The Trellis and the Vine (9 page)

Read The Trellis and the Vine Online

Authors: Tony Payne,Colin Marshall

Tags: #ministry training, #church

The point of using this sort of tool is not to turn Christian ministry into a set of lists but to help us

focus on people

—because ministry is about people, not programs. If we never think about people individually and work out where they are up to, and how and in what area they need to grow, how can we minister in anything other than a haphazard, scattergun way? It’s like a doctor thinking to himself, “Seeing each of my patients individually and diagnosing their illnesses is just too difficult and time consuming. Instead, I’m going to get all my patients to assemble together each week, and I’ll give them all the same medicine. I’ll vary the medicine a bit from week to week, and it will at least do everybody some good. And it’s much more efficient and manageable that way.”

Some readers may suspect that this is starting to sound rather too anti-church and anti-sermon, and when you see the title of chapter 8 (‘Why Sunday sermons are necessary but not sufficient’), your suspicions may get worse. We’ll talk more about the issues in that chapter; suffice to say at this point that we are very pro-church and we think that the ‘sermon’ is an essential, valuable and highly effective form of ministering God’s word—it’s just that it’s not the only form, nor the only way to see gospel growth happen. If growing the vine is about growing

people

, we need to help each person grow, starting from where they are at this very moment. There needs to be inefficient, individual people ministry, as well as the more efficient ministries that take place in larger groups. This is the sort of individualized ministry that Paul envisages in 1 Thessalonians 5:

We ask you, brothers, to respect those who labour among you and are over you in the Lord and admonish you, and to esteem them very highly in love because of their work. Be at peace among yourselves. And we urge you, brothers, admonish the idle, encourage the fainthearted, help the weak, be patient with them all. (1 Thess 5:12-14)

The leaders labour hard in their vital role, and are to be esteemed highly because of it. But there is an equally important role for the “brothers” to be involved in: ministering to all the various situations that individual Christians encounter in life.

This is another enormous benefit of using a diagnostic tool like the one above. It helps us see what people need next—which is always to help them move one step to the right. What Need-Help-Jean needs next is to gain (or regain) her solidity and stability in Christian faith. What Solid-Barry needs next is some encouragement and training to start ministering to others, rather than just growing in his own happy world. What Raising-Issues-Bob needs next is to get beyond discussing general issues of God or Christianity, and hear the gospel.

Incidentally, if you’re the pastor of a church, this tool also helps you to see where the gaps and holes and needs are. In a healthy ‘gospel growth’ church, there should be a decent spread of people across all categories. If you list out all the people you know, both in your congregation and the contacts on the fringe of the congregation, you’ll quickly see where the challenges are. If there are very few people in the outreach category, then your church is not doing enough to make contact with non-Christians and tell them the gospel. If there are lots in the outreach category but almost none in the follow-up category, there’s every chance that you’re running lots of events and programs to make contact with people, but not prayerfully sharing the gospel often enough so that people are actually converted and need to be followed up. And so on.

T

RAINING IS THE ENGINE

of gospel growth. Under God, the way to get more gospel growth happening is to train more and more mature, godly Christians to be vine-workers—that is, to see more people equipped, resourced and encouraged to speak the word prayerfully to other people, whether in outreach, follow-up or Christian growth.

Unfortunately, in most churches and for most pastors, hardly any effort goes into training. It’s basically seen as the pastor’s job to do the gospel growth, and since that is virtually impossible at a personal or individual level, it is all done at the general and large-group level. And before long, the management and running of events, groups, meetings and structures consumes the pastor’s time and the church member’s week.

There is another way. But before we talk more about what a training ministry looks like in practice, it’s time to pause and deal with some issues that have no doubt been brewing in some readers’ minds for some time.

[

1

] This diagnostic or planning table is shamelessly pinched and adapted from Peter Bolt’s excellent little book

Mission Minded

(Matthias Media, Sydney, 2000).

Chapter 8.

Why Sunday sermons are necessary but not sufficient

We’ve come to the point in the flow of our argument where we need to pause and consider in more detail how the model of training and growth we are proposing collides with the reality of our existing church structures and models and practices. Because collide it will. By far the greatest obstacle to rethinking and reforming our ministries is the inertia of tradition—whether the long-held traditions of our denominations and churchmanship, or the more recent traditions of the church growth movement that have become a kind of unspoken orthodoxy in many evangelical churches.

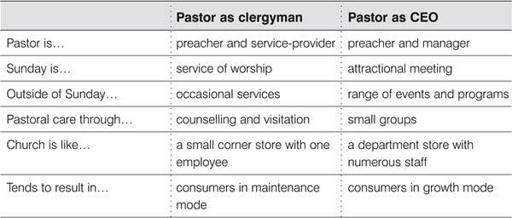

We will get to the somewhat alarming proposition contained in this chapter’s title in due course, but first let’s look at two very common approaches to pastoral ministry, and then contrast them with the approach of this book. Now of course these common approaches are stereotypes, and cannot reflect the multi-faceted reality of ministry in all its variety. All the same, we trust that you can recognize the structures and tendencies reflected in the descriptions, and make adjustments for your own situation accordingly.

There are three approaches or emphases we wish to examine, which we will call:

• the pastor as service-providing clergyman

• the pastor as CEO

• the pastor as trainer.

The pastor as service-providing clergyman

In this way of thinking about church life and ministry, the pastor’s role is to care for and feed the congregation. In this sense, he is a professional clergyman (whether or not he is called a ‘clergyman’), and there is an expectation on the part of both congregation and pastor that he is paid to fulfil certain core functions:

• to feed the flock through his Sunday sermons and administration of the sacraments

• to organize and run the Sunday gathering, which is seen as a time of worship for the congregation

• to put on various occasional services for different purposes, such as baptisms, weddings and possibly guest services

• to personally counsel congregation members, especially in times of crisis.

This is the classic Reformed-evangelical model of an ordained minister shepherding the flock given to him by Christ. And it has great strengths:

• It rightly puts regular preaching of the word at the centre of the ministry.

• It gathers the whole congregation as a family on Sunday for prayer, praise and preaching.

• The occasional services provide opportunities for outreach.

• The pastor cares for his people in times of crisis.

However, there are also very real (and obvious) disadvantages with this approach. For a start, the ministry that takes place in the congregation will be limited to the gifts and capacity of the pastor: how effectively he preaches, and how many people he can personally know and counsel. In this model, it becomes very difficult for the congregation to grow past a given ceiling (usually between 100 and 150 regular members).

Perhaps the most striking disadvantage of this way of thinking about ministry is that it feeds upon and encourages the culture of ‘consumerism’ that is already rife in our culture. It perfectly fits the spirit of our age whereby we pay trained professionals to do everything for us rather than do it ourselves—whether cleaning our car, ironing our shirts, or walking our dog. The tendency is for Christian life and fellowship to be reduced to an hour and a quarter on Sunday morning, with little or no relationship, and very little actual ministry taking place by the congregation themselves. In this sort of church culture, it becomes very easy for the congregation to think of church almost entirely in terms of ‘what I get out of it’, and thus to slip easily into criticism and complaint when things aren’t to their liking.

Even the good practice of pastoral counselling can become focused on ‘me’ being cared for by the pastor—such that if the assistant minister visits instead, this is not seen as adequate: “The pastor only sent him because he couldn’t be bothered coming himself”.

None of this is simply to blame the ‘consumer’! For all its historic strengths, the professional pastor-as-clergyman approach speaks loud and clear to church members that they are there to receive rather than to give. As a model, it tends to produce spiritual consumers rather than active disciples of Christ, and very easily gets stuck in maintenance mode. Outreach or evangelism, both for individual congregation members and the church as a whole, is down the list.

In many respects, this first way of thinking about pastoral ministry reflects the culture and norms of a different world—the world of 16th- and 17th-century Christianized nations, in which the whole community was in church, and in which the pastor was one of the few with sufficient education to teach.

The pastor as CEO

In many respects, the ‘church growth movement’ of the 1970s and 80s was a direct response to the traditional Reformed-evangelical view of ministry and church life. People saw some of the disadvantages that we’ve outlined and began to think about how they could be addressed. Speaking in very broad generalizations, the result was a number of key shifts:

• The pastor was still the professional clergyman, but his role became more focused on leading the congregation as an organization with particular goals; he was still a preacher and a pastoral service-provider, but he was also now a managerial leader responsible for making all these things happen on a larger scale. If there was going to be growth, then the pastor had to learn the difference between running a corner shop as a sole trader and managing a department store with numerous staff and a range of services.

• The focus of Sunday shifted towards an ‘attractional’ model, with the kind of music, decor and preaching that would be attractive to visitors and newcomers. If the church was to grow, its ‘shopfront’ needed to be much more appealing to the ‘target market’. It sounds tawdry when put like this, but for many churches it was profoundly gospel-centred. It stemmed from a godly desire to remove unnecessary cultural obstacles to the hearing of God’s word, and to make sure that the only thing weird, offensive or strange about church was the gospel itself.

• Instead of occasional services, the church growth movement spawned a revolution of programs and events, both for church members and for outsiders—everything from evangelistic courses and programs, to outreach events designed to be attractive to the non-Christian friends of the congregation, to seminars and programs to help congregation members with different aspects of their lives (how to raise children, how to deal with depression, and so on).

• In a church of 500 (rather than 150), how could individual members be known, cared for, prayed for and helped in times of crisis? Individual counselling by pastoral staff (let alone the senior pastor) was logistically impossible, especially given the range of other programs and activities happening. The answer was the rise of the small home group, in which members could have a set of personal relationships in which they could be known and cared for.

One of the key strengths and advantages of the church growth approach has been its promotion of congregational

involvement

. This is one of the key insights of the movement—that if you want someone to join your congregation and feel part of the place, they need to have something to do. Church growth research told us that if you found someone a role or job or opportunity for personal involvement in some ministry within the first six months of them being at your church, then your chances of retaining that person as a long-term member massively improved.

The other key strength of the ‘church growth’ approach is its recognition that if a congregation is to grow numerically, more work will need to be put into the trellis. As the cliché goes, the pastor will have to spend less time ‘in the business’ and more time ‘on the business’. This is simply an inevitable function of organizational growth and change, and ‘church growth’ thinking has helped many pastors to face these challenges of leadership.

There is no doubt that many churches have grown in the past 30 years through successfully applying ‘church growth’ principles. It has enabled churches to grow past 150, and to promote a more active involvement of congregation members in various church groups, activities and programs.

The downside has been that for all the growth in numbers and involvement, many ‘church growth’ churches have also accepted the consumerist assumptions of our society. Success has been achieved by providing a more attractive and broadly appealing ‘product’, but the result is not always more prayerful ministry of the word, and thus more real spiritual growth. Lots of people are involved and cared for and receiving help in their lives, but are people growing as disciples and in mission?

Willow Creek Community Church recently discovered this after 20 years at the forefront of the church growth movement. In a detailed survey of their members, the Willow Creek staff discovered that despite running one of the slickest and most well-organized churches in America—with superb structures, high-quality music and drama, and an impressive level of involvement of members in all manner of small groups and activities—personal spiritual growth as disciples was not happening.

[1]

We could represent these two approaches in a table like this:

The pastor as trainer

We have been arguing from the Bible that:

• genuine spiritual growth only comes as the Holy Spirit applies the word of God to people’s hearts

• all Christians have the privilege and responsibility to prayerfully speak the word of God to each other and to non-Christians, as the means by which God gives this growth.

If these two foundational propositions are true, then we need a different mental picture of church life and pastoral ministry—one in which the prayerful speaking of the word is central,

and

in which Christians are trained and equipped to minister God’s word to others. Our congregations become centres of training where people are trained and taught to be disciples of Christ who, in turn, seek to make other disciples.

• In this way of thinking, the pastor is a prayerful preacher who shapes and drives the entire ministry through his biblical, expositional preaching. This is essential and foundational. But crucially, the pastor is also a trainer. His job is not just to provide spiritual services, nor is it his job to do all of the ministry. His task is to teach and train his congregation, by his word and his life, to become disciple-making disciples of Jesus. There is a radical dissolution, in this model, of the clergy-lay distinction. It is not minister and ministered-to, but the pastor and his people working in close partnership in all manner of word ministries.

• Adding this training emphasis greatly enhances what we do in our Sunday gatherings, because it builds and grows the gospel maturity of those who attend. We are training people to be contributors and servants, not spectators and consumers. The congregation becomes a gathering of disciple-making disciples in the presence of their Lord—meeting with him, listening to his word, responding to him in repentance and worship and faith, and discipling one another. The congregational gathering becomes not only a theatre for ministry (where the word is prayerfully spoken) but also a spur and impetus for the worship and ministry that each disciple will undertake in the week to come.

• Where the pastor is a trainer, there will be a focus on people ministering to people, rather than on structures, programs and events. Evangelism will take place as disciples reach out to the people around them: in their homes, their extended families, their streets, their workplaces, their schools, and so on. Events and programs and guest services will still be useful structures to focus people’s efforts and provide opportunities to invite friends, but the real work of prayerful evangelism will take place as the disciples do it themselves. Taking our example from the previous chapter, it will happen as Don takes the time to get to know Bob, and then offers to read through one of the Gospels with him.

• Pastoral care, in this approach, is also founded on disciples being trained to care for and disciple other Christians. Small groups may be utilized as one convenient structure in which this may happen, but the structure itself will not make it happen. Our goal should not simply be to ‘get people into small groups’. Unless Christians are taught and trained to meet with each other, to read the Bible and pray with each other, and to urge and spur one another on to love and good works, the small-group structure will not be effective for spiritual growth. People may get to know each other in small groups, feel a sense of togetherness and community, develop warm friendships, and be more bound in to regular attendance and involvement in the church as a result—but none of these things amounts to growth in the gospel. It’s very possible for a great deal of the personal encouragement and discipling work in a congregation to be done one to one, without any involvement in structured small groups.

[2]