The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage (2 page)

Read The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage Online

Authors: Jan Morris

Tags: #Mediterranean Region, #Venice (Italy), #History, #General, #Europe, #Italy, #Medieval, #Science, #Social Science, #Human Geography, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues

But at the same time Venice depended upon the Muslim trade. Her relationship with Islam was always ambiguous. Though she

took part in more than one Crusade, she hung on to her trading stations in Syria and Egypt: even while she fought the Turks, she maintained her commercial contacts within their territories, and at the height of the antagonism indeed allowed Turkish merchants to establish their own business centre on the Grand Canal in Venice. However appallingly the Turks used her, she was generally swift to appease them. While she represented herself to the west as the lonely champion of Christendom, to Islam she liked to appear as a sort of neutral service industry: when in 1464 some Muslim passengers were seized from a Venetian ship by the militantly Christian Knights of St John, at Rhodes, within a week a Venetian fleet arrived off the island, an ultimatum was delivered, the Knights were overawed, and the infidels were delivered safely to Alexandria with fulsome hopes, we may assume, of continuing future favours.

The Venetian Empire was a parasite upon the body of Islam, but as the centuries passed this became an increasingly uncomfortable status. If the Venetians needed Islam, Islam did not greatly need Venice, and in four fierce wars and innumerable skirmishes the Turks gradually whittled away the republic’s eastern possessions. One by one the colonies fell, until at the moment of Venice’s own extinction as a state, in 1797, she had nothing much left but the Ionian Islands, off the coast of Greece, and a few footholds on the eastern shore of the Adriatic – properties useless to her anyway by then, except as reminders of the glorious past.

Venice was never

primarily

an imperial power, and her surpassing interest to historians and travellers of all periods has been only indirectly due to empire. As we make our own journey we must remind ourselves now and then of the great things always happening at the imperial capital far away. The city itself gradually reached the apex of its magnificence as the most luxurious place in Europe – La Serenissima, The Most Serene Republic – and the Venetian constitution was refined into the subtle and watchful oligarchy, under its elected Doges, that was the wonder of the nations. The Venetian bureaucracy was developed into a mighty instrument of power and permanence. For a century a vicious war was waged against the most persistent of Venice’s European

rivals, Genoa, culminating in a dramatic final victory actually within sight of the city. The mainland estate, the

terrafirma

, was created and consolidated, while repeatedly Venice was drawn into the vast dynastic and religious conflicts of the rest of Europe. More than once the republic was formally excommunicated by the Pope for its heretical tendencies. Several times it was decimated by plague. A succession of great artists brought glory to the city: a slow enfeeblement of the national will eventually brought it ignominy.

For like all states, the Venetian Republic waxed and waned. It reached the apogee of its reputation, perhaps, in the fifteenth century, but its decline was protracted. The stalwart character of the people imperceptibly softened. The integrity of the ruling nobles was corroded by greed and self-indulgence. The rise of superpowers, the Ottoman Empire to the east, the Spanish Empire to the west, put Venice, whose population never exceeded 170,000, out of scale in the world: the more progressive skills of northern mariners, Dutch and Engl∗∗∗ish, outclassed her on her native element, the sea. New political organisms, new ideas and energies left the republic an anachronism among the nations of Europe: until at last in 1797 Napoleon Bonaparte, declaring, ‘I will be an Atilla to the Venetian State’, sent his soldiers into the lagoons and put an end to it all, to the glory of progress and the sorrow of romantics everywhere. Wordsworth spoke for them all, in the heyday of Romanticism, when he wrote his sonnet, ‘On the Extinction of the Venetian Republic’:

Once did She hold the gorgeous East in fee:

And was the safeguard of the west: the worth

Of Venice did not fall below her birth,

Venice, the eldest Child of Liberty.

She was a maiden City, bright and free;

No guile seduced, no force could violate;

And, when she took unto herself a Mate,

She must espouse the everlasting Sea.

And what if she had seen those glories fade,

Those titles vanish, and that strength decay;

Yet shall some tribute of regret be paid

When her long life hath reached its final day:

Men are we, and must grieve when even the Shade

Of that which once was great, is passed away.

All this we should keep at the corner of our mind’s eye, then, as we sail the sunlit seas, clamber the flowered fortress walls, admire the heroes and deplore the villains of the

Stato da Mar:

and I have included a chronological table too, after the gazetteer, to try and put our voyage into historical perspective. These islands, capes and cities of the sea were distant reflections of a much greater image. It is only proper that we start our journey through them, as we shall end it, in the very eye of the sun, on the brilliant and bustling waterfront before the palace of the Doges.

Prospects from the Piazzetta – a very

particular city – come of age – a pious

commitment – setting sail

T

he

most

glittering

of all the world’s belvederes, the most suggestive of great occasion and lofty circumstance, is surely the Piazzetta di San Marco, the Little Piazza of St Mark, upon the waterfront at Venice. Two marble columns stand in it, one crowned with a peculiar winged lion of St Mark, the city’s patron saint, the other with a figure of St Theodore, his predecessor in that office, in the company of a crocodile: and if you stand between the two of them, where they used to hang malefactors long ago, you may feel yourself almost to be part of Venice, so infectious is the spirit of the place, and so vivid are all its meanings.

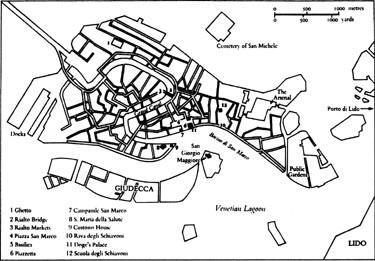

Immediately behind you is stacked the ancient fulcrum of the city: the pinkish mass of the Doge’s Palace, the arcane gilded domes of the Basilica beyond, the towering Campanile with the angel on its summit and the sightseers thronging its belfry, the arcaded elegance of the Piazza San Marco, Napoleon’s ‘finest drawing-room in Europe’, from whose recesses, if the season is right, the wistful strains of competing café orchestras sigh and thump above the murmur of the crowd. To the west, beyond the golden weather-vane of the Customs House (held by a figure of Fortune and supported on its great sphere by two muscular Atlases), the Grand Canal sweeps away between an avenue of palaces towards the Rialto. To the east the Riva degli Schiavoni disappears humped with bridges and lined with hotels past the ferry-boats, the tugs and the cruise-liners at their berths towards the distant green smudge of the Public Gardens.

Venice

Venice

Immediately in front of you, the ever shining and shifting proscenium of this theatre, lies the Bacino di San Marco, the Basin of St Mark, for a thousand years the grand harbour of Venice. It is dominated from this viewpoint, as by some monumental piece of stage scenery, by the towered island of San Giorgio Maggiore, and it is streaked around the edges with mudbanks when the tide is low, and speckled, as it opens into the wide lagoon, with the hefty wooden tripods that mark the deep-water passages out to sea.

Night and day the ships go by. Sometimes a great freighter passes, hugely out of proportion, its riggings, aerials and radar-scanners gliding away queerly through roofs and chimney-pots towards the docks. Sometimes a cruise ship prances in. Ever and again there come and go the indomitable

vaporetti

, the water-buses of Venice, deep in the water with new arrivals from the railway station and the car parks, and sometimes the yellow-funnelled Chioggia steamer hoots, shudders a little, backs away from her moorings and sets off into the lagoon. The gondolas, if it

is the tourist season (for gondolas nowadays tend to be hibernatory craft) progress languidly here and there, a flutter of ribbons from gondoliers’ straw hats, a trailing of honeymoon fingers over gunwales. Portentous official launches hasten from office to conference. Speedboats of the rich speed away to the Lido or Harry’s Bar. A grey customs launch detaches itself with a bellow from its berth beyond San Giorgio and ominously roars off in pursuit of contraband (or possibly lunch).

It is a restless scene. The ships are never satisfied, the tourists mill and churn. The water itself has no surf or breakers, but often seems to be chopped, in a peculiarly Venetian way, into a million little particles of light-reflecting vapour, rather like ice-fragments, giving the surface of the lagoon a dancing, prismatic quality. The Piazzetta is never static, never silent, and never empty of life: it has been in this condition, night and day, since the early Middle Ages, and every now and then it has been the setting of one of those spectacular displays of pageantry and purpose which have always been essential to the style of Venice.

Captains-General of the Sea, for example, have set off with their squadrons for distant campaigns. Enormous regattas have celebrated holy days or victories. Visiting potentates or holy men have been welcomed. In 1374 Henry III of France sailed in on a ship rowed by 400 Slavs, with an escort of fourteen galleys, a raft upon which glass-blowers created fanciful objects from a furnace shaped like a marine monster, an armada of fantastically decorated floats circling all around, and a welcoming arch designed by Palladio and decorated jointly by Tintoretto and Veronese. In 1961 Queen Elizabeth II of England arrived in her royal yacht, while from the gun-turret of her escorting destroyer a solitary Scottish piper, kilts swirling in the breeze, head held high like cock-o’-the-walk, played a proud if inaudible Highland melody. I myself have seen a dead Pope come in, golden-masked and gilt-coffined on the poop of a ceremonial barge, to a heavy swish of oars and the rhythmic beat of a galley-master’s drum.

On 8 November 1202, ‘in the octave of the Feast of St Remigius’, one such spectacle, never to be forgotten by the Venetians, began the transformation of their city-state into a maritime empire: for on that fine day of a St Martin’s summer the

octogenarian and purblind Enrico Dandolo, forty-first Doge of Venice, boarded his red-painted galley in the Basin, beneath a canopy of vermilion silk, to trumpet calls, priestly chanting and the cheers of a mighty fleet lying all around, and set in motion the events of the Fourth Crusade – which were presently to make him and all his seventy-nine successors, at least in name, Lords of a Quarter and a Half-Quarter of the Roman Empire.

Venice had been in existence for some five hundred years already. Born out of the fall of Rome, when her first rickety townships were built within the fastness of the lagoon, she had become a client of the Byzantine Empire, which had its headquarters in Constantinople, alias Byzantium, now Istanbul, and was the eastern successor to Rome’s glories. Through the first centuries of their history, while much of western Europe endured the Dark Ages of barbaric regression, the Venetians had organized their affairs within the fold of Byzantine power. Sometimes they availed themselves of Byzantine protection, sometimes they acted as mercenaries for Byzantium, and so loyal had they been to the suzerainty that one of the more fulsome of the emperors had called Venice ‘Byzantium’s favourite daughter’.

In 1202, accordingly, this was in many respects a Byzantine city, though of a very particular kind. The impact it had upon strangers was much the same then as now: the marvellous spectacle of a city built upon mudbanks, its walls rising directly out of the lagoon, was perhaps even more astonishing in those days, when laborious journeys over the wild Alps, or perilous voyages through the Mediterranean, deposited the stranger at last upon this marvellous strand. The earliest townscape picture we have of Venice, a fourteenth-century miniature in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, seems to have been painted in a kind of daze: fantastically coloured domes and turrets crown the scene, suave white swans float around, and a sightseer in the Piazzetta is looking up at the lion on its column in just that attitude of disjointed bemusement in which, any summer day, you may see amateur cameramen aiming themselves at the animal now.

It was a city of about 80,000 people, one of the biggest in Europe, and it was organized by parishes, each with its own

strong character, its own social hierarchy, so that there was no rich quarter of town, and no poor. It was mostly built of wood, but its functional shape had already been evolved – that sensible, machine-like pattern which modern town-planners so admire. The waters all around it meant that it need not be circumvallated, but a wall protected the city on its seaward side, and the principal buildings were mostly defensive in style. This gave it a very

jagged

look: for besides the big pot-bellied chimney-pots which crowned every house, there were embattlements everywhere, and in particular a twin-pronged kind of merlonation, slightly oriental of cast, which seemed to run along the tops of everything, and pungently accentuated the exotic nature of the place.