The Sweet Smell of Psychosis (5 page)

Read The Sweet Smell of Psychosis Online

Authors: Will Self

Richard looked on from where he was slumped. Would she give some indication that she was sorry to have missed their rendezvous, that this was an unwanted and hateful turn of events? She did, in the form of lifting

up the fingers of one hand, pushing them in his direction, and chafing the two middle ones together.

Much, much later that evening, the clique were encabbed and heading east. There had been some calls for a trip to a restaurant, but Mearns – whose party, after all, it was – had already had dinner with Pablo (the clique's preferred euphemism – this month – for doing cocaine), and couldn't be bothered, as he put it, with ‘paying x quid cover charge, x quid service charge, and twenty-bloody-x for food to play patty-cake with – rather than eat’. Once the other cliquers had snacked with Mr Escobar as well, they didn't argue.

Mearns's greenmail party had begun the same way as any other cliquey evening at the Sealink, continued the same way as any cliquey evening at the Sealink, and was now speedily moving towards a dénouement of crushing obviousness: they were going to Limehouse to smoke opium.

Bell was up front, speaking to the cab driver. Richard and Mearns sat in the back, either side of Ursula, while the others were following in another cab. It had taken masterly powers of anticipation, of jockeying, for Richard to get this close to Ursula. Not that she

was ignoring Richard any more than usual – she was simply ignoring him.

The cabbie – who was a middle-aged Syrian man with a Colonel Blimpish moustache, beach-ball paunch and shattered air – was telling Bell a long and involved story, haltingly and with real feeling, about his imprisonment and torture for an attempt on the life of President Assad. Bell appeared to be concentrating deeply on the story. He studied the cabbie's pained face intently, nodding, uttering tiny, encouraging grunts. But it was difficult for Richard to hear everything, because the radio was on and tuned to Bell's own phone-in show. This, as usual, was being dominated by Bell, berating callers, inciting callers, ignoring callers. The broadcast Bell and the in-car Bell stood proxy for each other.

Richard thought it queer, but Ursula and Mearns seemed not to have noticed. He was telling her about the last time he'd smoked opium, with triplet thirteen-year-old prostitutes in Patpong. Richard could feel Ursula's ribs move against his when she sniggered. The fulsome aroma of Jicki was thick in the enclosed atmosphere. If there had been a Magic Tree car air-freshener that distilled the odour of Ursula, it would have been called ‘Fuck Fragrance’. Richard's cock was like an iron girder

some pile-driver had rammed into his crotch. He tried to concentrate on what the driver was saying. It was a tale of courage, warmth and fortitude in the face of craven, cold brutality. The cabbie had been an air-force general. He had been befriended by Assad's brother. There had been high-living times in Switzerland. Tarts and Krug. The general had become disgusted by the decadence. He had fomented a coup. He'd ended up in jail for twelve years. Beaten on the feet. Beaten on the balls. Screwed up by his thumbs.

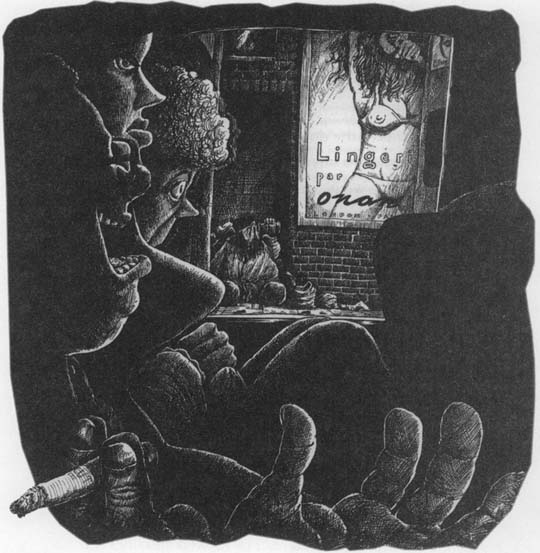

The juxtaposition of this and the squealing, coked-up atmosphere that had prevailed among the clique since they left the Sealink was grotesque. Richard felt sickened. Bell went on nodding sympathetically. The cab oozed across town. As they stopped by the lights at the junction with Kingsland Road, Richard looked to his left to see, framed between the concrete stanchion of a bus stop and the quivering bum of a double-decker, a lingerie advert that featured a young woman of such astonishing, bursting pulchritude (her mons, her nipples straining, yet demure) that Richard feared for his trousers.

But beyond the bus stop, in a door adrift with litter, sat a double amputee drinking a can of Enigma lager.

Richard looked deep into the stumps levelled in his direction, capped off with leather stump-protectors. Or, as Richard thought to himself footless boots. He tried to imagine his cock amputated, a leather stump-protector grinding into his groin. He sensed his twanging erection subside a little. The cab oozed on.

The two vehicles carrying Bell's clique arrived at Milligan Street, behind the Limehouse Causeway, at exactly the same time, and their occupants debouched into the windy road, Things had got drizzly in London – as they often do; a chilly, wet tongue of leaf blew against Richard's cheek. He looked up to see no tree, but the Legoland edifice of Canary Wharf looming overhead, its aircraft-warning beacon making a dim, provincial disco of the metropolitan night. Bell gave his account number to the cabbie, signed the clipboard where the formerly-screwed thumb indicated. Once Assad's failed assassin had driven off Richard said to Bell, ‘What did you think of that? Pretty amazing story.’

‘What story?’

‘About Assad, about Syria – what the cabbie was saying.’

‘Oh that – to be frank I wasn't paying much attention; I wanted to listen to tonight's show.

There could be comeback over what I said about wassername.’

‘Who?’

‘That soap star.’

Bell broke away from Richard and mounted the short flight of stairs to the door of the house in front of them. Richard turned to Ursula, who was coming up behind. ‘Did you hear what the cabbie was saying? Any of it?’

‘What?’

‘About Assad, about torture?’ Richard couldn't believe that he was getting carried away like this, that he was attempting to pierce the superficial skin of the evening.

‘Yeah, some. Grisly, huh?’ Ursula groped in her bag for a cigarette. Her jaw worked, chewing the cocaine cud of nothing.

‘I should say so. It's awful to think of things like that happening in the world, and we just go on talking about

nothing,

doing

nothing,

just writing on the wallpaper. Doesn't it make you feel sick sometimes?’

Ursula's jaw stopped working for a moment. She gave Richard a level stare. He looked into her eyes and saw there what he was always looking for: that she understood. That she really understood. That she

knew this wasted go-round was just that; and that she – like Richard – had higher aspirations. Aspirations to a life that might appear dull, conventional, to Bell and his clique, but which was in fact full of love, security, trust – the important values. Ursula reached out a hand and gently rumpled Richard's blond curls. ‘You know what?’ she said.

‘W-what?’

‘You're sweet.’

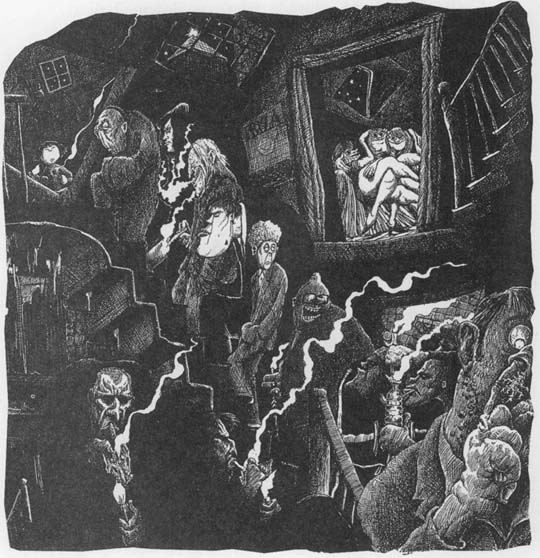

The old Chinaman who let them into the mouldering house seemed to be well known to Bell. He asked after the man's grandchildren, made reference to certain mutual business acquaintances. While this went on the rest of the clique remained backed up in the vestibule. Eventually they all shuffied on in. It was a warped, early-nineteenth-century house. At one time it would have been part of the old Limehouse rookery, a teeming, tri-dimensional dying space of interconnected alleys, courtyards and tenements; but now it stood alone, carved out from the past, teetering on the edge of the Docklands Enterprise Zone.

The Chinaman led them through rooms that had not so much been decorated, as arrived naturally at a

bewildering number of styles. Some were hung with Persian carpets, others had pop posters tacked on the walls, still more were strip-lit and tiled, like toilets or Moroccan cafes. Everywhere the atmosphere was dank, dilapidated; and everywhere there were people taking drugs. Two Iranians sat on phallic bolsters, moodily chasing the dragon; on a velveteen-covered divan a gaggle of giggling upper-class girls – as out of their element as gorillas in Regent's Park – were high on E, stroking each other's hair; and as the clique climbed the stairs, they passed two black guys smoking crack in a pipe made from a Volvic bottle. ‘I prefer Evian myself,’ Mearns sneered as they tromped by.

‘Whassit t'you, cunt?’ came back at him; but the speaker's companion muttered, ‘Safe, Danny,’ and they let it lie.

Later, Richard could barely recall the actual opium-smoking. It had taken place in an attic room, the sloping ceiling forcing the cliquers into a series of staggered postures, from upright to crouched to supine. The Chinaman spawned a daughter – or granddaughter, or great-granddaughter – who looked about eleven, and who did the business of priming the pipe, passing it round, cleaning out the dross, repeating the operation.

Richard glared at Ursula, who was allowing Bell to cup the back of her head and guide the pipe's thick stem into her mouth. The image had an awful implication. Richard concentrated on the cracked paint of the skirting board, the furring of dust on the lampshade. Outside in the street a dog was shouting at a barking drunk. The thick, sweet, organic smoke filled the room. Like agitated children being given a narcotic bedtime narrative, the cliquers were calmed as it did the rounds.

Then, the black guy from the stairs crashed in, smacked Mearns in the mouth and ran out. There was less pandemonium than might have been expected. Bell exited the room and found the Chinaman, who in turn got hold of his minder, a big Maltese guy called Vince whose nose had been cut in half and badly sewn together again.

The Chinaman ushered them all back down through the warren of rooms, with much solicitous cooing. Bell was saying ‘No matter . . . No matter . . .’ in such a way, Richard understood, as to make the Chinaman feel that it mattered a great deal, and that something

had

to be done.

More cabs were waiting outside – someone must

have used their mobile. The clique encabbed. As they pulled away from the house Richard saw the black guy. He was halfway down the area steps, and Vince appeared to be throttling him. Or perhaps – and the thought came to Richard as painfully as a sick bubble of gaseous indigestion squeezes between waist and band – Vince was making love to him, and cutting off his carotid artery as a means of inducing shattering orgasm.

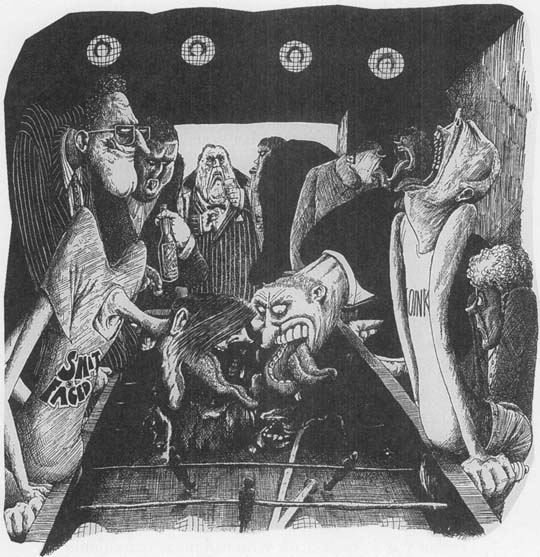

Then the Sealink again – the table-football room, to be precise. The club had bought an outsize table-football table from a paedophile member – of parliament. Now, the wannabe macho and the never gonnabe macho flexed their tethered cocks, yanked, biffed and slammed the balls. Taking up an unobtrusive position against one wall of the room, Richard got trapped behind two seats of agitated suit trousers, whose owners were – to all intents and purposes – psychically merged with the battered eight-inch figurines of cockless men that they manipulated.

Bell was over by the bar, talking to Trellet, an influential, older-generation member of the clique. Trellet was a comic actor who had made quite dumb amounts of money by impersonating a bumbling, lovable paterfamilias in an endless sitcom. In fact,

as soon as there was a wrap, Trellet's face collapsed from the expansively benign to the pettily vicious. In appearance not unlike a pocket-sized Robert Morley (

circa Beat the Devil

)

,

Trellet was possessed of appetites as sluttish as Bell's, but with an added full twist of genuine perversion.

Right now, Richard couldn't forbear from listening to them. As he did so his delicate ears, networked with the finest of bluest of veins, changed from the white-pink of shame to the deep, angry pink of impotence and anger. Trellet was telling two anecdotes with intersecting themes, which converged on his drive to humiliate anyone who crossed his path.