The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy (104 page)

Read The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy Online

Authors: Irvin D. Yalom,Molyn Leszcz

Tags: #Psychology, #General, #Psychotherapy, #Group

Results: What Did We Find?

First, the participants rated the groups very highly. At the termination of the group, the 170 subjects who completed the groups considered them “pleasant” (65 percent), “constructive” (78 percent), and “a good learning experience” (61 percent). Over 90 percent felt that encounter groups should be a regular part of the elective college curriculum. Six months later, the enthusiasm had waned, but the overall evaluation was still positive.

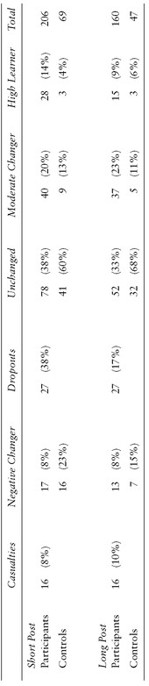

So much for testimony. What of the overall, more objective battery of assessment measures? Each participant’s outcome (judged from all assessment measures) was rated and placed in one of six categories: high learner, moderate changer, unchanged, negative changer, casualty (significant, enduring, psychological decompensation that was due to being in the group), and dropout. The results for all 206 experimental subjects and for the sixty-nine control subjects are summarized in

Table 16.1

. (“Short post” is at termination of group and “long post” is at six-month follow-up.)

TABLE 16.1

Index of Change for All Participant Who Began Strudy

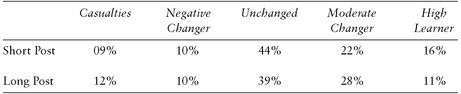

TABLE 16.2

Index of Change for Those Who Completed Group (N = 179 Short Post, 133 Long Post)

SOURCE: Morton A. Lieberman, Irvin D. Yalom, and Matthew B. Miles,

Encounter Groups: First Facts

(New York: Basic Books, 1973).

Table 16.1

indicates that approximately one-third of the participants at the termination of the group and at six-month follow-up had undergone moderate or considerable positive change. The control population showed much less change, either negative or positive.

The encounter group thus clearly influenced change, but for both better and worse.

Maintenance of change was high: of those who changed positively, 75 percent maintained their change for at least six months.

To put it in a critical fashion, one might say that

Table 16.1

indicates that, of all subjects who began a thirty-hour encounter group led by an acknowledged expert, approximately two-thirds found it an unrewarding experience (either dropout, casualty, negative change, or unchanged).

Viewing the results more generously, one might put it this way. The group experience was a college course. No one expects that students who drop out will profit. Let us therefore eliminate the dropouts from the data (see

table 16.2

). With the dropouts eliminated, it appears that

39 percent of all students taking a three-month college course underwent some significant positive personal change that persisted for at least six months.

Not bad for a twelve-week, thirty-hour course! (And of course this perspective on the results has significance in the contemporary setting of group therapy, where managed care has mandated briefer therapy groups.)

However, even if we consider the goblet one-third full rather than two-thirds empty, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that, in this project, encounter groups did not appear to be a highly potent agent of change.

Furthermore, a significant risk factor was involved: 16 (8 percent) of the 210 subjects suffered psychological injury that produced sequelae still present six months after the end of the group.

Still, caution must be exercised in the interpretation of the results. It would do violence to the data to conclude that encounter groups per se are ineffective or even dangerous. First, it is difficult to gauge the degree to which we can generalize these findings to populations other than an undergraduate college student sample. But, even more important, we must take note that

these are all massed results

: the data are handled as though all subjects were in one encounter group. There was no standard encounter group experience; there were eighteen different groups, each with a distinct culture, each offering a different experience, and each with very different outcomes. In some groups, almost every member underwent some positive change with no one suffering injury; in other groups, not a single member benefited, and one was fortunate to remain unchanged.

The next obvious question—and one highly relevant to psychotherapy—is:

Which type of leader had the best, and which the worst, results?

The T-group leader, the gestalt, the transactional analytic leader, the psychodrama leader, and so on? However, we soon learned that the question posed in this form was not meaningful. The behavior of the leaders when carefully rated by observers varied greatly and did not conform to our pregroup expectations.

The ideological school to which a leader belonged told us little about that leader’s actual behavior.

We found that the behavior of the leader of one school—for example, gestalt therapy, resembled the behavior of the other gestalt therapy leader no more closely than that of any of the other seventeen leaders. In other words, the leaders’ behavior is not predictable from their membership in a particular ideological school.

Yet the effectiveness of a group was, in large part, a function of its leader’s behavior.

How, then, to answer the question, “Which is the more effective leadership style?” Ideological schools—what leaders

say

they do—is of little value. What is needed is a more accurate, empirically derived method of describing leader behavior. We performed a factor analysis of a large number of leader behavior variables (as rated by observers) and derived four important basic leadership functions:

1.

Emotional activation

(challenging, confronting, modeling by personal risk-taking and high self-disclosure)

2.

Caring

(offering support, affection, praise, protection, warmth, acceptance, genuineness, concern)

3.

Meaning attribution

(explaining, clarifying, interpreting, providing a cognitive framework for change; translating feelings and experiences into ideas)

4.

Executive function

(setting limits, rules, norms, goals; managing time; pacing, stopping, interceding, suggesting procedures)

These four leadership functions (emotional activation, caring, meaning attribution, executive function) have great relevance to the group therapy leadership. Moreover, they had a clear and striking relationship to outcome.

Caring and meaning attribution had a linear relationship to positive outcome

: in other words,

the higher the caring and the higher the meaning attribution, the higher the positive outcome.

The other two functions,

emotional stimulation and executive function, had a curvilinear relationship to outcome—

the rule of the golden mean applied: in other words,

too much or too little of this leader behavior resulted in lower positive outcome

.

Let’s look at leader emotional stimulation:

too little

leader emotional stimulation resulted in an unenergetic, devitalized group;

too much

stimulation (especially with insufficient meaning attribution) resulted in a highly emotionally charged climate with the leader pressing for more emotional interaction than the members could integrate.

Now consider leader

executive function: too little

executive function—a laissez-faire style—resulted in a bewildered, floundering group; too

much

executive function resulted in a highly structured, authoritarian, arrhythmic group that failed to develop a sense of member autonomy or a freely flowing interactional sequence.

The most successful leaders, then—and this has great relevance for therapy—were those whose style was moderate in amount of stimulation and in expression of executive function and high in caring and meaning attribution.

Both caring and meaning attribution seemed necessary: neither alone was sufficient to ensure success.

These findings from encounter groups strongly corroborate the functions of the group therapist as discussed in chapter 5. Both emotional stimulation and cognitive structuring are essential. Carl Rogers’s factors of empathy, genuineness, and unconditional positive regard thus seem incomplete; we must add the cognitive function of the leader. The research does not tell us

what kind of meaning attribution is essential

. Several ideological explanatory vocabularies (for example, interpersonal, psychoanalytic, transactional analytic, gestalt, Rogerian, and so on) seemed useful. What seems important is

the process of explanation,

which, in several ways, enabled participants to integrate their experience, to generalize from it, and to transport it into other life situations.

The importance of meaning attribution received powerful support from another source. When members were asked at the end of each session to report the most significant event of the session and the reason for its significance, we found that those members who gained from the experience were far more likely to report incidents involving cognitive integration. (Even so revered an activity as self-disclosure bore little relationship to change unless it was accompanied by intellectual insight.) The pervasiveness and strength of this finding was impressive as well as unexpected in that encounter groups had a fundamental anti-intellectual ethos.

The study had some other conclusions of considerable relevance to the change process in experiential groups. When outcome (on both group and individual level) was correlated with the course of events during the life of a group, findings emerged suggesting that a number of widely accepted experiential group maxims needed to be reformulated, for example:

1.

Feelings not thought

should be altered to

feelings, only with thought.

2.

Let it all hang out

is best revised to

let more of it hang out than usual, if it feels right in the group, and if you can give some thought to what it means.

In this study, self-disclosure or emotional expressiveness (of either positive or negative feelings) was not in itself sufficient for change.

3.

Getting out the anger is essential

is best revised to

getting out the anger may be okay, but keeping it out there steadily is not

. Excessive expression of anger was counterproductive: it was not associated with a high level of learning, and it generally increased risk of negative outcome.

4.

There is no group, only persons

should be revised to

group processes make a difference in learning, whether or not the leader pays attention to them.

Learning was strongly influenced by such group properties as cohesiveness, climate, norms, and the group role occupied by a particular member.

5.

High yield requires high risk

should be changed to

the risk in encounter groups is considerable and unrelated to positive gain.

The high-risk groups, those that produced many casualties, did not at the same time produce high learners. The productive groups were safe ones. The high-yield, high-risk group is, according to our study, a myth.

6.

You may not know what you’ve learned now, but later, when you put it all together, you’ll come to appreciate how much you’ve learned

should be revised to

bloom now, don’t count on later

. It is often thought that individuals may be shaken up during a group experience but that later, after the group is over, they integrate the experience they had in the group and come out stronger than ever. In our project, individuals who had a negative outcome at the termination of the group never moved to the positive side of the ledger at follow-up six months later.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE ENCOUNTER GROUP AND THE THERAPY GROUP

Having traced the development of the encounter group to the moment of collision with the field of group psychotherapy, I now turn to the evolution of the therapy group in order to clarify the interchange between the two disciplines.

The Evolution of Group Therapy