The Trellis and the Vine (10 page)

Read The Trellis and the Vine Online

Authors: Tony Payne,Colin Marshall

Tags: #ministry training, #church

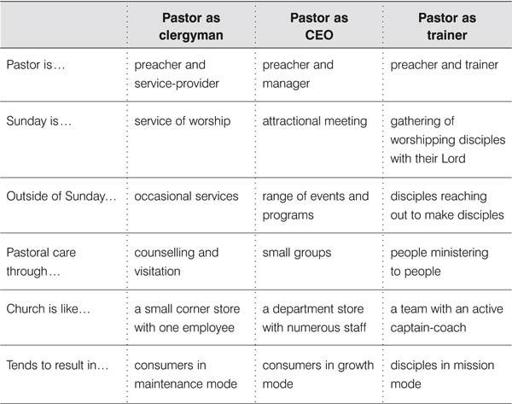

The ‘pastor-as-trainer’ approach contrasts with our other two models like this:

At this point, it is worth repeating the caveats made earlier in this chapter (in case they have faded from memory). We are unavoidably dealing with straw men and stereotypes in this discussion. No particular church will be a perfect example of any one of these approaches or emphases; there will be massive individual variation. Indeed, you may look at your own congregation and recognize it as a strange amalgam of two or more!

All the same, as a thought experiment, delineating these three approaches is helpful. The tendencies and traditions are recognizable, as are the consequences.

The insufficient sermon

Perhaps the best way to sharpen what we are arguing for in this chapter is to say that Sunday sermons are necessary but not sufficient. This may sound like heresy to some of our readers, and in one sense we hope it does sound a bit shocking. Are we de-valuing preaching? Surely godly, faithful expository sermons accompanied by prayer are all that is really required for the building of Christ’s church?

Sermons are needed, yes, but they are not

all

that is needed. Let’s be absolutely clear: the preaching of powerful, faithful, compelling biblical expositions is absolutely vital and necessary to the life and growth of our congregations. Weak and inadequate preaching weakens our churches. As the saying goes, ‘sermonettes produce Christianettes’. Conversely, clear, strong, powerful public preaching is the bedrock and foundation upon which all other ministry in the congregation is built. The sermon is a rallying call. It is where the whole congregation can together feed on God’s word and be challenged, comforted and edified. The public preaching ministry is like a framework that sets the standard and agenda for all the other word ministries that take place. We do not want to see less emphasis on preaching or less effort go into preaching! On the contrary, we long for more godly, gifted Bible teachers who will set congregations on fire with the power of the preached word.

To say that sermons (in the sense of Bible expositions in our Sunday gatherings) are necessary but not sufficient is simply to stand on the theological truth that it is the word of the gospel that is sufficient, rather than any one particular form of its delivery. We might say that the speaking of the word of the gospel under the power of the Spirit is entirely sufficient—it’s just that on its own, the 25-minute sermonic form of it is not.

We say this because the New Testament compels us to. As we have already seen, God expects all Christians to be disciple-makers by prayerfully speaking the word of God to others—in whatever way and to whatever extent that their gifting and circumstances allow. When God has gifted all the members of the congregation to help grow disciples, why should we silence the contribution of all but one of them (the pastor), and think that this is sufficient or acceptable?

In his fine book on preaching,

Speaking God’s Words

, Peter Adam conducts a detailed survey of the ministries of the word in the New Testament, together with a consideration of the ministry practices of John Calvin, Richard Baxter and ministries in our churches today. He concludes that:

…while preaching… is one form of the ministry of the Word, many other forms are reflected in the Bible and in contemporary Christian church life. It is important to grasp this point clearly, or we shall try and make preaching carry a load which it cannot bear; that is, the burden of doing all that the Bible expects of every form of ministry of the Word.

[3]

Adam goes on to define preaching as the “the explanation and application of the Word to the congregation of Christ in order to produce corporate preparation for service, unity of faith, maturity, growth and upbuilding”.

[4]

But he points out that Sunday preaching is not the only way to address the edification of the body:

While individuals may be edified in so far as they are members of the congregation, there may well be other areas in which they need correction and training in righteousness which they will not obtain through the Sunday sermon, because by its very nature it is generalist in its application.

[5]

Well, you may ask, what is being suggested—that as well as a 25-minute sermon, we have 50 one-minute testimonies from the congregation?

That might make for a fascinating and encouraging (if rather long) Sunday morning, but that is not what we’re proposing. Because Sunday is not the only place where the action is. This is something that one of the great gospel ministers of our Reformed-evangelical heritage knew very well.

The example of Richard Baxter

The name of Richard Baxter will forever be associated with his classic work

The Reformed Pastor

. Interestingly, by ‘Reformed’, Baxter did not mean a particular brand of doctrine (although his own somewhat idiosyncratic theology was certainly ‘Reformed’ in that sense), but rather a ministry that was renewed and renovated, and that abounded in vigour, zeal and purpose. “If God would but reform the ministry,” Baxter wrote, “and set them on their duties zealously and faithfully, the people would certainly be reformed”.

[6]

Baxter’s remarkable ministry among the 800 families of the village of Kidderminster began in 1647, and transformed the parish. His strategy of pastoral ministry was formed during the chaotic vacuum of ecclesiastical authority and discipline following the English Civil War and the failure of the Westminster reforms. Baxter wanted to ensure that every parishioner understood the basic tenets of the faith and the godly life, and

The Reformed Pastor

, published in 1656, consists of an extended exhortation to his fellow ministers to conduct a ministry that is not merely formal, but personal and local.

In calling for this reformation of ministry and church life, Baxter’s chief motive was the salvation of souls: “We are seeking to uphold the world, to save it from the curse of God, to perfect the creation, to attain the ends of Christ’s death, to save ourselves and others from damnation, to overcome the devil, and demolish his kingdom, to set up the kingdom of Christ, and to attain and help others to the kingdom of glory”.

[7]

This overriding and confronting challenge to the conversion of souls permeates each section of

The Reformed Pastor

—whether speaking about the pastor’s oversight of himself or his oversight of the flock. This, Baxter had come to believe, was the true cause and agenda for reformation of the church. It could not be achieved merely through structural changes:

I can well remember the time when I was earnest for the reformation of matters of ceremony… Alas! Can we think that the reformation is wrought, when we cast out a few ceremonies, and changed some vestures, and gestures, and forms! Oh no, sirs! It is the converting and saving of souls that is our business. That is the chiefest part of reformation, that doth most good, and tendeth most to the salvation of the people.

[8]

In Baxter’s view, if the ministry was going to be reformed to focus on the conversion of souls, pastors had to devote extensive time to “the duty of personal catechizing and instructing the flock”. He saw personal work with people as having irreplaceable value, because it provided “the best opportunity to impress the truth upon their hearts, when we can speak to each individual’s particular necessity, and say to the sinner, ‘Thou art the man’”.

[9]

Public preaching was not enough, according to Baxter. In fact, he went so far as to say “I have no doubt that the Popish auricular confession is a sinful novelty… but our common neglect of personal instruction is much worse”!

[10]

It was only through personal catechizing that Baxter could find those who:

…have been my hearers eight or ten years, who know not whether Christ be God or man, and wonder when I tell them the history of his birth and life and death as if they have never heard it before… I have found that some ignorant persons, who have been so long unprofitable hearers, have got more knowledge and remorse in half an hour’s close discourse, than they did from ten years public preaching. I know that preaching the gospel publicly is the most excellent means, because we speak to many at once. But it is usually far more effectual to preach it privately to a particular sinner.

[11]

Elsewhere, Baxter wrote:

It is but the least part of the Minister’s work, which is done in the Pulpit… To go daily from one house to another, and see how you live, and examine how you profit, and direct you in the duties of your families, and in your preparation for death, is the great work.

[12]

Baxter worked hard to convince others of the need for this kind of ministry reformation. He formed the ‘Worcester Association’ to promote the cause, members of which embraced the commitment to know personally each person in their charge—a challenging commitment even now, but revolutionary in Baxter’s time.

Sadly, however, Baxter’s example was “widely hailed, less widely followed, and finally, perhaps more often than not, simply abandoned…”

[13]

Certainly, not many pastors today walk in his footsteps, even though they may have read

The Reformed Pastor

at some point in seminary and nodded approvingly. The

idea

of personal ministry alongside preaching ministry is admirable and hard to disagree with. It is also thoroughly biblical. Paul says to the Ephesian elders that he “did not shrink from declaring to you anything that was profitable, and teaching you in public and from house to house” (Acts 20:20). The location for word ministry is necessarily public, but it is also inescapably personal and domestic. According to Baxter, this is the only way we can fulfil Paul’s powerful exhortation to those same elders: “Pay careful attention to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God, which he obtained with his own blood” (Acts 20:28).

Given that our context is undeniably very different from Baxter’s—culturally, politically, socially, educationally—how do his insights inform our understanding of ministry? There are four key challenges:

• Evangelism is at the heart of pastoral ministry. Ministry is not about just dealing with immediate crises or problems, or about building numbers, or about reforming structures. It is fundamentally about preparing souls for death.

• Ministers need not be tied to traditional structures but should use whatever ‘means’ (Baxter’s term) available to call people to repentance and salvation. For Baxter, this meant not being tied to the pulpit, but also going into people’s houses to instruct and exhort them.

• We should focus not only on what we are teaching, but also on what the people are learning and applying.

• In many respects, in our era of widespread education, there is even more scope to implement Baxter’s vision of personal catechizing. In many parts of the world, there is now a highly-educated laity who can not only learn well, but also very ably teach others. The personal house-to-house discipling can be done not only by the pastor, but also by the disciple-makers that the pastor trains.

One of the first steps in applying these challenges is to conduct an honest audit of all your congregational programs, activities and structures, and assess them against the criteria of gospel growth. How many of them are still useful vehicles for outreach, follow-up, growth or training? Is there duplication? Are some structures or regular activities long past their use-by date? Saying ‘yes’ to more personal ministry almost always means saying ‘no’ to something else.

However, even freeing up some time in the diary may still leave us feeling swamped with the amount of ‘people work’ there is to do. That’s why we need co-workers.

[

1

] See G Hawkins and C Parkinson,

Reveal: Where Are You?

, Willow Creek Resources, Chicago, 2007.

[

2

] For further thinking about small groups and how they can be positive vehicles for gospel growth, see Colin Marshall,

Growth Groups

, Matthias Media, Sydney, 1995.

[

3

] Peter Adam,

Speaking God’s Words: A Practical Theology of Preaching

, IVP, Leicester, 1996, p. 59.

[

4

] Adam, p. 71.

[

5

] Adam, p. 71.