The Sword And The Olive (25 page)

Read The Sword And The Olive Online

Authors: Martin van Creveld

Thus, militarily speaking the feature usually seen as the single most original characteristic of the IDF—the conscription of women—has in reality been less important than is commonly thought. It has also given rise to many misunderstandings, which is why I have discussed it at some length. Somewhat less original, but much more important, was the system of officer selection, training, and promotion, including its heavy emphasis on proven competence, military experience, and youth and its corresponding neglect of social origin, formal education, and military affectations (such as shoulder straps and gloves). These characteristics apart, the IDF represented not so much an original creation as a typical modern armed force modeled on, and in many ways resembling, those of the principal twentieth-century European states (although, owing to a combination of inexperience and poverty, during the first half of the fifties its organization and equipment still left much to be desired).

Like the forces of other developed countries the IDF was trinitarian, that is, a corporate entity clearly separate from the government on the one hand and the people on the other. Like the forces of other developed countries it was supported by a ministry of defense; its principal role, small by comparison with some others, was to organize the civilian aspects of defense and procure arms for it. Less than the forces of most developed countries it was subject to civilian, particularly parliamentary control. More than them it took overall responsibility for the country’s security including, in particular, intelligence; to be routinely called to report to the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee is a privilege that no other Western military intelligence chief enjoys. More than them, too, it had a unified general staff in full command of the three services. Unable to support large forces in peace, it was divided into long-serving professionals, short-serving conscripts, and reservists—an arrangement typical of the majority of the world’s greatest armed forces (Britain and the United States alone excepted) from 1871 on.

70

From the early 1950s on, it also developed a strategic-operational doctrine that, in light of the enemies it was facing, was designed to use all these characteristics to the best effect.

70

From the early 1950s on, it also developed a strategic-operational doctrine that, in light of the enemies it was facing, was designed to use all these characteristics to the best effect.

Nevertheless, in the end analysis these are matters of detail. Overshadowing them, and making the entire system possible, was the unique position of the IDF in the eyes of Israeli society. It is comparable, if at all, only to the status the armed forces held in Germany from 1871 until 1945.

71

The IDF was seen as the one great institution around which a young and heterogeneous nation could rally. This included not only old inhabitants and new immigrants but also right- and left-wing parties; and the situation where the latter were suspicious of the military for reasons of class (as in France around the turn of the century) hardly arose. Though differences in emphasis did exist, perhaps the only Israelis who resolutely opposed the military and all it represented were the

charedim

(non-Zionist orthodox Jews). Then as now they formed a world apart—in no small measure for that very reason.

71

The IDF was seen as the one great institution around which a young and heterogeneous nation could rally. This included not only old inhabitants and new immigrants but also right- and left-wing parties; and the situation where the latter were suspicious of the military for reasons of class (as in France around the turn of the century) hardly arose. Though differences in emphasis did exist, perhaps the only Israelis who resolutely opposed the military and all it represented were the

charedim

(non-Zionist orthodox Jews). Then as now they formed a world apart—in no small measure for that very reason.

The attempt, dating back two or three decades but only now getting into high gear, to create a new type of Jew who would be prepared to defend himself—not to say trigger-happy—had been only too successful. The War of Independence represented the first Jewish victory in more than two thousand years. No wonder Israeli public opinion happily rid itself of traditional Jewish pacifism and fell madly in love with everything military; particularly in

kibbutsim

the social pressure on young males to join combat units and distinguish themselves was well-nigh intolerable, driving some who did not measure up to suicide.

72

When the new state celebrated its first anniversary, in May 1949, the 300,000 people (one-third of the entire population!) who gathered to watch the IDF parade in Tel Aviv were so enthusiastic that they blocked the route, prevented the march-past from being completed, and turned the festivities into a mess.

73

Lesson learned, the next time the IDF put itself on display the troops looked and acted like tin soldiers, as one newspaper proudly proclaimed.

74

From then until 1968 every single Yom Atsmaut (Independence Day) centered around the inevitable march-past. It was held in various cities in rotation and often welcomed by elevating messages such as “Rejoice Tel Aviv, at TSAHAL entering thine gates.”

kibbutsim

the social pressure on young males to join combat units and distinguish themselves was well-nigh intolerable, driving some who did not measure up to suicide.

72

When the new state celebrated its first anniversary, in May 1949, the 300,000 people (one-third of the entire population!) who gathered to watch the IDF parade in Tel Aviv were so enthusiastic that they blocked the route, prevented the march-past from being completed, and turned the festivities into a mess.

73

Lesson learned, the next time the IDF put itself on display the troops looked and acted like tin soldiers, as one newspaper proudly proclaimed.

74

From then until 1968 every single Yom Atsmaut (Independence Day) centered around the inevitable march-past. It was held in various cities in rotation and often welcomed by elevating messages such as “Rejoice Tel Aviv, at TSAHAL entering thine gates.”

Enthusiasm for things military also manifested itself on a day-to-day basis. Anthologies of Jewish heroic deeds, past and present, were printed and often went into many editions owing to their popularity as bar-mitsva presents and the like.

75

Martial songs, many of them with Hebrew words fitted to Russian tunes, were constantly broadcast on civilian and the IDF’s radio stations. “How beautiful is the squad, marching through the mountains,” one of them went. “Go out into the streets of the

moshava

, girls, soldiers are coming!” constituted almost the entire lyrics of another. A third took its inspiration from the colorful language used by NCOs to address their soldiers. One should not underestimate the importance of mere songs. On the contrary, given the massive immigration of those years, they were widely seen and deliberately used as vehicles for creating social cohesion where none had previously existed.

76

Doing so was among the missions of the military entertainment troupes that amused civilian and military audiences with songs and sketches about army life. For many years thereafter membership in these troupes (a phenomenon entirely unknown in other Western countries, where military entertainment stands to entertainment as military cooking stands to the chef’s art) was often considered a good visiting card for youngsters seeking to enter Israeli show business.

75

Martial songs, many of them with Hebrew words fitted to Russian tunes, were constantly broadcast on civilian and the IDF’s radio stations. “How beautiful is the squad, marching through the mountains,” one of them went. “Go out into the streets of the

moshava

, girls, soldiers are coming!” constituted almost the entire lyrics of another. A third took its inspiration from the colorful language used by NCOs to address their soldiers. One should not underestimate the importance of mere songs. On the contrary, given the massive immigration of those years, they were widely seen and deliberately used as vehicles for creating social cohesion where none had previously existed.

76

Doing so was among the missions of the military entertainment troupes that amused civilian and military audiences with songs and sketches about army life. For many years thereafter membership in these troupes (a phenomenon entirely unknown in other Western countries, where military entertainment stands to entertainment as military cooking stands to the chef’s art) was often considered a good visiting card for youngsters seeking to enter Israeli show business.

Besides the standard fare of roses, rainbows, and kissing couples, the greeting cards Israelis sent on New Year’s Day (Rosh Hashanah) often carried pictures of IDF soldiers, jeeps, tanks, combat aircraft, and warships (as did packs of chewing gum, matchbox covers, cigarette packs, etc.). As happened, for example, in the United States after the Civil War and in Germany after World War I, elders used their onetime heroism to lord it over youngsters. The latter, branded first as

brarah

(offal) and later as the “espresso generation,” sought to emulate the former, perhaps most notoriously by means of unauthorized hikes into enemy territory, during which a number were killed. Two journalists published a collection of “Tall PALMACH Tales” in 1953, which quickly became a best-seller.

77

At Purim, the Israeli equivalent of Halloween, no costume was more popular than that of an IDF soldier. The greatest compliment anyone could receive was that he was a “fighter.” Military-style boots were known, somewhat sarcastically, as “heroes’ shoes.”

brarah

(offal) and later as the “espresso generation,” sought to emulate the former, perhaps most notoriously by means of unauthorized hikes into enemy territory, during which a number were killed. Two journalists published a collection of “Tall PALMACH Tales” in 1953, which quickly became a best-seller.

77

At Purim, the Israeli equivalent of Halloween, no costume was more popular than that of an IDF soldier. The greatest compliment anyone could receive was that he was a “fighter.” Military-style boots were known, somewhat sarcastically, as “heroes’ shoes.”

Far from being mere spontaneous manifestations of popular culture, these attitudes were systematically fostered by the authorities. In the Knesset, Ben Gurion thundered about the need to use the army as a vehicle for creating a race of warrior-settlers who would work the land by day and stand guard at night.

78

At a less elevated level, the mayor of Ramat Gan near Tel Aviv used to address hundreds of graduates every year. He was a big-bodied Hagana veteran (while serving in the Ottoman army during World War I he had distinguished himself by stealing the molds of a hand grenade, thus permitting self-manufacture to get under way). In his heavily Russian-accented Hebrew he wished for his audience that they would “become soldiers—heroes—good luck!”

78

At a less elevated level, the mayor of Ramat Gan near Tel Aviv used to address hundreds of graduates every year. He was a big-bodied Hagana veteran (while serving in the Ottoman army during World War I he had distinguished himself by stealing the molds of a hand grenade, thus permitting self-manufacture to get under way). In his heavily Russian-accented Hebrew he wished for his audience that they would “become soldiers—heroes—good luck!”

Combined, as they frequently were, with the usual Israeli penchant for indiscipline and slovenliness, in retrospect many of the manifestations of militarism that were characteristic of those years appear ludicrous. At the time they reflected and created exceptionally high morale, which, as Napoleon said, is to the physical aspects of war as three to one. The IDF’s successes, like those of armed forces in other countries, can never be understood without reference to its exalted position in the public mind. The public mind itself was the product of the feeling of

en brera

(no choice), the importance of which in Israeli history cannot be exaggerated.

en brera

(no choice), the importance of which in Israeli history cannot be exaggerated.

En brera

rested on the balance of forces. That balance was summed up in the twin concepts of

i katan be-toch yam arvi

(a small island in an Arab sea) and

meatim mul rabbim

(the few against the many), both born before independence and serving the state well thereafter. It is true that as of late 1948 the IDF outnumbered all its enemies combined; and since then it has often possessed superior weapons and firepower. Yet during much of Israel’s history the perceived ratio of its armed forces to those of neighboring countries has been on the order of one to three. Behind the myth, carefully cultivated by Ben Gurion

79

and others, of a small and hopelessly exposed state surrounded by potentially much stronger enemies—enemies bent on destroying it, no less—there existed a solid reality. For decades on end it was not so much doctrine, organization, training, technology, or whatever but

en brera

and the sense of utter determination that it generated that provided the real dynamo behind Israeli military prowess. Perhaps it was predictable that, if it went, everything else would go as well.

rested on the balance of forces. That balance was summed up in the twin concepts of

i katan be-toch yam arvi

(a small island in an Arab sea) and

meatim mul rabbim

(the few against the many), both born before independence and serving the state well thereafter. It is true that as of late 1948 the IDF outnumbered all its enemies combined; and since then it has often possessed superior weapons and firepower. Yet during much of Israel’s history the perceived ratio of its armed forces to those of neighboring countries has been on the order of one to three. Behind the myth, carefully cultivated by Ben Gurion

79

and others, of a small and hopelessly exposed state surrounded by potentially much stronger enemies—enemies bent on destroying it, no less—there existed a solid reality. For decades on end it was not so much doctrine, organization, training, technology, or whatever but

en brera

and the sense of utter determination that it generated that provided the real dynamo behind Israeli military prowess. Perhaps it was predictable that, if it went, everything else would go as well.

CHAPTER 9

TRIALS BY FIRE

T

HOUGH THE 1949 armistice agreements put an end to large-scale warfare with the Arab countries, small-scale fighting with the Palestinians—principally those who had recently become refugees—continued. The forced flight of approximately 600,000 people had left entire districts more or less empty. Even before the war ended, abandoned fields were being taken over by Israeli individuals and communal settlements (which often claimed and usually obtained Arab-owned plots and the crops they contained) and the government. Watching the process from improvised camps in Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, the former owners could not but feel resentment and anger at the great material and physical losses. Yet the fact that most of the state’s newly established borders did not rest on any geographical features and were, indeed, often unmarked on the ground encouraged infiltration.

HOUGH THE 1949 armistice agreements put an end to large-scale warfare with the Arab countries, small-scale fighting with the Palestinians—principally those who had recently become refugees—continued. The forced flight of approximately 600,000 people had left entire districts more or less empty. Even before the war ended, abandoned fields were being taken over by Israeli individuals and communal settlements (which often claimed and usually obtained Arab-owned plots and the crops they contained) and the government. Watching the process from improvised camps in Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, the former owners could not but feel resentment and anger at the great material and physical losses. Yet the fact that most of the state’s newly established borders did not rest on any geographical features and were, indeed, often unmarked on the ground encouraged infiltration.

Then and later, the motives of the

mistanenim

(infiltrators) varied.

1

Some were armed, but the majority were not. Some merely made brief journeys across the border to visit relatives who stayed behind or to save property such as crops, livestock, and whatever else survived expropriation and could be readily removed. Others planned to make a more permanent return to former homes, and still others came with the deliberate intent of taking revenge. The latter stole livestock, destroyed agricultural equipment, blocked wells, and attacked people; there were woundings, killings, mutilations (to bring back proof of their actions), and, very occasionally, rapes. The establishment of Israel had severed some of the region’s traditional trade routes, particularly those between Egypt and Jordan, which were now separated by the Negev Desert. For this reason, and because in Israel basic foodstuffs were subsidized and therefore much cheaper than in neighboring countries, many infiltrators smuggled goods. Finally, although most acted on their own initiative, a certain percentage worked for the intelligence services of Syria, Egypt, and Jordan in particular.

mistanenim

(infiltrators) varied.

1

Some were armed, but the majority were not. Some merely made brief journeys across the border to visit relatives who stayed behind or to save property such as crops, livestock, and whatever else survived expropriation and could be readily removed. Others planned to make a more permanent return to former homes, and still others came with the deliberate intent of taking revenge. The latter stole livestock, destroyed agricultural equipment, blocked wells, and attacked people; there were woundings, killings, mutilations (to bring back proof of their actions), and, very occasionally, rapes. The establishment of Israel had severed some of the region’s traditional trade routes, particularly those between Egypt and Jordan, which were now separated by the Negev Desert. For this reason, and because in Israel basic foodstuffs were subsidized and therefore much cheaper than in neighboring countries, many infiltrators smuggled goods. Finally, although most acted on their own initiative, a certain percentage worked for the intelligence services of Syria, Egypt, and Jordan in particular.

However understandable the infiltrators’ motives, no state can tolerate a situation whereby its borders are violated hundreds of times a year by thousands of people,

2

particularly if some are armed and attack property and citizens. From 1949 to 1956 two hundred to three hundred Israelis were killed by

mistanenim

, most in border settlements near the Gaza Strip or along the Israel-Jordan border, but some in the very heart of the country—which in any case was never very far from one border or another.

3

The number of Israelis wounded was 500-1,000; though no authorized figures estimate damage suffered, it must have amounted to many millions of Israeli pounds (an Israeli pound was worth $.55).

4

Even greater were the costs of security measures put in place, working days lost, and the general disruption and demoralization that followed.

2

particularly if some are armed and attack property and citizens. From 1949 to 1956 two hundred to three hundred Israelis were killed by

mistanenim

, most in border settlements near the Gaza Strip or along the Israel-Jordan border, but some in the very heart of the country—which in any case was never very far from one border or another.

3

The number of Israelis wounded was 500-1,000; though no authorized figures estimate damage suffered, it must have amounted to many millions of Israeli pounds (an Israeli pound was worth $.55).

4

Even greater were the costs of security measures put in place, working days lost, and the general disruption and demoralization that followed.

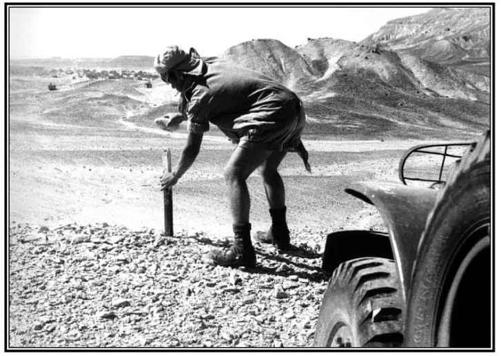

Trials by Fire: marking the road into Sinai, 1956.

The Israelis responded on three levels. The first, elementary response was to establish new settlements on the border—on the theory (promoted by Ben Gurion)

5

that the presence of Jewish populations would deprive infiltrators of freedom of movement. Most of the settlements were inhabited by new immigrants, but a few were founded by so-called

garinim

(cores) of young IDF conscripts. The latter were inducted into a special corps known as NACHAL (Noar Chalutsi Lochem, or Fighting-Pioneer Youth). After basic training they spent their military service working on a

kibbuts

and, after discharge, usually stayed on as civilians.

5

that the presence of Jewish populations would deprive infiltrators of freedom of movement. Most of the settlements were inhabited by new immigrants, but a few were founded by so-called

garinim

(cores) of young IDF conscripts. The latter were inducted into a special corps known as NACHAL (Noar Chalutsi Lochem, or Fighting-Pioneer Youth). After basic training they spent their military service working on a

kibbuts

and, after discharge, usually stayed on as civilians.

Other books

Glitches by Marissa Meyer

Dirty Neighbor (The Dirty Suburbs) by Miller,Cassie-Ann L.

The Cave by José Saramago

Magic for Beginners: Stories by Kelly Link

Con la Hierba de Almohada by Lian Hearn

The Ferryman by Christopher Golden

The Scavengers by Michael Perry

Bartolomé by Rachel vanKooij

Hounds of God by Tarr, Judith

Desperado by Diana Palmer