart and mind.

Wheeler’s notion of leadership was clear and to the point:

The leader is

leader

, and must at all times be on his guard against insubordination and the dangers of paying too much attention to the weak and feeble in his group. These must be weeded out and made an example of.

Where native porters are concerned, the leader is advised always to hire two or three extra (on my Nangha-Dhal Expedition I took on an extra porter for every four days of the journey, but conditions were extreme) so that they might be disposed of en route to encourage the others not to slacken.

The good leader will always remain in front and not allow another to take his place there, otherwise, like the African pack lion, he is done for.

Wheeler’s advice on a range of matters was of a kind that appealed especially to one such as Toad:

It will frequently happen, and a leader should certainly not be disheartened by this, that the way will be lost. I make it a practice, and I urge novice leaders to learn from my mistakes and follow this advice rigorously, on no account to tell others in my party where I intend going. This ensures that wherever one may arrive, one appears to have intended that as one’s destination.

But it was another piece of advice in the book that finally gave Toad the will to try out the equipment he had avoided actually using for so many weeks.

The true leader should not feel obliged to know or understand the use of every piece of equipment or the practice of every technique, for he will have employed those in his expedition who should be able and willing advisers on such matters. However, the effective leader will need to appreciate the importance of

seeming

to know what he is talking about and

looking

as if he knows what he is doing. This inspires confidence in those he leads, and keeps them at their tasks.

Therefore, a leader is strongly advised to try on the equipment till he is used to wearing it, and to find some quiet place where, unobserved, he can get the feel’ of it with a short solo hike or two. In this way he will ensure that he looks the part.

Thus instructed, Toad had risen from his reading couch and that very evening, having ensured Master Toad was at his academic labours, repaired to the gun room to begin his further familiarization with hiking equipment.

With Colonel Wheeler’s help he was pleased to discover the purpose of the prismatic compass, but since it was difficult to hold and read, clearly faulty (the needle seemed to wobble about a good deal and refused to stay in the same place)

and

heavy, he discarded it.

Wheeler’s book made rather more sense for Toad of an item for which he had been unable to see a use, but which once explained he saw as an essential. This was an alpenstock, a thick, rude stave almost as tall as himself, with a heavy iron spike at one end, deadly sharp.

Apart from being an emblem of leadership, the alpenstock is useful for a great many purposes, such as killing game, the light disciplining of porters, bridging crevasses, forming stretchers and, in extremis, quelling native rebellions.

Toad trusted that its primary usage, as symbol and prop to his leadership, was the only one on this impressive list he would need it for, and took up the huge stick with relish, holding it aloft like a crusader’s sword and inadvertently striking the ceiling above.

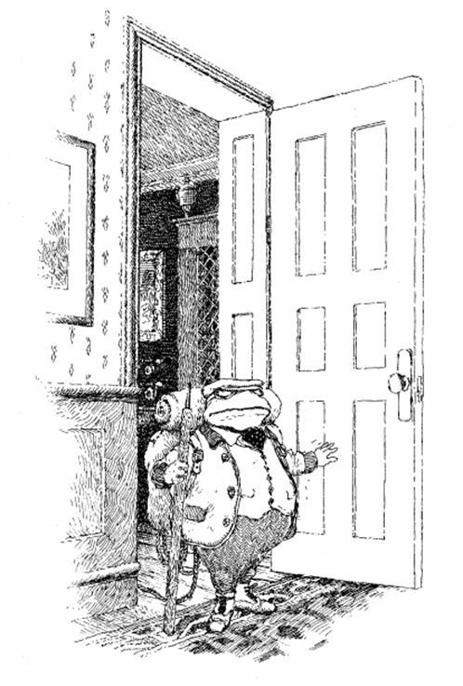

Now feeling, as so often in his life, that nothing ventured was nothing gained, Toad quickly donned the thorn-proof suit and cap, hoisted the large haversack up onto his shoulders, placed the goggles over his eyes against sandstorms and, holding his trusty alpenstock, opened the gun-room door to check that there was nobody about.

Seeing the coast was clear, he made his way through the conservatory and out into the dusk, and headed down towards the River Bank. When he reached the Iron Bridge, he struggled up its steep face in a slow and measured way (it reminded him of his imaginary ascent some evenings before of Mont Blanc) and found himself trotting down the other side in an alarmingly accelerating manner (the weight of the haversack, albeit stuffed only with wrapping paper, was not quite what he was used to) and straight into the hedge beside the road.

There he rested awhile till, imagining he heard voices and feeling suddenly nervous to be out in the dark alone, he gripped his trusty alpenstock, leant on it as he pulled himself up and turned back towards his home. The goggles did not greatly improve his vision, and fancying he saw the outline of people upon the bridge he raised them up to rest upon his forehead. Then, seeing that he was mistaken, he continued his journey home unobserved, stowed away the gear and joined the unsuspecting Master Toad for supper.

It was after dinner that night — over a glass of mulled wine — that Mole and Nephew brought the news of the sighting that sent Toad into such a panic. To think that even as he had been climbing the Iron Bridge, a malevolent creature was skulking somewhere nearby! He rapidly dropped his plans to put his hiking equipment through another test the following night, and decided to restrict his research to the safety of his own bedroom.

As the days went by with no further sightings, however, his initial panic gradually lessened. He began to agree with Mole’s view that the “Beast” was merely some vagrant, who was not likely to be seen again.

Having thus reassured himself and dipped once more into Colonel Wheeler’s excellent book, he decided to take advantage of his ward’s absence to try again.

This time he put a few light items in his haversack to test his mettle, and once more headed off for the Iron Bridge in his alpine outfit, feeling it would be wise to ascend and descend a few times as training for his back and calf muscles.

He saw no sign of the Beast, but after a while he heard boat-like sounds from the River and guessed that Otter, Master Toad and the others were coming back after their day of River work. So confident by now did he feel of his attire, and so monarch-like did he feel with the alpenstock in his hand, that at first he thought he might go and greet them and reveal his new pursuit.

But he thought again, for the gloaming would not show his gear in its fullest splendour, and he felt suddenly very tired. As he strove to climb the humped bridge once more, his breath came out in grunts and groans, and the haversack seemed to weigh him down even more. So he turned about, went home and enjoyed an invigorating supper before venturing out to find Master Toad, and make clear his resolve to brook no further excuses and to take him hiking the very next day.

As they returned home together, Toad was pleased and gratified that Master Toad seemed so obedient, and stuck so close by his side. Indeed he seemed very eager to get home to bed and so be ready for the morrow.

“Monsieur,” he declared, using that form of address he reserved for formal occasions when a certain respect for his elders was called for, “I ‘ave an admission to make. Tonight we ‘ave seen the Beast — an hour or two before you came.

“The Beast of the Iron Bridge?” gasped Toad. “On that bridge ‘e stood, threatening us! Yet as we walked back later you, my guardian, showed no fear!”

Toad suddenly felt rather faint. “I — I did not know —“he spluttered.

“You were brave and bold and gave me much confidence. Tomorrow, Pater, I will follow your lead in ‘iking wherever you wish, and I shall not complain!”

With these grand and respectful words Master Toad retired to bed, leaving Toad astonished and bewildered as he stared out of the conservatory window to see if he might espy the Beast, but saw only his own reflection.

V

Mole’s Birthday

Surprise

Mole and Ratty were sitting on Ratty’s porch with mugs of tea in their hands and shawls over their knees. Having enjoyed a lingering lunch by the fireside, they were now making the most of the Indian summer by watching the River drift by in this companionable way.

“Do you know, Mole,” observed the Rat, “I cannot now remember a time when we did not know each other, and were constantly able to look forward — and back! — to picnic and tea, courtesy yourself, and blissful days afloat, courtesy my boat.”

“And your skill,” said the Mole.

“That’s as maybe,” said the Rat, “but the fact is that one way and another we have a good deal to be thankful for, have we not?”

It was not often that the Rat mused thus, and the Mole was rather surprised at it, but then he knew very well that the Rat had not been quite himself lately. He had seemed more often tired than in yesteryear, and a little more inclined to stay in his seat enjoying an extra cup of tea or two than to embark on some urgent River errand.

The Mole did not in the least object to lingering in the Rat’s company in this way for there was no friendship that gave him more constant and lasting pleasure. These days the opportunities to do so at the Rat’s house were rarer, for Young Rat was in residence, and daily giving the Rat much assistance and quiet company But that day he had gone off with the Otter and Portly and Mole told himself, wrongly as it happened, that was why the Rat had invited him over.