The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage (10 page)

Read The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage Online

Authors: Jan Morris

Tags: #Mediterranean Region, #Venice (Italy), #History, #General, #Europe, #Italy, #Medieval, #Science, #Social Science, #Human Geography, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues

Poor Canale! If he was scarcely a Nelsonic sailor, he was a man of culture and discrimination, a scholar, an experienced diplomat. In this he was not unusual among the admirals of the Venetian fleet. The Venetian system of oligarchic responsibility meant that while the Republic’s sea-commanders were always noblemen, they were not always professional seamen, and although this led sometimes to humiliation, it produced also, over the centuries, some very remarkable captains to lead the flotillas of Venice through the eastern seas. Let us, while we recover from the horrors of Khalkis, and try to forget the disjuncture of poor Erizzo on his planks, take a look at a few of them.

Another eminent amateur was Antonio Grimani, Captain-General later in the fifteenth century. He was a highly successful financier and a skilled negotiator, the father of a Cardinal and a great man in Venice, but like Canale, no genius as an admiral. Having lost a particularly crucial engagement against the Turks, he too was sent home in irons (one of them fastened to his leg, as a special favour, by his own son). In Venice he was greeted as a traitor, lampooned in popular ballads as ‘the ruin of the Christians’, and exiled for life to the Dalmatian island of Cres, but he arranged matters better than Canale. He escaped to Rome, and so cannily organized his reconciliation with Venice that in 1521 he was elected to the Dogeship, eighty-five years old, and officially described, so many years after his disgrace at sea, as serene, excellent, virtuous, worthy, and giving great hope for the welfare and preservation of the state.

Vettore Pisani, on the other hand, Captain-General during the fourteenth-century wars against Genoa, was everybody’s idea of

a sea-dog, beloved of his men, contemptuous of authority, always ready for a fight. He was ‘the chief and father of all the seamen of Venice’. Arrested and charged after a defeat at Pola, in Istria, in 1379, he was spending six months in the dungeons when the Genoese took Chioggia, at the southern edge of the lagoon, and threatened Venice herself. The seamen of Venice declined to fight without him, and 400 men arriving from the lagoon towns specifically to serve under him threw down their banners and went home again – using, so their chronicler says, language too dreadful to record. So they let Pisani out. ‘

Viva

Messer Vettore!’ cried the adoring crowd as he emerged from the prisons, but he stopped them. ‘Enough of that, my sons,’ he said, ‘shout instead

Viva

the Good Evangelist San Marco!’ – and so he went to sea again, and rallied the fleet, and beat the Genoese, and saved Venice, and died in action like the hero he was.

His great peer and contemporary was Carlo Zeno, a very different character. Intellectual, statesman, fighting man, a knowledgeable scientist, a devoted classical scholar, a buccaneer and a showman, Zeno played a multitude of roles in a life full of excitement. We see him as a theological student at Padua, a young curé at Patras in Greece, a merchant on the Golden Horn, Bailie of Euboea. We see him as the most dazzling of galley commanders: burning Genoese ships all over the eastern Mediterranean, sending whole cargoes of loot to be auctioned in Crete, seizing in Rhodes harbour the greatest prize of all, the

Richignona

, the largest Genoese ship afloat, with a cargo worth half-a-million ducats and a complement of 160 rich and highly ransomable merchants.

Finally we see him, in the theatrical way he loved, appearing with his fleet before Chioggia just in time to join Pisani in the salvation of Venice from the Genoese. Zeno was imprisoned for conspiracy once, and once failed by only a handful of votes to become Doge of the Republic. He was scarred all over from his innumerable sea-battles, but he kept his eyesight until the end, never wearing spectacles in his life. They buried him, as was proper, near the Arsenal that built his ships for him, and somewhere there, lost under new dockyard buildings down the years, his grand old bones still rot.

Vittore Cappello, in the fifteenth century, was so disturbed by a

series of reverses in Grecian waters that he was not seen to smile for five months, and died of a broken heart. Benedetto Pesaro, in the sixteenth century, kept a mistress on board his flagship until he was well into his seventies, and habitually beheaded insubordinate officers of his fleet, while his kinsman Jacopo Pesaro was not only an admiral, but Bishop of Paphos too. Cristofero da Canale wrote a book about naval administration in the form of an elaborate imaginary dialogue and took his four-year-old son to sea with him, claiming to have weaned him on ship’s biscuit. Francesco Morosini, whom we shall meet again, dressed always in red from top to toe and never went into action without his cat beside him on the poop.

Such were the remarkable characters who commanded the fleets of Venice. They lost battles almost as often as they won them, they could be cowardly as well as heroic, venal as well as high-minded. Few of them, though, sound ordinary men, and it must have made pulses beat a little faster, brought history itself a little closer, when one of these magnificos swept into harbour beneath his gold-embroidered standard, and stepped ashore upon the modest waterfront of Mykonos or Kea.

But even the admirals could not hold the Aegean for Venice. The loss of Euboea did not mean, as Cassandras forecast at the time, the loss of the whole empire, Cyclades to Istria, but it did deprive Venice of her chief base in the Aegean, and one by one the other islands fell to the Turks.

It was a slow and awful process, extended over 200 years. Sometimes the squeeze was squalid – the demand for protection money, for example, collected by implacable Turkish captains island by island. More often it was horrific. For generations the Aegean was terrorized by Turkish raiders: ports were repeatedly burned, islanders were seized in their thousands for slavery or concubinage, whole populations had to shut themselves up each night within fortress walls. The terrible corsair Khayr ad-Din, ‘Barbarossa’, when he raided an island, killed all the Catholics for a start. He then slaughtered all the old Greeks, took the young men as galley-slaves and packed away the boys to Constantinople. Finally, making the women dance before him,

he chose the best-looking for his harem, sharing out the rest among his men according to rank, until the ugliest and oldest of them all were handed over to the soldiery.

The Aegean islands were the most exposed outposts of Christianity against the advance of Islam, but by the sixteenth century Venice was clearly powerless to save them, and the other powers of Europe would do nothing to help. Duke Giovanni IV of Naxos appealed directly to the Pope, the Emperor Charles V, Ferdinand King of the Romans, François I of France ‘and all the other Christian kings and princes’, but it did no good, and he became virtually a puppet of the Turks.

Desolation crept over the islands, and the more remote of them were almost empty of life. There were virtually no men at all, reported a fifteenth-century traveller, on the island of Sifnos; at Serifos the people lived ‘like brutes’, terrified night and day of Turkish raiders; the islanders of Syros lived only on carobs and goat flesh, while at Ios the farmers did not dare to leave the castle ramparts until old women had crept out in the dawn to make sure there were no Turks about. The lights faded in the

pirgoi

, the choirs no longer sang in the little island cathedrals, and one by one, almost organically, by assault or default the Venetian possessions of the Aegean dropped into the hands of the Turk.

By the last years of the seventeenth century everything was lost, except only the island of Tinos in the Cyclades. The Greek islanders had often betrayed their Catholic masters to the Turks, but this was one place where many of them had been converted to Catholicism themselves – other Greeks called it ‘the Pope’s island’. They were intensely loyal to the Signory, and so it was that when Euboea had been Turkish for 250 years, when the Duchy of the Archipelago was no more than a romantic memory, little Tinos, all 200 square miles of it, still bravely flew the flag.

The Republic could not take much credit for this, for it had neglected the island disgracefully. Tinos had come under direct Venetian government in 1390 by the bequest of its feudal lord, descendant of one of Sanudo’s men, but the Venetians were not anxious to be saddled with it. They auctioned a lease on it at first. Later they acceded to the appeals of its inhabitants, who had suffered greatly from their feudal masters (one of them had tried

to deport them all to another underpopulated island he happened to possess), and who declared in a petition to the Signory that ‘no lordship under heaven is as just and good as that of Venice’. For three centuries a Venetian Rector governed the island, and the Venetian fleet intermittently protected it.

Intermittently, because here as everywhere they never did succeed in keeping Turkish raiders off. Time after time ferocious Muslim generals landed on the Tinos foreshore, burning villages and killing everyone in sight. They seldom stayed for long, though, and were often sent off in ignominy. Once a passing Turkish admiral sent a message to the Rector demanding the instant payment of a heavy tribute, in default of which the entire island would be laid waste by fire. The Rector replied that the Pasha had only to come and get it, but when the Turkish galleys entered the port, instantly their crews were fallen upon by a thousand Tiniots, led by the Rector in person, and humiliatingly beaten back to their ships. Tinos acquired a reputation for unwavering resolution, and was much praised in the reports and chronicles of the Venetians – ‘a rose among thorns’, as one writer picturesquely put it, surveying the ever pricklier prospect of the Aegean. (Besides, they very much liked its onions, which were eaten raw, like apples, and which were claimed to be odourless.)

The Tiniots themselves were no less proud of their loyalty, and to this day Tinos remains one of the most Catholic islands of the Greek archipelagos. This is piquant, for it is also the Lourdes of Greek Orthodoxy. In 1824 a miraculous icon of the Virgin was found buried beneath a chapel on the island, and a powerful cult grew up around it, with popular pilgrimages twice each year. Thousands of people come out for the day from Athens, and hundreds of sick are brought to be cured. On the Feast of the Assumption in 1940, when the place was crowded with pilgrims, the Greek cruiser

Helle

was torpedoed in the harbour, presumably by an Italian submarine, and this tragedy has become curiously interwoven with the story of the icon itself, so that models of the warship (which was built in America for the Chinese navy) are sold everywhere among the

ex votos

and holy pictures, arousing a powerfully emotional association of ideas.

At first, then, even on an ordinary weekday, Tinos feels

anything but Venetian. The big white pilgrimage church above the town is patrolled by bearded tall-hatted priests. Crowds of black-shawled women move in and out of the shrine. Through the open doors of the icon’s chapel you may glimpse that mystery of candles, incense, gleaming silver things, swarthy ecstatic faces, shadows and resplendences that is the essence of the Orthodox style. The long, wide highway to the church is lined with booths and pilgrim hostels, and every other souvenir is stamped, somehow or other, with the image of the icon. Attended by these holy events, busy always with the ferry-steamers, the motor-caiques, the speedboats, the visiting yachts and the rumbling motor-gunboats of the Hellenic seas, Tinos town is pure, almost archetypically Greek. Only the fancifully decorated dovecotes on the edge of town, like so many pastry-houses, remind one that the Venetians, with their taste for the frivolous and the extravagant, were ever here at all.

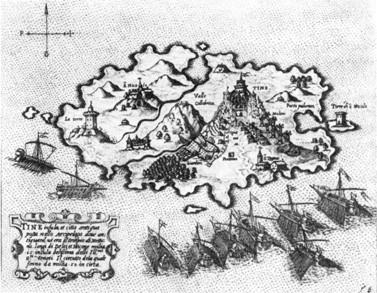

It is in the countryside behind that you can still get in touch with them. The Catholic archbishop, successor to a long line of Venetian incumbents, tactfully has his palace in the inland village of Xynara, well away from the holy icon, and the Venetians themselves, in their days of power, established their headquarters away from the water’s edge. From a boat off-shore you can see the pattern of their settlement. To the left of the modern port a mole and a couple of ruins mark the site of their harbour; inland, white villages with Italianate campaniles speckle the countryside like exiles from the Veneto; and over the shoulder of the town, clinging to the sides of an almost conical mountain peak, you can just make out the remains of the Venetian colonial capital, their very last foothold in the Aegean Sea, Exombourgo.

Not much is left of it. In its great days it was something of a wonder, and the old prints, prone to licence though they are, suggest its spectacular character. The peak, which is actually 1,700 feet high, looks excessively tall, steep and sudden in these high-spirited old versions, and towers like an Everest over the island: and perched dizzily on its summit, like an outcrop of the rock itself, the fortress of Santa Elena stands in a positive eruption of towers, walls and flags. Apparently impregnable ramparts circle the peak, and below it the island seems to lie trustful and

Tinos

Tinos

secure, characterized by benign farmsteads and peacefully anchored ships.