The Way Through The Woods (6 page)

Morse had finished – and there was a long silence between them during which he drained his whisky, she her brandy,

'Another?' asked Morse.

'Yes. But I'll get them. The cheque he gave me was more tha generous.' The voice was matter-of-fact, harder now, and Morse knew that the wonderful magic had faded. When she returned with the drinks, she changed her place and sat primly opposite him.

'Would you believe me if I said the suitcase I brought with me belongs to my mother, whose name is Cassandra Osborne?'

'No,' said Morse. For a few seconds he thought he saw a sign of a gentle amusement in her eyes, but it was soon gone.

'What about this – this "married man who lives in Oxford"?'

'Oh, I know all about him.'

You

what?'

Involuntarily her voice had risen to a falsetto squeak, and two or three heads had turned in her direction.

what?'

Involuntarily her voice had risen to a falsetto squeak, and two or three heads had turned in her direction.

'I rang up the Thames Valley Police. If you put any car number through the computer there -‘

‘- you get the name and address of the owner in about ten seconds.'

'About

two

seconds,' amended Morse. 'And you did

that?'

'I did that.'

two

seconds,' amended Morse. 'And you did

that?'

'I did that.'

'God! You're a regular shit, aren't you?' Her eyes blazed with anger now.

'S'funny, though,' said Morse, ignoring the hurt. 'I know

his na

me – but I still don't know

yours

.' ‘Louisa, I told you.'

his na

me – but I still don't know

yours

.' ‘Louisa, I told you.'

‘No. I think not. Once you'd got to play the part of Mrs Something Hardinge, you liked the idea of "Louisa". Why not? You may not know all that much about Coleridge. But about Hardy? That's different. You remembered that when Hardy was a youth he fell in love with a girl who was a bit above him in class and wealth and privilege, and so he tried to forget her. In fact he spent all the rest of his life trying to forget her.'

She was looking down at the table as Morse went gently on: ‘Hardy never really spoke to her. But when he was an old man he used to go and stand over her unmarked grave in Stinsford churchyard.'

It was Morse's turn now to look down at the table

‘Would you like some more coffee, madame?' The waiter smiled:ely and sounded a pleasant young chap. But 'madame' shook -~ nead, stood up, and prepared to leave

‘Claire – Claire Osborne – that's my name.'

‘Well, thanks again – for the paper, Claire.'

‘That's all right.' Her voice was trembling slightly and her eyes; suddenly moist with tears.

‘Shall I see you for breakfast?' asked Morse.

‘No. I'm leaving early.'

‘Like this morning.'

'Like this morning.'

‘I see,' said Morse.

'Perhaps you see too much.'

'Perhaps I don't see enough.'

'Goodnight – Morse.'

'Goodnight. Goodnight, Claire.'

When an hour and several drinks later Morse finally decided to retire, he found it difficult to concentrate on anything else except taking one slightly swaying stair at a time. On the second floor, Room 14 faced him at the landing; and if only a line of light had shown itself at the foot of that door, he told himself that he might have knocked gently and faced the prospect of the wrath to come. But there was no light.

Claire Osborne herself lay awake into the small hours, the duvet kicked aside, her hands behind

her

head, seeking to settle her restless eyes; seeking to fix them on some putative point about six inches in front of her nose. Half her thoughts were still with the conceited, civilized, ruthless, gentle, boozy, sensitive man with whom she had spent the earlier hours of that evening; the other half were with Alan Hardinge, Dr Alan Hardinge, fellow of Lonsdale College, Oxford, whose young daughter, Sarah, had been killed by an articulated lorry as she had cycled down Cumnor Hill on her way to school the previous morning.

chapter tenher

head, seeking to settle her restless eyes; seeking to fix them on some putative point about six inches in front of her nose. Half her thoughts were still with the conceited, civilized, ruthless, gentle, boozy, sensitive man with whom she had spent the earlier hours of that evening; the other half were with Alan Hardinge, Dr Alan Hardinge, fellow of Lonsdale College, Oxford, whose young daughter, Sarah, had been killed by an articulated lorry as she had cycled down Cumnor Hill on her way to school the previous morning.

Mrs Kidgerbury was the oldest inhabitant of Kentish Town, I believe, who went out charing, but was too feeble to execute her conceptions of that art(Charles Dickens,

David Copperfield)

With a sort of expectorant 'phoo', followed by a cushioned 'phlop', Chief Superintendent Strange sat his large self down opposite Chief Inspector Harold Johnson. It was certainly not that he enjoyed walking up the stairs, for he had no pronounced adaptability for such exertions; it was just that he had promised his very slim and very solicitous wife that he would try to get in a bit of exercise at office wherever possible. The trouble lay in the fact that he usually too feeble in both body and spirit to translate such resolve into execution. But not on the morning of Tuesday, 30 June 1992, four days before Morse had booked into the Bay Hotel…

THE Chief Constable had returned from a fortnight's furlough the previous day, and his first job had been to look through the correspondence which his very competent secretary had been unable, or unauthorized, to answer. The letter containing the ‘Swedish Maiden' verses had been in the in-tray (or so she thought) about a week. It had come (she thought she remembered) in a cheap brown envelope addressed (she

did almost

remember this) to 'Chief Constable Smith (?)'; but the cover had been thrown away – sorry! – and the stanzas themselves had lingered there, wasting as it were their sweetness on the desert air – until Monday the

29

th

.

did almost

remember this) to 'Chief Constable Smith (?)'; but the cover had been thrown away – sorry! – and the stanzas themselves had lingered there, wasting as it were their sweetness on the desert air – until Monday the

29

th

.

The Chief Constable himself had felt unwilling to apportion blame: five stanzas by a minor poet named Austin were not exactly the pretext for declaring a state of national emergency, were they? yet the 'Swedish' of the first line combined with the 'maiden' of penultimate line had inevitably rung the bell, and so he had in turn rung Strange, who in turn had reminded the CC that it was DCI Johnson who had been – was – in charge of the earlier investigations.

A photocopy of the poem was waiting on his desk that day when] Johnson returned from lunch.

It had been the following morning, however, when things had really started to happen. This time, certainly, it

was

a cheap brown envelope, addressed to 'Chief Constable Smith (?), Kidlington Police, Kidlington' (nothing else on the cover), with a Woodstock! postmark, and a smudged date that could have been '27 June' that was received in the post room at HQ, and duly placed with the CC's other mail. The letter was extremely brief:

was

a cheap brown envelope, addressed to 'Chief Constable Smith (?), Kidlington Police, Kidlington' (nothing else on the cover), with a Woodstock! postmark, and a smudged date that could have been '27 June' that was received in the post room at HQ, and duly placed with the CC's other mail. The letter was extremely brief:

Why are you doing nothing about my letter?

Karin Eriksson

The note-paper clearly came from the same wad as that used for the first letter: 'Recycled Paper – OXFAM • Oxford • Britain’ printed along the bottom. There was every sign too that the note was written on the same typewriter, since the four middle characters of 'letter' betrayed the same imperfections as those observable in the Swedish Maiden verses.

This time the CC summoned Strange immediately to his office

'Prints?' suggested Strange, looking up from the envelope and note-paper which lay on the table before him.

'Waste o' bloody time! The envelope? The postman who collected it – the sorter – the postman who delivered it – the post room people here – the girl who brought it round – my secretary…’

'You,

sir?'

sir?'

'And me, yes.'

'What about the letter itself?'

'You can try if you like.'

'I'll get Johnson on to it -'

'I don't want Johnson. He's no bloody good with this sort of case. I want Morse on it.'

'He's on holiday.'

'First I've heard of it!'

'You've been on holiday, sir.'

'It'll have to be Johnson then. But for Christ's sake tell him to get off his arse and actually

do

something!'

do

something!'

For a while Strange sat thinking silently. Then he said, 'I've got a bit of an idea. Do you remember that correspondence they had in

The Times

a year or so back?'

The Times

a year or so back?'

'The Irish business – yes.'

'I was just thinking – thinking aloud, sir – that if you were to ring

The Times

-'

The Times

-'

"Me? What's wrong with

you

ringing 'em?'

you

ringing 'em?'

Strange said nothing.

'Look! I don't care what we do so long as we do

something

quick!'

something

quick!'

Strange struggled out of his seat.

‘How does Morse get on with Johnson?' asked the CC.

‘He doesn't.'

‘Where is Morse going, by the way?'

‘Lyme Regis – you know, where some of the scenes in

Persuasion

set.'

Persuasion

set.'

‘Ah.' The CC looked suitably blank as the Chief Superintendent lumbered towards the door.

‘There we are then,' said Strange. 'That's what I reckon we ought to do. What do you say? Cause a bit of a stir, wouldn't it? Cause a

bit of interest?'

bit of interest?'

Johnson nodded. 'I like it. Will you ring

The Times,

sir?'

The Times,

sir?'

‘What's wrong with

you

ringing 'em?'

you

ringing 'em?'

‘Do you happen to know-?'

‘You – can – obtain – Directory – Enquiries,' intoned Strange stically, 'by dialling one-nine-two.' Johnson kept his lips tightly together as Strange continued: 'And while I'm here you might as well

remind me about the case. All right’

So Johnson reminded him of the case, drawing together the threads of the story with considerably more skill than Strange had thought him capable of.

chapter elevenNec scit qua sit iter

(He knows not which is the way to take)

(Ovid,

Metamorphoses II)

karin eriksson had been a 'missing person' enquiry a year ago when her rucksack had been found; she was a 'missing person enquiry’ now. She was not the subject of a murder enquiry for simple reason that it was most unusual – and extremely tricy – to mount a murder enquiry without any suspicion of foul play, with no knowledge of any motive, and above all without

body.

body.

So, what

was

known about Miss Eriksson?

was

known about Miss Eriksson?

Her mother had run a small guest-house in Uppsala, but sc after the disappearance of her daughter had moved back to roots – to the outskirts of Stockholm. Karin, the middle of three daughters, had just completed a secretarial course, and had passed her final examination, if not with distinction at least with a reasonable hope of landing a decent job. She was, as all agreed, of the classic Nordic type, with long blonde hair and a bosom which liable to monopolize most men's attention when first they met her. In the summer of 1990 she had made her way to the Holy Land without much money, but also without much trouble it appeared until reaching her destination, where she may or may not have been the victim of attempted rape by an Israeli soldier. In 1991 she had determined to embark on another trip overseas; been determined too, by all accounts, to keep well clear of the military wherever she went, and had attended a three-month martial arts course in Uppsala, there showing an aptitude and perseverarnce which had not always been apparent in her secretarial studies. In any case, she was a tallish (5 foot 8½ inches), large-boned, athletic young lady, who could take fairly good care of herself, thank you very much.

The records showed that Karin had flown to Heathrow on Wednesday, 3 July 1991, with almost £200 in one of her pockets, a multi-framed assemblage of hiking-gear, and with the address of a superintendent in a YWCA hostel near King's Cross. A few days in London had apparently dissipated a large proportion of her English currency; and fairly early in the morning of Sunday, 7 July, she had taken the tube (perhaps) to Paddington, from where (perhaps) she had made her way up to the A40, M40 -towards Oxford. The statement made by the YWCA superintendent firmly suggested that from what Karin had told her she would probably be heading – in the long run – for a distant relative living

mid-Wales.

In all probability K. would have been seen on one of the feeder roads to the A40 at about 10 a.m. or so that day. She would have been a distinctive figure: longish straw-coloured hair, wearing a pair of faded-blue jeans, raggedly split at the knees à la mode. But particularly noticeable – this from several witnesses – would have been the yellow and blue Swedish flag, some 9 inches by 6 inches, stitched across the main back pocket of her rucksack; and around her neck (always) a silk, tasselled scarf in the same national colours – sunshine and sky.

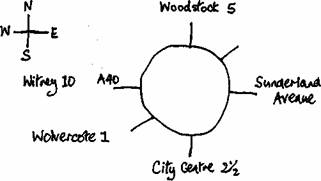

Two witnesses had come forward with fairly positive sightings of a woman, answering Karin's description, trying to hitch a lift between the Headington and the Banbury Road roundabouts in Oxford. And one further witness, a youth waiting for a bus at the top of the Banbury Road in Oxford, thought he remembered seeing her walking fairly purposefully down towards Oxford that day. The time? About noon – certainly! – since he was just off for a drink at the Eagle and Child in St Giles'. But more credence at the time was given to a final witness,.a solicitor driving to see invalid mother in Yarnton, who thought he could well have her walking along Sunderland Avenue, the hornbeam-lined road linking the Banbury Road and the Woodstock Road round-abouts.

At this point Johnson looked down at his records, took out a amateurishly drawn diagram, and handed it across to Strange.

‘That's what would have faced her, sir – if we can believe she even got as far as the Woodstock Road roundabout.'

Other books

Cloudburst Ice Magic by Siobhan Muir

The Billionaire and The Pop Star by Silver, Jordan

After Tamerlane by John Darwin

Bad Boy's Touch (Firemen in Love Book 3) by Starling,Amy

Greyrawk (Book 2) by Jim Greenfield

Eve of Warefare by Sylvia Day

His Excellency: George Washington by Joseph J. Ellis

Elsewhere by Gabrielle Zevin

The Scent of Rain and Lightning by Nancy Pickard

Haunting Embrace by Erin Quinn