The Trellis and the Vine (15 page)

Read The Trellis and the Vine Online

Authors: Tony Payne,Colin Marshall

Tags: #ministry training, #church

Chapter 11.

Ministry apprenticeship

What happens between someone showing the potential to be set apart for particular responsibilities in gospel work, and them arriving at that point (as a missionary for example, or an evangelist, or a pastor in a congregation)? The normal answer is ‘seminary’ or ‘theological college’. However, a growing number of churches and ministry candidates are making use of an intermediate step—a ministry traineeship or apprenticeship, which comes before formal theological education, and tests and trains and develops people along the path to full-time ministry.

An organization close to both of the authors’ hearts—the Ministry Training Strategy (MTS)—has spent the past 20 years helping churches set up two-year ministry apprenticeships of this kind in churches throughout Australia, with offshoots in Canada, Britain, France, the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Singapore, New Zealand, Taiwan, Japan, Chile and South Africa. The basic idea is that ‘people worth watching’ are recruited into a two-year, full-immersion experience of working for a church or other Christian ministry. Their convictions, character and competencies are tested and developed. Under the supervision of an experienced minister, they ‘catch’ the nature and rhythms of Christian ministry, picking up valuable lessons and skills, and testing their suitability for long-term gospel work.

The MTS apprenticeship began in 1979 when Phillip Jensen started training a few keen, able university graduates who had a heart for God. At the time, there was no long-term vision or plan for expansion. But since 1979, over 1200 MTS apprentices have been trained in churches and campus ministries throughout Australia. Of these, over 200 are currently engaged in theological study in various colleges, and another 400 plus men and women have completed their formal studies and are now serving as full-time ministry workers worldwide.

[1]

One of the most frequent questions we have been asked over the years is:

Why bother with an apprenticeship?

Given that we send our apprentices on to formal theological study, does the apprenticeship really add anything significant? It’s a big sacrifice for ministry candidates to spend an extra two years training, and it’s a big ask for pastors and churches to provide mentoring and remuneration for apprentices who are often raw and untested. What benefits have we seen for those who do a ministry apprenticeship? Here are a few reflections.

1. Apprentices learn to integrate word, life and ministry practice

In the classroom, imparting and processing information is the focus, and it is not always immediately obvious how the word shapes all of life and ministry. There is an inevitable and quite appropriate level of abstraction. However, in a ministry apprenticeship, the trainer and the apprentice study the Scriptures together week by week, and wrestle with their application to pastoral issues, theological fashions and ministry plans. The apprentice learns to think biblically and theologically about everything, and works this out practically with his trainer.

2. Apprentices are tested in character

A pastor working closely with an apprentice can see what might not be seen in the classroom context. The gap between image and reality is exposed in the pressures and hassles of ministry life. The real person is revealed—the true motivations, the capacity for love and forgiveness, the scars and pain from the past, and so on. A wise trainer can build the godly character of the young minister through the word, prayer, accountability and modelling.

3. Apprentices learn that ministry is about people, not programs

We know that ministry is about the transformation of people and the building of godly communities through the gospel. More than anything else, an apprenticeship is two years of working with people—meeting with unbelievers, discipling young Christians, training youth leaders, leading small groups or comforting those who are struggling. Our goal is that apprentices spend 20 hours of their week in face-to-face ministry with people, Bible open. They learn firsthand that ministry is about people, not structures.

4. Apprentices are well-prepared for formal theological study

During the two years of ministry involvement, many biblical and theological issues are raised and discussed in the proper context of evangelism and church-building. By the end, apprentices are eager for the opportunity to pursue these questions rigorously in further study. The motivation and context for further study becomes life and ministry preparation, rather than passing exams.

5. Apprentices learn ministry in the real world

One of the problems with the classroom is that the student does not need to own the ideas in the same way as he would in the pulpit or in one-to-one pastoral ministry. His learning is abstracted from everyday life and ministry. He learns about ten different views of the atonement in order to pass his exams, and not because anything hangs on the differences between them. Teaching the truth to others helps the apprentice understand the importance of theological training.

Another problem with a purely academic training model is that it suits certain personalities (i.e. those disposed to reading, thinking, analyzing and writing). However, some of our best evangelists and church-planters might be people who struggle in the classroom. These people thrive in a context where they are talking and preaching and building ministries while being tutored along the way. In academia they would be deemed failures.

6. Apprentices learn to be trainers of others so that ministry is multiplied

Because apprentices have had the experience of being personally mentored in life and ministry, they imbibe what we call ‘the training mindset’. When they are leading a ministry in the future, they instinctively equip co-workers and build ministry teams. Those who only learn ministry in the classroom often do not catch the vision of entrusting the ministry to others. Those who were trained as apprentices tend to look for their own apprentices when they are leading a church.

7. Apprentices learn evangelism and entrepreneurial ministry

Apprenticeships provide an opportunity to think strategically and creatively about ministry. In our post-Christian, pluralistic, multicultural missionary context, many pastors no longer have a flock sitting in the pews waiting for the Sunday sermon. Apprentices can experiment with new ways of reaching people and taking the initiative to start new groups and programs.

I

N MANY WAYS

MTS is an application of Paul’s words to Timothy: “…what you have heard from me in the presence of many witnesses entrust to faithful men who will be able to teach others also” (2 Tim 2:2). As Paul draws near to the end, he knows that the continued faithful proclamation of the gospel will not be secured by the writing of doctrinal confessions, or by the creation of institutional structures (as important as these are in their own way). The gospel will only be guarded and spread as it is passed from one faithful hand to the next, as each generation of faithful preachers pass their sacred trust on to the next generation, who in turn teach and train others.

MTS is really about passing on the gospel baton to the next generation of runners. The MTS handbook of ministry apprenticeship—called

Passing the Baton

—has lots of information about what two-year apprenticeships can achieve, how to set them up and run them, how to recruit and train apprentices, and so on. We won’t repeat the information here.

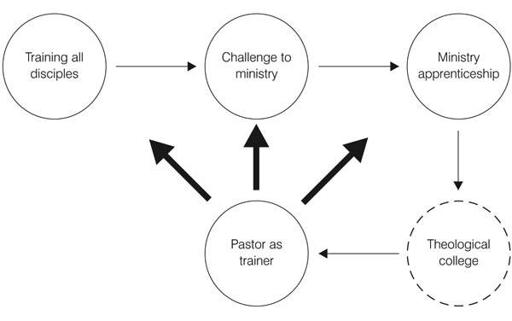

However, it’s worth thinking further about where we’ve come to in the cycle of training and growth. We began, you may recall, by saying that all Christians should be trained to be disciple-making disciples—trained in their knowledge of God (convictions), their godliness (character) and their ability to serve and minister to others (competencies). We suggested that the way to begin was to choose just a small number of potential co-workers and start to train them, in the expectation that some of these co-workers would in turn be able to train others. As this cycle of training continues, a workforce of disciple-makers starts to form—people who labour alongside you to help other people make progress in ‘gospel growth’.

As you keep discipling and training, you begin to notice certain people with real potential for ministry—people worth watching. These are the people you challenge and recruit as the next generation of ‘recognized gospel workers’. They embark on a ministry apprenticeship, and then go to Bible or theological college, after which they head off into ministry to begin training disciples… and the cycle starts again.

At least, that’s how the theory goes. In reality, of course, it tends to be messier and less easy to chart. Some ministry apprentices don’t go on to theological college—their two-year stint helps them realize (or helps their trainers realize) that they don’t have either the character or the competencies for recognized gospel work. For those who do go through theological college, an enormous variety of ministry opportunities awaits them on the other side—from becoming a missionary overseas, to pastoring a congregation, to returning to secular work and being a volunteer co-worker in a new church-plant.

It also gets messy because sometimes we recruit the wrong people. There are a number of common mistakes:

• We only recruit people like ourselves—people who fit with our own particular personality or style of ministry.

• We overlook the maverick or the revolutionary, who is harder to train but might evangelize nations.

• We miss the creative or intuitive person, who is poor administratively but will reach people in ways we haven’t thought of.

• We recruit the flashy, outgoing young superstar rather than the person of real character and substance.

• We recruit only for one kind of ministry—usually the traditional form of it in our denomination—rather than starting with a gifted, godly person and thinking about what kind of ministry might be built around them.

• We don’t let people escape from the box into which we’ve put them; we don’t let them outgrow the first impressions we have of them.

• We wait too long to recruit someone, and they make family or career decisions that close off ministry options.

Whoever you recruit, one hard truth must be faced: recruiting people for ministry, training them as apprentices, and sending them off to Bible college will result in a steady departure of your best and most gifted church members. This is a challenge to your gospel heart. What are you more interested in: the growth of your particular congregation, or the growth of the kingdom of God? Are you committed to church growth or to gospel growth? Do you want more numbers in the pew now, or more labourers for the harvest over the next 50 years?

It’s easy to give the right answer in theory. But faith without works is dead. We demonstrate our trust in the power of the gospel, and in the worldwide kingdom of Christ, when we keep pushing our best and brightest young people out the door and off into gospel work.

The marvellous thing about generosity is that God loves it, and blesses it. In our experience, those churches that don’t try to hold on to their people, but continually train them and generously export them off into further training and ministry elsewhere, are the churches that God showers with more and more new people to train.

The training mentality is an engine of growth and dynamism. It multiplies ministry because it multiplies ministers. It continually generates and develops disciple-making disciples—both within our congregations and abroad in the world—to the glory of the Lord Jesus, whose authority extends over all, even to the end of the age.

[

1

] See appendix 3 for a fascinating interview between Col Marshall and Phillip Jensen about MTS training.