The Unknown Warrior (15 page)

Read The Unknown Warrior Online

Authors: Richard Osgood

The relatively new discipline of battlefield archaeology has much to commend it in evaluating the flow of battles, troop movements and formation positions. It can also illustrate the weaponry used and elements of the lives of the soldiers in those violent hours of combat (Pollard and Oliver, 2002, 2003), providing information often not available to the historian. Much of our information derives from two mass graves, one at Towton, North Yorkshire, and the other at Visby (formerly Wisby), on the Baltic island of Gotland. Mass graves are the more likely resting place for the common soldier with gentry being afforded, even in death, greater respect (Strickland and Hardy, 2005: 280).

At Towton, a mass burial of footsoldiers killed on 29 March 1461 in a most bloody Wars of the Roses encounter has been particularly illuminating in terms of giving us an understanding of the many elements of the soldiers involved. Some of these men were young (16â25 years old), others were up to

c.

50 years of age, with an average of around 30 years (Boylston, Holst and Coughlan, 2000: 52) â compare this with the average age of 19 for the American infantryman in the Vietnam War in the twentieth century.

At Visby, in the summer of 1361, a large Danish force of King Waldemar fought and defeated the town's forces. Old and young, able-bodied and disabled were killed in the heat of a July day and the town fell to the Danes. Although the local troops were wearing armour, these were outmoded pieces and failed to prevent their defeat. As the bodies rotted in the sun, the armour probably became irretrievable and was cast with the bodies into a series of mass graves, graves which were discovered by archaeologists in the twentieth century.

Some traces of the infantryman on major battlefields of the period have yet to be found archaeologically. Will it ever be possible to locate the stake holes of the timber spikes driven into the ground by English infantry at Agincourt (1415) to ward off the French cavalry? Or to find the ditch dug at Crécy (1346), again by the English, who, according to the chronicler Geoffrey le Baker, âdug many holes in the earth in front of our first line, one foot deep and one foot wide, so that if it happened that the French cavalry were able to attack them, the horses might stagger because of the holes' (de Vries, 1998: 164)?

This chapter puts forward some of the evidence we have for material from the sites of conflict, material showing the very real aspects of fighting rather than the showy aspects of display demonstrated in the âage of chivalry'.

WEAPONRY

Weaponry and armour from the Medieval period can be seen in many museums, castles and stately homes throughout the world; what we are particularly concerned with for the purpose of this study are those items that have left a trace in the archaeological record; of weapons and armour found on battle sites, and of clearly discernible weapon damage to equipment or the victims of conflict.

As in the earlier chapters, there are problems finding material from ancient battlefields when small items suffer the corrosive effects of time and are subject to unreported chance finds. Given the ferocity of the engagement at Agincourt, for example, one might have expected to find more than the one possible bodkin arrowhead revealed in a recent survey (Wason, 2003: 60). Perhaps the majority of armour was stripped from the dead and the arrows retrieved, or maybe material has been taken over the years. It is possible that the site is located slightly further from the area traditionally denoted, or perhaps the site simply needs more work. The archaeologist Tim Sutherland has undertaken a geophysical survey that might suggest more finds in the future on this battlefield â with a tantalisingly large anomaly being found on his geophysical survey close to the nineteenth-century crucifix commemorating the dead of the battle and supposedly marking the site of the French burial pit (

ibid.

: 65).

Tom Richardson of the Royal Armouries, Leeds, believed that the concentration of head wounds to the Towton skeletons, and relative lack of body wounds, might indicate a lack of head protection; perhaps the simple discarding of armoured headgear such as a

sallet

to enable a quicker flight from the battle. The wounds at Towton illustrate the variety of weapons in use against the infantry. Of these wounds, many seem to have been inflicted from the front by right-handed assailants. On twenty-seven of the twenty-eight crania there was evidence for perimortem trauma â 32 per cent of wounds on occipital, 32 per cent on frontal, and 31 per cent on left parietal bones (Novak, 2000a: 95). The types of wounds ranged from blade to crush to puncture. It was difficult to distinguish the type of weapon responsible for cut wounds â these could have been caused by poleaxe blade, sword or dagger. Perhaps the same can be said for crush wounds â war hammer, mace, sword-pommel â and for puncture wounds â longbow arrows, crossbow bolts. However, as the latter category of wounds âwere so distinct in shape and size, cross matching with weapons from the battle was attempted' (

ibid.

: 97). This was accomplished using weapons held in the collections of the Royal Armouries.

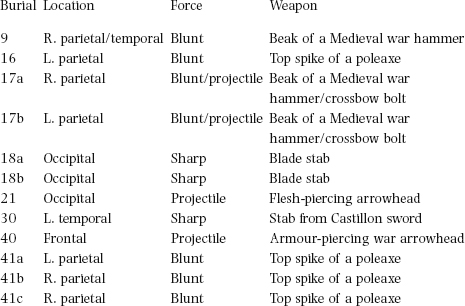

Table 4.1.

Towton puncture wounds classification

Source

: Novak (2000a: 98).

Although these wounds are those suffered by rather than inflicted by Medieval infantrymen, it nonetheless helps to reveal the range of weapons that our study set was up against. From the puncture wounds alone they seem to have faced cavalry as well as infantry. The study was enough for Novak to state that âwhat we are seeing is merely the result of hand-to-hand combat in a brutal battle using very efficient weapons of war' (

ibid.

: 100â1). Surveys of this battlefield have also yielded weapons, including sword scabbard chapes and, through a measured ferrous metal survey, several bodkin arrowheads (Sutherland, 2000b: 160â2).

Arrowheads have been found on several excavations of Medieval sites. One example is at Urquhart Castle on Loch Ness, Scotland. Work here uncovered bodkin heads of varying lengths, three heads with broader cutting edges and a possible crossbow bolt head. In addition, a corroded mass proved to be a group of arrowheads that were once probably stored in a canvas or fabric bag, but which are now rusted together (Strickland and Hardy, 2005: 176). Arrowheads of the Medieval period have been found at Portchester Castle, on the south coast of England, and were probably for use by the garrison. These included some from the thirteenth century, varying in form from heavy arrows with barbs and socket to those with flat blades. Several crossbow bolts were also excavated (Hinton, 1977: 198â9).

As expected, archaeology often confirms what is known historically. For example, work at Gorey (Mont Orgueil) Castle in Jersey has uncovered a number of crossbow bolt heads dating from around 1460. Documentary evidence for this site suggested that this castle was provided with a garrison of up to forty-four crossbowmen (Watts and Mahrer, 2004: 55).

It is a commonly held belief that the presence of yew trees in English churchyards was for provision of wood vital for the construction of the longbows that were the mainstay of the Medieval infantryman. Contrary to this belief, King Henry V expressly forbade timber being taken from ecclesiastical land for this purpose (Strickland and Hardy, 2005: 16).

In terms of offensive weapons found at Visby, several iron arrowheads were recovered, along with iron knives and a possible pike head (Thordeman, 2001: 134â5). Furthermore, several skulls, transfixed with crossbow bolts fired by Danish troops, seem to indicate that both horizontal fire at close quarters and enfilade fire (resulting in wounds on both sides of the skull) were used. From the evidence, it seems as though crossbows were more in evidence on the field of Visby than at Towton. As with all battlefields, much of the equipment was recoverable by the victors and thus the archaeological record is unlikely to retain large quantities of valuable equipment unless, of course, its damage had rendered it useless or it was embedded in a corpse. The skeletons themselves indicate a number of types of weapons used, from sword and axe blades to the circular craters left on skulls by clubs (Ingelmark, 2001: 190â1).

Towton and Visby mass burials illustrate the vast range of Medieval weapon types through the form of the damage they inflicted. Manchester has found an example of the use of another weapon that could cause huge crush injuries. One of the most malicious hand weapons of all time was the medieval âmorning star' or âholy water sprinkler'. This flailing implement featured protruding metal spikes. âA flail such as this in the hands of country peasants, who were accustomed to using it, must have been a terrifying weapon which could bash the finest helmets of the crusaders to smithereens.' An example of a depressed skull fracture caused by such a weapon has been described from the Sedlec Ossuary, Czechoslovakia [

sic

] and dated to the Hussite Wars of the fifteenth century' (Manchester, 1983a: 60; see also Courville, 1965).

Pollard and Oliver (2002: 54) have located several items relating to the infantryman's panoply of arms in their examination of a series of British battlefields. At the site of the Battle of Shrewsbury (1403), several arrowheads were found â including a probable âbodkin' arrowhead â which were long, narrow and designed to punch through armour. These arrowheads had proved their worth for the English against mounted knights at the battles of Crécy and Poitiers (1356), as part of the Hundred Years War, and the bowmen would again show their might in 1415, at Agincourt.

The use of swords, pole arms and bows and arrows forms only part of the picture, representing finds that have been made through archaeology. As we have seen in previous chapters, environmental conditions will have affected our assemblage and, in particular, the survival of materials such as wood and leather; clubs and staves may well have been available to the common soldier, but are now no longer visible.

ARMOUR

âThe men-at-arms, however, formed only a small proportion of the troops on a Wars of the Roses battlefield, and the equipment of the ordinary infantry, who formed the vast majority of these armies, is much more poorly understood and has received relatively little attention' (Richardson, 2000: 143). If this is so, our understanding of the armour worn by the common soldier in Medieval times is helped by the finds from mass graves, the wounds suffered by the deceased (indicative, perhaps, of areas of the body which were poorly protected) and of finds of armour itself.

Perhaps the head wounds inflicted on those whose bodies lay in the burial pit at Towton would indicate that there were failings in the efficacy of the head armour, unless, as has been said, the helmets were discarded as the troops fled. A small quantity of copper-alloy mail was found on the field of Towton (Sutherland 2000b: 160), but we must turn to Visby for clearer evidence of armour used in combat in the fourteenth century.

Possibly as a result of the putrefaction of the deceased, not all the armour was stripped from the bodies of the defeated peasant army at Visby. Men were cast into the grave pits wearing their mail shirts and coifs, with plate armour and gauntlets and even iron shoes still in place. This armour was almost certainly out of date by the standards of 1361, and had probably been handed down through families.

From the work at Visby it is possible to discern a series of types of protection worn by the combatants (for examples of these armour types, see Thordeman, 2001). The best-known pieces are the mail âcoifs', a type of hood worn to protect the head, constructed from bronze and from iron rings. Some of these hoods still encased the skulls of those who were wearing them when they died and one was worn by an elderly man, indicating the irregular nature of the force defending the town (Thordeman, 2001: 168). Although the excavators also found several lumps of rusted mail that might once have served as gauntlets, shirts or breeches, they felt confident to state that approximately 185 coifs were recovered from the graves (

ibid.

: 99). These took a similar form, being âprovided with a collar drooping down over the shoulders, and with the opening for the face straight at the top and rounded at the bottom, this opening being so small that the forehead, chin and greater part of the cheeks were protected' (

ibid.

: 104).

When discovered on a body that was also clad in armour, the coif was tucked inside the reinforced coat (

ibid.

: 106). No helmets were found in the grave pits and it is likely that this mail formed the only head protection â that is unless the putrefaction that despoiled the corpses, and thus the mail, had less effect on the overlying helmets and they were retrieved. If this was the case, one might expect the other types of armour to have been taken.

In addition to the mail coifs, two mail shirts were found â each covering the body of the man who died in it. The first shirt (Regn. no. Vxx 6) was quite short, with only a

c.

31cm length surviving, with the sleeves ending in a mail gauntlet â one of two found at Visby. The second example (Regn. no. Vss 13) was in better condition and found on a man who lay on his back in the grave. This shirt was around 1.45m wide at the base and probably around 50â54cm long (

ibid.

: 106â11).