The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet: A Novel (2 page)

Read The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet: A Novel Online

Authors: David Mitchell

Tags: #07 Historical Fiction

Orito asks the maid, 'When did the waters break?'

The maid is still mute with astonishment at hearing a foreign language.

'Yesterday morning, during the Hour of the Dragon,' says the stony-voiced housekeeper. 'Our lady entered labour soon after.'

'And when was the last time that the baby kicked?'

'The last kick would have been around noon today.'

'Dr Maeno, would you agree the infant is in' - she uses the Dutch term - 'the "transverse breech position"?'

'Maybe,' the doctor answers in their code-tongue, 'but without an examination . . .'

'The baby is twenty days late, or more. It should have been turned.'

'Baby's resting,' the maid assures her mistress. 'Isn't that so, Dr Maeno?'

'What you say . . .' the honest doctor wavers '. . . may well be true.'

'My father told me,' Orito says, 'Dr Uragami was overseeing the birth.'

'So he was,' grunts Maeno, 'from the comfort of his consulting rooms. After the baby stopped kicking Uragami ascertained that, for geomantic reasons discernible to men of his genius, the child's spirit is reluctant to be born. The birth henceforth depends on the mother's will-power.'

The rogue

, Maeno needs not add,

dares not bruise his reputation by presiding over the still-birth of such an estimable man's child

. 'Chamberlain Tomine then persuaded the Magistrate to summon me. When I saw the arm, I recalled your doctor of Scotland, and requested your help.'

'My father and I are both deeply honoured by your trust,' says Orito . . .

. . . and I curse Uragami

, she thinks,

for his lethal unwillingness to lose face

.

Abruptly, the frogs stop croaking and, as though a curtain of noise falls away, the sound of Nagasaki can be heard, celebrating the safe arrival of the Dutch ship.

'If the child is dead,' says Maeno in Dutch, 'we must remove it now.'

'I agree.' Orito asks the housekeeper for warm water and strips of linen, and uncorks a bottle of Leiden salts under the concubine's nose to win her a few moments' lucidity. 'Miss Kawasemi, we are going to deliver your child in the next few minutes. First, may I feel inside you?'

The concubine is seized by the next contraction, and loses her ability to answer.

Warm water is delivered in two copper pans as the agony subsides. 'We should confess,' Dr Maeno proposes to Orito in Dutch, 'the baby is dead. Then amputate the arm to deliver the body.'

'First, I wish to insert my hand to learn whether the body is in a convex lie or concave lie.'

'If you can discover this without cutting the arm' - Maeno means 'amputate' - 'do so.'

Orito lubricates her right hand with rape-seed oil and addresses the maid: 'Fold one linen strip into a thick pad . . . yes, like so. Be ready to wedge it between your mistress's teeth, otherwise she might bite off her tongue. Leave spaces at the sides, so she can breathe. Dr Maeno, my inspection is beginning.'

'You are my eyes and ears, Miss Aibagawa,' says the doctor.

Orito works her fingers between the foetus's biceps and its mother's ruptured labia until half her wrist is inside Kawasemi's vagina. The concubine shivers and groans. 'Sorry,' says Orito, 'sorry . . .' Her fingers slide between warm membranes and skin and muscle still wet with amniotic fluid and the midwife pictures an engraving from that enlightened and barbaric realm, Europe . . .

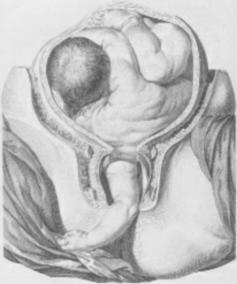

If the transverse lie is convex, recalls Orito, where the foetus's spine is arched backwards so acutely that its head appears between its shins like a Chinese acrobat, she must amputate the foetus's arm, dismember its corpse with toothed forceps, and extract it, piece by grisly piece. Dr Smellie warns that any remnant left in the womb will fester and may kill the mother. If the transverse lie is concave, however, Orito has read, where the foetus's knees are pressed against its chest, she may saw off the arm, rotate the foetus, insert crotchets into the eye-sockets, and extract the whole body, head first. The midwife's index finger locates the child's knobbly spine, traces its midriff between its lowest rib and its pelvic bone, and encounters a minute ear; a nostril; a mouth; the umbilical cord; and a prawn-sized penis. 'Breech is concave,' Orito reports to Dr Maeno, 'but cord is around neck.'

'Do you think the cord can be released?' Maeno forgets to speak Dutch.

'Well, I must try. Insert the cloth,' Orito tells the maid, 'now, please.'

When the linen wad is secured between Kawasemi's teeth, Orito pushes her hand in deeper, hooks her thumb around the embryo's cord, sinks four fingers into the underside of the foetus's jaw, pushes back his head, and slides the cord over his face, forehead and crown. Kawasemi screams, hot urine trickles down Orito's forearm, but the procedure worked first time: the noose is released. She withdraws her hand and reports, 'The cord is freed. Might the doctor have his -' there is no Japanese word '- forceps?'

'I brought them along,' Maeno taps his medical box, 'in case.'

'We might try to deliver the child' - she switches to Dutch - 'without amputating the arm. Less blood is always better. But I need your help.'

Dr Maeno addresses the chamberlain: 'To help save Miss Kawasemi's life, I

must

disregard the Magistrate's orders and join the midwife inside the curtain.'

Chamberlain Tomine is caught in a dangerous quandary.

'You may blame me,' Maeno suggests, 'for disobeying the Magistrate.'

'The choice is mine,' decides the chamberlain. 'Do what you must, Doctor.'

The spry old man crawls under the muslin, holding his curved tongs.

When the maid sees the foreign contraption, she exclaims in alarm.

' "Forceps",' the doctor replies, with no further explanation.

The housekeeper lifts the muslin to see. 'No, I don't like the look of

that

! Foreigners may chop, slice and call it "medicine", but it is quite unthinkable that--'

'Do

I

advise the housekeeper,' growls Maeno, 'on where to buy fish?'

'Forceps,' explains Orito, 'don't cut - they turn and pull, just like a midwife's fingers but with a stronger grip . . .' She uses her Leiden salts again. 'Miss Kawasemi, I'm going to use this instrument,' she holds up the forceps, 'to deliver your baby. Don't be afraid, and don't resist. Europeans use them routinely - even for princesses and queens. We'll pull your baby out, gently and firmly.'

'Do so . . .' Kawasemi's voice is a smothered rattle. 'Do so . . .'

'Thank you, and when I ask Miss Kawasemi to

push

. . .'

'Push . . .' She is fatigued almost beyond caring. 'Push. . .'

'How many times,' Tomine peers in, 'have you used that implement?'

Orito notices the chamberlain's crushed nose for the first time: it is as severe a disfigurement as her own burn. 'Often, and no patient ever suffered.' Only Maeno and his pupil know that these 'patients' were hollowed-out melons whose babies were oiled gourds. For the final time, if all goes well, she works her hand inside Kawasemi's womb. Her fingers find the foetus's throat; rotate his head towards the cervix, slip, gain a surer purchase and swivel the awkward corpse through a third turn. 'Now, please, Doctor.'

Maeno slides in the forceps around the protruding arm up to the fulcrum.

The onlookers gasp; a parched shriek is wrenched from Kawasemi.

Orito feels the forceps' curved blades in her palm: she manoeuvres them around the foetus's soft skull. 'Close them.'

Gently but firmly the doctor squeezes the forceps shut.

Orito takes the forceps' handles in her left hand: the resistance is spongy but firm, like

konnyaku

jelly. Her right hand, still inside the uterus, cups the foetus's skull.

Dr Maeno's bony fingers encase Orito's wrist.

'What is it you're waiting for?' asks the housekeeper.

'The next contraction,' says the doctor, 'which is due any--'

Kawasemi's breathing starts to swell with fresh pain.

'One and two,' counts Orito, 'and -

push

, Kawasemi-

san

!'

'Push, Mistress!' exhort the maid and the housekeeper.

Dr Maeno pulls at the forceps; with her right hand, Orito pushes the foetus's head towards the birth canal. She tells the maid to grasp the baby's arm and pull. Orito feels the resistance grow as the head reaches the birth canal. 'One and two . . .

now

!' Squeezing the glans of the clitoris flat comes a tiny corpse's matted crown.

'Here he is!' gasps the maid, through Kawasemi's animal shrieks.

Here comes the baby's scalp; here his face, marbled with mucus . . .

. . . Here comes the rest of his slithery, clammy, lifeless body.

'Oh, but - oh,' says the maid. 'Oh. Oh.

Oh

. . .'

Kawasemi's high-pitched sobs subside to moans, and deaden.

She knows

. Orito discards the forceps, lifts the lifeless baby by his ankles and slaps him. She has no hope of coaxing out a miracle: she acts from discipline and training. After ten hard slaps she stops. He has no pulse. She feels no breath on her cheek from the lips and nostrils. There is no need to announce the obvious. Splicing the cord near the navel, she cuts the gristly string with her knife, bathes the lifeless boy in a copper of water and places him in the crib.

A crib for a coffin

, she thinks,

and a swaddling sheet for a shroud

.

Chamberlain Tomine gives instructions to a servant outside. 'Inform His Honour that a son was still-born. Dr Maeno and his midwife did their best, but were powerless to alter what Fate had decreed.'

Orito's concern is now puerperal fever. The placenta must be extracted;

yakumoso

applied to the perineum; and blood staunched from an anal fissure.

Dr Maeno withdraws from the curtained tent to give the midwife space.

A moth the size of a bird enters, and blunders into Orito's face.

Batting it away, she knocks the forceps off one of the copper pans.

The forceps clatter on to a pan lid; the loud clang frightens a small creature that has somehow found its way into the room; it mewls and whimpers.

A puppy?

wonders Orito, baffled.

Or a kitten?

The mysterious animal cries again, very near: under the futon?

'Shoo that thing away!' the housekeeper tells the maid. 'Shoo it!'

The creature mewls again; and Orito realises it is coming from the crib.

Surely not

, thinks the midwife, refusing to hope.

Surely not . . .