The Unknown Warrior (14 page)

Read The Unknown Warrior Online

Authors: Richard Osgood

The man had suffered other wounds before death; a depressed fracture to the left malar bone that had removed the crown of an embedded left upper canine tooth and had damaged the left upper incisor at the same time. This was probably caused by a fairly major facial blow (Johnston

et al.

, 1980: 47). In death, the man was provided with a grave good for the afterlife â a shark's tooth that might have been worn as some sort of amulet. The tooth may have come from a Mako shark, of up to 100kg weight, probably retrieved from a dead specimen that had washed up on the shore (

ibid.

: 38, 43). So we are left with an individual buried with a grave good in a round barrow with a sword cut to the head and older, healed wounds.

Therein lies a problem: though the man was killed with a sword, was he killed in battle, murdered, sacrificed or executed? Perhaps the Sutton Veny man was unlikely to have been an executed criminal given that he had a grave good, but it is impossible to be too dogmatic based on the surviving evidence and thus it is always important to bear in mind the possibility for differing scenarios for the final moments of those with weapon injuries when examining the archaeological record.

Executions also leave skeletons with weapon trauma and archaeologists must be careful to consider this when asking questions of wounds in the archaeological record. One such Anglo-Saxon skeleton, from Stonehenge, Wiltshire, is that of a 28â32-year-old man who had died between 600 and 690. He was probably around 1.65m in height and had been decapitated with a single blow delivered from the rear right (McKinley and Boylston, 2002: 136â7). There are several sites that seem to suggest judicial execution in this period (Reynolds, 2002a: 105â10).

Other Anglo-Saxon burials with trauma have been located in excavations in Britain. The body in Grave 1 at Puddlehill, Bedfordshire, was âassumed to have been killed by a sword blow, as there were severe unhealed cranial injuries. The youth with a sugar-loaf shield-boss, spearhead and knife from Ewell, Surrey, had lost his left foot before death' (Lucy, 2000: 68) â but the latter case may not have been related to warfare. More convincing was a male skeleton from Harwell, Oxfordshire (Body G7), with a spear embedded in his left side (

ibid.

: 68â9) and a male from Letchworth, Bedfordshire, with a spearhead embedded in his chest (Kennett, 1973: 103). In addition to these, a large male skeleton with an iron javelin head transfixing his pelvis was excavated at Cross Hands, Compton, Berkshire (Peake, 1906: 279).

Excavations at St Andrew's Church, Fishergate, York, have also produced several burials that display combat wounds. Not all are contemporary and some, as we shall see in

Chapter 4

, have led at least one author to suggest that they may indicate the presence of âtrial by combat'. This being said, twelve males who were excavated from late eleventh-century contexts also had weapon injuries. Those from the middle to late eleventh century included three double graves from period 4b (Phase 110), and two double graves from period 4d (Phase 208). Within these double burials, skeletons number 1886 and 1873 displayed weapon wounds, as did 1902/1887, and 2351/2363; 1893 also had wounds though the inhumation with it, 1894, showed no traces of trauma, and a further pairing, 2371/2392, saw only the former with wounds.

As Daniell (2001: 222) has said: âWhen the similar archaeological phasing, the weapon injuries and five double burials with weapon injuries are all taken together, there is a strong likelihood of a single violent event. The most likely documented event was the Battle of Fulford Gate fought in 1066 shortly before the Battle of Stamford.' Fulford Gate was one of three major battles fought in England in that fateful year, resulting in a Viking victory over Saxon armies. It was, however, indecisive and the main Anglo-Saxon army under King Harold was able to crush the Viking forces at Stamford Bridge prior to marching south to face William of Normandy at the fateful Battle of Hastings.

Table 3.1.

The location of wounds to the skeletons in the double graves at Fishergate

| Skeleton number | Wound locations |

| 1886 | Spine (thoracic vertebrae 1, 2, 3, 6, 11 and lumbar vertebrae 2 and 3), scapula, humerus, lower arm/hand (possibly an old injury), femur (a pointed weapon injury, perhaps old) |

| 1873 | Spine (lumbar vertebrae 2 and 3), ribs, pelvis (pointed weapon injury), femur (pointed weapon injury) |

| 1893 | Skull (two wounds), mandible, ribs |

| 1902 | Ribs |

| 1887 | Skull (one wound), ribs |

| 2351 | Skull (two wounds) |

| 2363 | Humerus, pelvis |

| 2371 | Ribs |

Source

: after Daniell (2001).

At Riccall, North Yorkshire, only a few miles from Stamford Bridge, the second of the 1066 battles, a burial ground was uncovered in the 1950s. Several skeletons were found and others were unearthed during flood-bank construction work in the 1980s (see Environment Agency, 2005). On analysis, the bones of a number of the skeletons bore traces of combat injuries â of edged-weapon and projectile wounds. Were these the bodies of fleeing Vikings from the battle? Initially this was thought to be the case (Richards, 2001, postscript). However, several of the skulls from the excavations were examined by Dr Paul Budd (pers. comm.) of Durham University, whose Oxygen Isotope analysis of the teeth concluded that the bodies were probably indigenous Anglo-Saxons who had died in the tenth or eleventh centuries.

If the work at Fishergate tends to indicate that the bodies were of those killed in the Battle of Fulford Gate, excavations at another site seem even more unequivocally connected to Viking warfare in this period â perhaps against Anglo-Saxon opponents once more, though almost 200 years earlier. In the churchyard of St Wystan's, in Repton, Derbyshire, the disarticulated remains of some 249 individuals were found in a burial chamber by Martin Biddle and Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle. According to the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, the Viking âGreat Army' had its winter quarters here at Repton, at the site of the Anglo-Saxon monastery. Just to the north of the church of St Wystan's, and within the defensive ditch that the Vikings constructed, they buried numbers of their dead â perhaps a fitting place of repose as Repton was the chosen resting place for a number of the Mercian kings, including Ãthelbald (716â57) (Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle, 1992: 36). Among the burials, Number 511 was of particular interest, as the man had suffered weapon injuries and was, without doubt, a Viking.

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 5

Grave 511 was the burial of a man around 1.82m in height and at least 35â40, âwho had been killed by a massive cut into the head of the left femur. He lay with his hands together on the pelvis, and wore a necklace of two glass beads and a plain silver Thor's hammer with a ?bronze fastening. A copper-alloy buckle with traces of textile and leather from a ?belt lay at the waist. By the left leg was an iron sword of Petersen Type M in a wooden scabbard lined with fleece and covered with leather' (

ibid.

: 40â1). In addition to these grave goods, which illustrated the pagan Norse nature of the inhumed, two iron knives were discovered as was an iron key. Between the thighs of the man was a jackdaw bone and a wild boar's tusk.

Further fascinating elements of this burial came to light when it emerged that the grave itself had been covered by a series of broken stones, which included the smashed remnants of an Anglo-Saxon cross shaft (

ibid.

: 41). Additional analysis of the man's pathology was undertaken by Bob Stoddard, of Manchester University, who believed that, rather than having one simple wound to the skull, this individual had several elements of trauma. The man had been stabbed in the head (with two probable spear wounds to the skull), jaw, arm and thigh; each of his toes and both his heels were split lengthways; and marks to his spine suggested he had probably been disembowelled (Leonard, 2001). Stoddard believes that such mutilation had a particular end in mind: âThe mutilation was clearly done by someone who knew how to do it. It suggests the Saxons were in the habit of doing this when they caught Vikings ⦠Maybe they did it because they knew that Vikings believed they needed their bodies intact if they were going to go to Valhalla' (

ibid.

). It is also possible that the Viking's genitalia had been hacked off with an axe, resulting partly in the wound to the femur. This would perhaps explain the presence of the boar's tusk in this region of the skeleton; an attempt to make the man's body seem more complete.

If this scenario is close to the truth, one can imagine the rage of the man's comrades when his body was found and when they had to bury him. The smashing of the Christian cross, a symbol clearly connected to the beliefs of the people who had probably killed him, would have been an obvious act of retribution as the man was sent on his journey to the afterlife.

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 5

Grave 511, a Viking burial at Repton, Derbyshire

This is the body of a tall 35â40-year-old man, a Viking who worshipped the Norse gods as testified by his wearing of Thor's hammer. He was killed in a savage attack with multiple wounds, some of which seem to have been inflicted by spears. He was buried in preparation for entry to Valhalla and was given the broken remains of a Christian cross to cover his grave â the remnants of a conflicting belief set. Was the man killed in ambush, on the battlefield, or simply murdered? We do not know, but his body must have been in the hands of the perpetrators for some time for it to be mutilated before his friends had time to bury him.

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 6

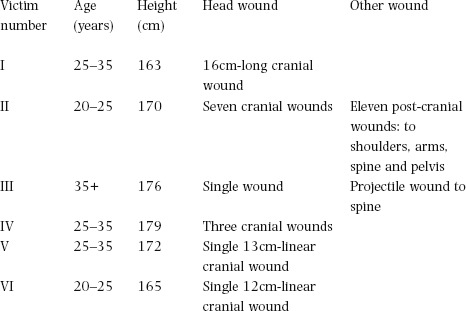

A cemetery of Anglo-Saxons has produced evidence for the wounds inflicted in Anglo-Saxon combat. At Eccles, Kent, six male skeletons on the site bore the scars of edged-weapon wounds, which would have proved fatal. All of these skeletons had one wound to the head, with two of them having more than one such wound. Of those with multiple wounds, the skeleton labelled by Wenham (1989: 123) as âVictim II', a male aged 20â25 years, had thirty bone injuries catalogued, with seven cranial and eleven post-cranial blows, blows to the back of the head, blows to the back of the trunk, and blows to the arms. âVictim III', a male aged over 35, had a single cranial injury, but also had a projectile wound to the third lumbar vertebra, with the iron projectile remaining in the spinal column. This arrowhead came to rest on the third lumbar vertebra. Manchester (1983a: 61) believes that its position indicated that the âarrow was shot at the upright victim, probably from fairly close range to his right. The injury did no more damage than create great pain, some bleeding and, in this instance at least, an insignificant opening in the spinal canal. This was insignificant because the victim was felled shortly afterwards by a tremendous blow to the right side of the back of the head'.

The linear wounds had fresh edges and showed no signs of healing. All had resulted in massive loss of blood and, in the case of Victim III, could have resulted in instantaneous death with the presumed sword blade having passed right through the brain. Wenham believed that all the blade wounds would have been caused by a sword (

seax

). Victims I, V, and VI had single injuries to the left side of the skull â classic patterning for a front-on attack by a right-handed adversary. Victims II, III and IV had multiple wounds as seen above â perhaps these were the result of more frenzied attacks. Victim II had wounds to the arms, which are indicative of unsuccessful self-defence (Wenham, 1989: 138). After being felled by blows to the back of the head, he suffered wounds to his back. Given that this was a cemetery site, it was impossible to tell through stratigraphy whether these burials were from a single engagement or whether they had been buried over a longer time period. Further to this assemblage it should be noted that a seventh skeleton, now lost, might have been female (

ibid.

: 123).

Table 3.2.

Wound summary of Eccles victims

Source

: Wenham (1989: 124â7).

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 6

Burial G, an Anglo-Saxon combat victim from Eccles in Kent

Victim number III from Eccles was a 176cm-tall man of over 35 years of age when he died. He had been hit from the side by an arrowhead, which had lodged in his spine causing great pain if not death or paralysis. The man was then dispatched by a blade that passed right through the back of his head, severing the brain.

FOUR

Chivalry's Price: Footsoldiers of the Middle Ages

O God of battles! Steel my soldiers' hearts.

(Shakespeare,

Henry V

,

IV

. i. 342)

For the purpose of this work, the period defined as âMedieval' covers the time from the Norman conquest of Britain in 1066 to the sixteenth century â a period in which the use of gunpowder became more widespread and the arrow, rather than the cannon's projectile, was the main missile weapon. Although drawing some comparative information from the crusades, we will concentrate on Britain and northern Europe.