The Sword And The Olive (8 page)

Read The Sword And The Olive Online

Authors: Martin van Creveld

In Tel Aviv, at that time a more sizable town with a population of about 50,000, some 230 Hagana members immediately obeyed orders and presented themselves. The men were issued what arms were to be had—rifles, pistols, and a couple of light machine guns—and sent out to occupy positions in the various neighborhoods. There they were joined by small groups of vigilantes, often consisting of citizens who had served in the Jewish battalions or else of high-school students. Some brought along their own unregistered and unlicensed pistols, whereas others came with homemade swords, axes, and the like. The two “armies” faced each other across the agricultural space then separating Tel Aviv from Jaffa. From time to time a British armored car would appear on the scene, firing into the air and causing both Jews and Arabs to run for cover before it moved somewhere else. Later these patrols became more frequent, putting a cap on the disturbances, which became increasingly limited to potshots.

In fact the British, even though taken by surprise and requiring time to get organized, reacted credibly enough. On the afternoon of August 27 the first reinforcements in the form of 400 Royal Marines aboard the warship

Barham

reached Haifa from Malta; their arrival sufficed to overawe the city, which quickly began returning to normal. Elsewhere, too, the appearance of disciplined British units, even those with few troops, was usually enough to disperse the crowds. At the end of six days 133 Jews and 116 Arabs had been killed, 339 and 232 wounded; whereas almost all Jewish casualties were caused by Arab rioting and sniping, most Arab casualties were inflicted by organized units of British and British-commanded troops. Order in the towns was quickly restored, although operations aimed at suppressing small-scale guerrilla activity in the countryside took much longer and were ongoing six months later. Eventually some 1,300 people were put on trial, most of them Arabs but including a few Jews as well. Twenty-six Arabs and three Jews were sentenced to death, but most of the sentences were later commuted; three Arabs actually hanged.

Barham

reached Haifa from Malta; their arrival sufficed to overawe the city, which quickly began returning to normal. Elsewhere, too, the appearance of disciplined British units, even those with few troops, was usually enough to disperse the crowds. At the end of six days 133 Jews and 116 Arabs had been killed, 339 and 232 wounded; whereas almost all Jewish casualties were caused by Arab rioting and sniping, most Arab casualties were inflicted by organized units of British and British-commanded troops. Order in the towns was quickly restored, although operations aimed at suppressing small-scale guerrilla activity in the countryside took much longer and were ongoing six months later. Eventually some 1,300 people were put on trial, most of them Arabs but including a few Jews as well. Twenty-six Arabs and three Jews were sentenced to death, but most of the sentences were later commuted; three Arabs actually hanged.

The events of 1929 were to prove a turning point in the history of Hagana and, with it, of the yet to be born Israeli Defense Force. Speaking in public, the

Yishuv

’s leaders, many of whom were conveniently out of the country at the time the troubles broke out, were ecstatic about the heroism displayed by their fellow citizens; thus, Ben Gurion as chairman of Histadrut claimed that Hagana “had saved our people from destruction” and demanded that it be “further fortified.” In private, however, they were much less laudatory, savaging it for failing to protect Hebron and Safed in particular. Organization, training, armaments, and readiness all came under critical fire—by the same politicians, needless to say, who throughout the twenties had starved Hagana of funds.

Yishuv

’s leaders, many of whom were conveniently out of the country at the time the troubles broke out, were ecstatic about the heroism displayed by their fellow citizens; thus, Ben Gurion as chairman of Histadrut claimed that Hagana “had saved our people from destruction” and demanded that it be “further fortified.” In private, however, they were much less laudatory, savaging it for failing to protect Hebron and Safed in particular. Organization, training, armaments, and readiness all came under critical fire—by the same politicians, needless to say, who throughout the twenties had starved Hagana of funds.

After two years of ugly squabbling, including a minor “commanders’ revolt,” these criticisms finally led to Hecht’s forced resignation (although in practice without real authority, as the organization’s titular head he was the natural scapegoat; at the same time, paradoxically, he was blamed for trying to do too much on his own without consulting the rest). Control of Hagana passed from the Histadrut to the Zionist executive as the highest directing body both of the Jewish Agency and of world Zionism. From 1935 on, the head of both bodies was David Ben Gurion, who thus assumed overall responsibility for the community’s political and military fortunes. Day-to-day control was exercised by a five-man committee; two members represented Histadrut, two the towns, and one the collective settlements. The guiding spirit remained Eliyahu Golomb, the archtypical party activist who had thus rid himself of his principal rival. Yet however modest Hecht’s achievements, his term of office marked the real foundation of the first Jewish armed force to serve the Jewish people in nearly two thousand years

.

.

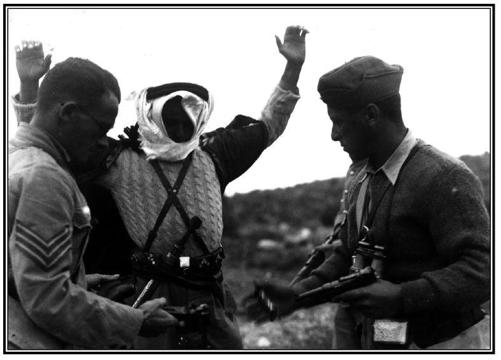

“Beyond the Fence”: Hagana detachment searching Arab marauder, 1938.

CHAPTER 3

“BEYOND THE FENCE”

F

OR BRITAIN THE events in Palestine, a small province that straddled British communications between the Suez Canal and their much more important holdings in Iraq, acted as a warning. The number of troops stationed in the country was increased to two battalions; additional British policemen were also recruited until their number reached 744 in 1935, in addition to 1,452 Arab and 282 Jewish auxiliary police. New roads were built, particularly one linking Acre with Safed that for the first time opened western Galilee, heretofore an area crossed only by goats, to the movements of modern armed forces. A professional police officer named Herbert Dowbigin was brought in from Ceylon to investigate and submitted a new plan for policing the country.

1

OR BRITAIN THE events in Palestine, a small province that straddled British communications between the Suez Canal and their much more important holdings in Iraq, acted as a warning. The number of troops stationed in the country was increased to two battalions; additional British policemen were also recruited until their number reached 744 in 1935, in addition to 1,452 Arab and 282 Jewish auxiliary police. New roads were built, particularly one linking Acre with Safed that for the first time opened western Galilee, heretofore an area crossed only by goats, to the movements of modern armed forces. A professional police officer named Herbert Dowbigin was brought in from Ceylon to investigate and submitted a new plan for policing the country.

1

These and other measures notwithstanding, the British were aware that they could not be everywhere at once. They therefore once again engaged Hagana in talks to see how the

Yishuv

might be made to do more in its own defense without, of course, endangering imperial rule. Various plans were discussed but, in the end, came to very little. The only measure actually taken was to distribute 585 rifles, each with 50 rounds, to various Jewish settlements throughout the country; considering that there were already well in excess of a hundred settlements, this didn’t amount to much. The rifles and rounds were contained in sealed boxes and, to make sure they were still there, inspected by British officers who came by once a year. The idea was that they should be used only in an emergency.

Yishuv

might be made to do more in its own defense without, of course, endangering imperial rule. Various plans were discussed but, in the end, came to very little. The only measure actually taken was to distribute 585 rifles, each with 50 rounds, to various Jewish settlements throughout the country; considering that there were already well in excess of a hundred settlements, this didn’t amount to much. The rifles and rounds were contained in sealed boxes and, to make sure they were still there, inspected by British officers who came by once a year. The idea was that they should be used only in an emergency.

Thus left to its own devices, Hagana set out to rebuild and expand its forces. Galvanized into action by the riot emergency, Zionist organizations abroad launched a fund drive. By the end of 1929 they had collected 800,000 Palestinian pounds, equivalent to the same sum in British pounds and to five times that sum in U.S. dollars (and this at a time when the average annual income of an Arab peasant family stood at 27 pounds).

2

The money was well spent. Destroyed settlements were rebuilt and others fortified by adding patrol roads, fences, searchlights, shelters, and the like. Attempts were made to analyze the lessons of the recent events including, in particular, the need for better training, an efficient intelligence organization, and improved communications between Hagana headquarters and the settlements and among the settlements themselves.

2

The money was well spent. Destroyed settlements were rebuilt and others fortified by adding patrol roads, fences, searchlights, shelters, and the like. Attempts were made to analyze the lessons of the recent events including, in particular, the need for better training, an efficient intelligence organization, and improved communications between Hagana headquarters and the settlements and among the settlements themselves.

While the rest of the world was caught in the Great Depression, for the Jewish community in Palestine the early thirties were once again years of unprecedented economic and demographic growth. In 1924 the United States had imposed its immigration law, effectively closing the most important country in which Jews had been settling since the late nineteenth century. The shadow of national socialism was darkening Europe, and hundreds of thousands were leaving. Between 1931 and 1936 the Jewish population in Palestine grew from 175,000 to 400,000. Not only were the newcomers better educated and wealthier than their predecessors, but most of them were younger, with the result that the proportion of males of military age (fifteen to forty-nine) was actually larger than that among the Arabs.

3

Eighty percent of the immigrants went to the three large towns of Haifa, Jerusalem, and especially Tel Aviv, which tripled its population to 150,000 and thus accounted for 40 percent of the total population.

4

Outlying areas also benefited. Between 1920 and 1937 an additional 683,000

dunam

of land passed into Jewish hands. Consequently all Jewish holdings combined now amounted to 1.33 million

dunam

, approximately 5 percent of the total area west of the River Jordan and perhaps 8 percent of the area that eventually would become the state of Israel.

5

3

Eighty percent of the immigrants went to the three large towns of Haifa, Jerusalem, and especially Tel Aviv, which tripled its population to 150,000 and thus accounted for 40 percent of the total population.

4

Outlying areas also benefited. Between 1920 and 1937 an additional 683,000

dunam

of land passed into Jewish hands. Consequently all Jewish holdings combined now amounted to 1.33 million

dunam

, approximately 5 percent of the total area west of the River Jordan and perhaps 8 percent of the area that eventually would become the state of Israel.

5

In 1931, after a two-year hiatus, Hagana once more received a titular head in the person of Saul Avigur (originally Meirov). Russian-born like the rest, thirty-two years old at the time, he had been raised in Tel Aviv and gained his spurs by helping guard various northern settlements during the twenties as well as smuggling arms from Syria and Lebanon. He set up his headquarters in Room 33 of Histadrut’s main building on Allenby Street, Tel Aviv, a handy arrangement for communicating with other activists and for avoiding prying Britons. A list of members and an inventory of available resources were drawn up. It brought to light an incredible assortment of arms, many of them antiquated or in bad repair, with or without ammunition to match. Though regularly updated thereafter, the inventory even under the best circumstances was by no means complete. Many settlements concealed their assets not only from the British but also from their superiors in Hagana.

6

This was not a surprising reaction, given Hagana’s recently demonstrated inability to move resources around the country or provide aid in an emergency.

6

This was not a surprising reaction, given Hagana’s recently demonstrated inability to move resources around the country or provide aid in an emergency.

The tendency to conceal arms reflected a deeper dilemma already familiar from Ha-shomer days, namely, whether Hagana was to be a countrywide, centralized, and disciplined organization under a single command or merely a loose coalition between local self-defense groups, each of which looked after the needs of its own settlement or town. Avigur, needless to say, stood for the former interpretation. In 1934 he drafted a document known as “The Foundations of Defense” (

Oshiot Ha

-

hagana

). In it he emphasized that Hagana was the sole organization responsible for Jewish self-defense as well as the need to combat any attempt to set up alternative groups. It was to be run along military lines, with a recognized chain of command, bottom-to-top accountability, and strict discipline.

7

Oshiot Ha

-

hagana

). In it he emphasized that Hagana was the sole organization responsible for Jewish self-defense as well as the need to combat any attempt to set up alternative groups. It was to be run along military lines, with a recognized chain of command, bottom-to-top accountability, and strict discipline.

7

However sensible these demands might be in theory, in practice they could not be realized. Not being a government in the formal sense of the word, the Zionist Agency did not have the authority to prevent other groups from organizing themselves; nor was the imposition of strict military discipline practicable under the prevailing conditions, in which the organization was semilegal at best. The root of the problem went deeper. Most of the leaders of Hagana and the

Yishuv

originated from eastern Europe, where they had lived under czarist rule. Jews traditionally regarded military service, indeed any kind of laws—enacted by governments usually bent on persecuting them—as things to be evaded by every possible means. Coming to Palestine, they took these qualities along; it is said that no recruits were ever as undisciplined as the volunteers for the Jewish battalions in 1917-1918.

8

The tendency to play games with the law worked at crosscurrents with a penchant for self-help (made all the more necessary by Hagana’s lack of funds and the settlements’ isolation with an almost total lack of telecommunications in the countryside).

Yishuv

originated from eastern Europe, where they had lived under czarist rule. Jews traditionally regarded military service, indeed any kind of laws—enacted by governments usually bent on persecuting them—as things to be evaded by every possible means. Coming to Palestine, they took these qualities along; it is said that no recruits were ever as undisciplined as the volunteers for the Jewish battalions in 1917-1918.

8

The tendency to play games with the law worked at crosscurrents with a penchant for self-help (made all the more necessary by Hagana’s lack of funds and the settlements’ isolation with an almost total lack of telecommunications in the countryside).

These factors created a unique military lifestyle that, whatever the manuals might say, always combined a spirit of high enterprise with rather lax discipline. A typical example was Moshe Dayan—who during his lifetime was revered partly for that very reason. Born in 1915, he was a natural warrior possessed of exceptional courage under fire, a certain peasant cunning, and many excellent ideas about how to outwit and beat the enemy. However, he and his comrades-in-arms were also quite prepared to fill their stomachs by breaking into chicken coops belonging to the neighboring

kibbutsim

;

9

indeed, “a tendency to disregard questions of law and order”

10

was said to be characteristic of Hagana commanders down to the 1948 war and beyond. So long as motivation remained strong, as it was bound to be at a time when first the Palestinian Arabs and later the much larger and more populous Arab states constituted a mortal threat to the community’s very existence, this combination of qualities proved irresistible. Still, in principle one could foresee the day when, as the intensity of the threat and with it motivation diminished, it would become positively dangerous.

kibbutsim

;

9

indeed, “a tendency to disregard questions of law and order”

10

was said to be characteristic of Hagana commanders down to the 1948 war and beyond. So long as motivation remained strong, as it was bound to be at a time when first the Palestinian Arabs and later the much larger and more populous Arab states constituted a mortal threat to the community’s very existence, this combination of qualities proved irresistible. Still, in principle one could foresee the day when, as the intensity of the threat and with it motivation diminished, it would become positively dangerous.

During 1930-1935, though, such a situation was still very far in the future. Under its new leader, Hagana’s overriding purpose was to obtain additional arms. Agents were sent to Belgium, France, and Italy, the former two because controls were lax and the last because the fascist government was often prepared to overlook Jewish activities that it judged to be anti-British. (In 1935-1937 the port of La Spezia even hosted the first-ever course for naval personnel to be held by Hagana.) Arms and ammunition were purchased and packed into crates and suitcases as if forming part of the baggage of new immigrants; others were stored in barrels marked “cement.” Shipped to Jaffa and later to the new port at Haifa, they were smuggled through customs by Jewish officials who cooperated and by Arab ones who were bribed. From time to time there was a leak, either an accidental one as a case hit the floor and broke or when somebody noticed and told. The resulting interruptions were, however, seldom serious and did not halt the flow for long.

Other books

The Herbalist by Niamh Boyce

The Gallant by William Stuart Long

Lethal Legacy by Louise Hendricksen

Howzat! by Brett Lee

Doing It at the Dixie Dew by Moose, Ruth

Beneath the Sands of Egypt by Donald P. Ryan, PhD

The Moon and the Sun by Vonda N. McIntyre

Earth Bound by Avril Sabine

Stone Cold Cowboy by Jennifer Ryan

(2013) Four Widows by Helen MacArthur