The War of the Ring

Read The War of the Ring Online

Authors: J. R. R. Tolkien

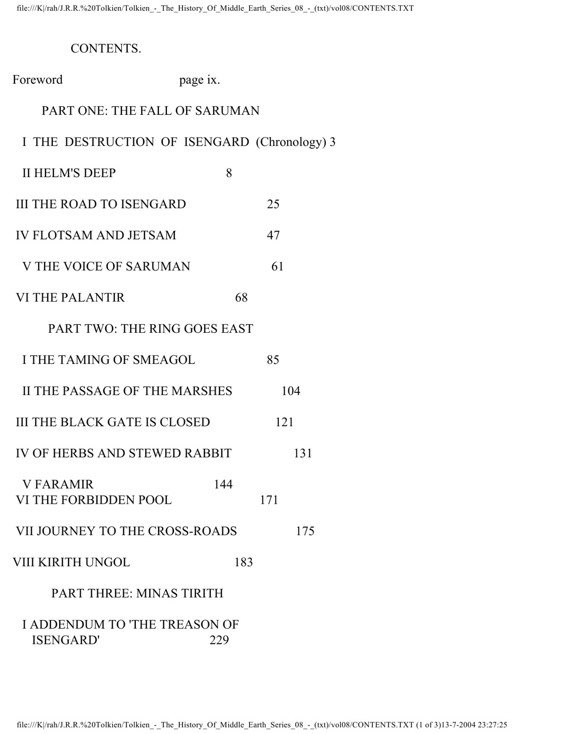

Foreword page ix.

PART ONE: THE FALL OF SARUMAN

I THE DESTRUCTION OF ISENGARD (Chronology) 3

II HELM'S DEEP 8

III THE ROAD TO ISENGARD 25

IV FLOTSAM AND JETSAM 47

V THE VOICE OF SARUMAN 61

VI THE PALANTIR 68

PART TWO: THE RING GOES EAST

I THE TAMING OF SMEAGOL 85

II THE PASSAGE OF THE MARSHES 104

III THE BLACK GATE IS CLOSED 121

IV OF HERBS AND STEWED RABBIT 131

V FARAMIR 144

VI THE FORBIDDEN POOL 171

VII JOURNEY TO THE CROSS-ROADS 175

VIII KIRITH UNGOL 183

PART THREE: MINAS TIRITH

I ADDENDUM TO 'THE TREASON OF

ISENGARD' 229

II BOOK FIVE BEGUN AND ABANDONED

(i) Minas Tirith 231

(ii) The Muster of Rohan 235

(iii) Sketches for Book Five 252

III MINAS TIRITH 274

IV MANY ROADS LEAD EASTWARD (1) 296

V MANY ROADS LEAD EASTWARD (2) 312

VI THE SIEGE OF GONDOR 323

VII THE RIDE OF THE ROHIRRIM 343

VIII THE STORY FORESEEN FROM FORANNEST 359

IX THE BATTLE OF THE PELENNOR FIELDS 365

X THE PYRE OF DENETHOR 374

XI THE HOUSES OF HEALING 384

XII THE LAST DEBATE 397

XIII THE BLACK GATE OPENS 430

XIV THE SECOND MAP 433

Index 440

ILLUSTRATIONS.

Shelob's Lair first frontispiece Dunharrow second frontispiece Orthanc '2', '3' and '4' page 33

Orthanc '5' 34

A page from the first manuscript of 'The Taming of Smeagol' 90

Two early sketches of Kirith Ungol 108

Third sketch of Kirith Ungol 114

Frodo's journey to the Morannon (map) 117

Minas Morghul and the Cross-roads (map) 181

Plan of Shelob's Lair (1) 201

Kirith Ungol 204

Plan of Shelob's Lair (2) 225

Dunharrow 239

Harrowdale (map) 258

The earliest sketch of Minas Tirith 261

The White Mountains and South Gondor (map) 269

Minas Tirith and Mindolluin (map) 280

Plan of Minas Tirith 290

Starkhorn, Dwimorberg and Irensaga 314

The Second Map (West) 434

The Second Map (East) 435

FOREWORD.

The title of this book comes from the same source as The Treason of Isengard, a set of six titles, one for each 'Book' of The Lord of the Rings, suggested by my father in a letter to Rayner Unwin of March 1953 (The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien no. 136). The War of the Ring was that proposed for Book V, and I have adopted it for this book since the history of the writing of Book V constitutes nearly half of it, while the first part concerns the victory of Helm's Deep and the destruction of Isengard. The second part describes the writing of Frodo's journey to Kirith Ungol, and this I have called 'The Ring Goes East', which was the title proposed by my father for Book IV.

In the Foreword to The Return of the Shadow I explained that a substantial collection of manuscripts was left behind in England when the bulk of the papers went to Marquette University in 1958, these manuscripts consisting for the most part of outlines and the earliest narrative drafts; and I suggested that this was a consequence of the papers being dispersed, some in one place and some in another, at that time. But the manuscript materials for The Return of the King were evidently preserved with the main body of the papers, for nothing of Books V and VI was left behind beyond some narrative outlines and the first draft of the chapter 'Minas Tirith'. For my account of Book V therefore I have been almost wholly dependent on the provision from Marquette of great quantities of manuscript in reproduction, without which the latter part of The War of the Ring could not have been written at all. For this most generous assistance I express my gratitude to all concerned in it, and most especially to Mr Taum Santoski, who has been primarily responsible for the work involved. In addition he has advised me on many particular points which can be best decided by close examination of the original papers, and he has spent much time in trying to decipher those manuscripts in which my father wrote a text in ink on top of another in pencil. I thank also Miss Tracy J. Muench and Miss Elizabeth A. Budde for their part in the work of reproducing the material, and Mr Charles B. Elston for making it possible for me to include in this book several illustrations from manuscripts at Marquette: the pages carrying sketches of Dunharrow, of the mountains at the head of Harrowdale, and of Kirith Ungol, the plan of Minas Tirith, and the full-page drawing of Orthanc (5).

This book follows the plan and presentation of its predecessors, references to previous volumes in 'The History of Middle-earth' being generally given in Roman numerals (thus 'VII'

refers to The Treason of Isengard), FR, TT, and RK being used as abbreviations for The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King, and page-references being made throughout to the three-volume hardback edition of The Lord of the Rings (LR). In several parts of the book the textual history is exceedingly complex. Since the story of the evolution of The Lord of the Rings can of course only be discovered by the correct ordering and interpretation of the manuscripts, and must be recounted in those terms, the textual history cannot be much simplified; and I have made much use of identifying letters for the manuscripts in order to clarify my account and to try to avoid ambiguities. In Books IV and V problems of chronological synchronisation became acute: a severe tension is sometimes perceptible between narrative certainties and the demands of an entirely coherent chronological structure (and the attempt to right dislocation in time could very well lead to dislocation in geography). Chronology is so important in this part of The Lord of the Rings that I could not neglect it, but I have put almost all of my complicated and often inconclusive discussion into 'Notes on the Chronology' at the end of chapters.

In this book I have used accents throughout in the name, of the Rohirrim (Theoden, Eomer, &c.).

Mr Charles Noad has again read the proofs independently and checked the very large number of citations, including those to other passages within the book, with a strictness and care that I seem altogether unable to attain. In addition I have adopted several of his suggestions for improvement in clarity and consistency in my account. I am much indebted to him for this generous and substantial work.

I am very grateful for communications from Mr Alan Stokes and Mr Neil Gaiman, who have explained my father's reference in his remarks about the origins of the poem Errantry (The Treason of Isengard p. 85): 'It was.begun very many years ago, in an attempt to go on with the model that came unbidden into my mind: the first six lines, in which, I guess, D'ye ken the rhyme to porringer had a part.' The reference is to a Jacobite song attacking William of Orange as usurper of the English crown from his father-in-law, James II, and threatening to hang him. The first verse of this song runs thus in the version given by Iona and Peter Opie in The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (no. 422):

What is the rhyme for porringer?

What is the rhyme for porringer?

The king he had a daughter fair

And gave the Prime of Orange her.

The verse is known in several forms (in one of which the opening line is Ken ye the rhyme to porringer? and the last And he gave her to an Oranger). This then is the unlikely origin of the provender of the Merry Messenger:

There was a merry passenger,

a messenger, an errander;

he took a tiny porringer

and oranges for provender.

PART ONE.

THE FALL OF

SARUMAN.

I.

THE DESTRUCTION OF ISENGARD.

(Chronology)

The writing of the story from 'The King of the Golden Hall' to the end of the first book of The Two Towers was an extremely complex process. The 'Isengard story' was not conceived and set down as a series of clearly marked 'chapters', each one brought to a developed state before the next was embarked on, but evolved as a whole, and disturbances of the structure that entered as it evolved led to disloca-tions all through the narrative. With my father's method of composition at this time - passages of very rough and piecemeal drafting being built into a completed manuscript that was in turn heavily overhauled, the whole complex advancing and changing at the same time - the textual confusion in this part of The Lord of the Rings is only penetrable with great difficulty, and to set it out as a clear sequence impossible.

The essential cause of this situation was the question of chronology; and I think that the best way to approach the writing of this part of the narrative is to try to set out first the problems that my father was contending with, and to refer back to this discussion when citing the actual texts.

The story had certain fixed narrative 'moments' and relations.

Pippin and Merry had encountered Treebeard in the forest of Fangorn and been taken to his 'Ent-house' of Wellinghall for the night. On that same day Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas had encountered Eomer and his company returning from battle with the Orcs, and they themselves passed the night beside the battlefield. For these purposes this may be called 'Day 1', since earlier events have here no relevance; the actual date according to the chronology of this period in the writing of The Lord of the Rings was Sunday January 29 (see VII.368, 406).

On Day 2, January 30, the Entmoot took place; and on that day Aragorn and his companions met Gandalf returned, and together they set out on their great ride to Eodoras. As they rode south in the evening Legolas saw far off towards the Gap of Rohan a great smoke rising, and he asked Gandalf what it might be: to which Gandalf replied 'Battle and war! ' (at the end of the chapter 'The White Rider').

They rode all night, and reached Eodoras in the early morning of Day 3, January 31. While they spoke with Theoden and Wormtongue in the Golden Hall at Eodoras the Entmoot was still rumbling on far away in Fangorn. In the afternoon of Day 3 Theoden with Gandalf and his companions and a host of the Rohirrim set out west from Eodoras across the plains of Rohan towards the Fords of Isen; and on that same afternoon the Entmoot ended,(1) and the Ents began their march on Isengard, which they reached after nightfall.

It is here that the chronological problems appear. There were - or would be, as the story evolved - the following elements (some of them foreseen in some form in the outline that I called 'The Story Foreseen from Fangorn', VII.435 - 6) to be brought into a coherent time-pattern.

The Ents would attack Isengard, and drown it by diverting the course of the river Isen. A great force would leave Isengard; the Riders at the Fords of Isen would be driven back over the river. The Rohirrim coming from Eodoras would see a great darkness in the direction of the Wizard's Vale, and they would meet a lone horseman returning from the battle at the Fords; Gandalf would fleet away westwards on Shadowfax. Theoden and his host, with Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas, would take refuge in a deep gorge in the southern mountains, and a great battle there would turn to victory after certain defeat with the coming of the 'moving trees', and the return of Gandalf and the lord of the Rohirrim whose stronghold it was. Finally, Gandalf, with Theoden, Aragorn, Gimli, Legolas and a company of the Riders would leave the refuge and ride to Isengard, now drowned and in ruins, and meet Merry and Pippin sitting on a pile of rubble at the gates.