The Sweet Smell of Psychosis (4 page)

Read The Sweet Smell of Psychosis Online

Authors: Will Self

‘Oven gloves, actually.’

‘Ha-ha! Very good, Richard. “

Touché,

"

one might even say.

,

By God! He'd said something right! A thousand thousand pink flamingos lifted off from the volcanic lake of Richard's stomach.

‘Well, I'm afraid

I

had nothing much to get up for this morning, so I went on with the boys.’

‘W-where?’ The flamingos were machine-gunned by Nazi vivisectionists.

‘To that gay place by Charing Cross, then back to

The Hole again – Bell wanted to pick something up – then back to Bloomsbury.’

‘T-to Bell's?’

‘Yah. Then we had a gas. Bell had some of this shit called bliss. Sort of cross between smack, E and ice. You've gotta smoke it in a little pipe. Makes you feel . . . I dunno . . . Well! Like you'd imagine.

‘Anyway,’ Ursula went on, ‘Reiser had skulked off by this time, do Bell calls him up – he knows Reiser can't resist drugs – and says, “Hey Todd, wanna come back to my place and do some bliss? The whole gang's here, plus some babes who've blown in from out of town, and want to meet people in film . . .” Todd is salivating so much

I

can hear it, going “Yeah-yeah, yeah-yeah” like fucking Muttley. So Bell just says, “Well you can't!” and slams the phone down. Ha-ha-ha-ha!’

‘Hee-hee, hee-hee,’ Richard joined in, although he couldn't for the life of him have said what was funny about it.

‘The poor sap even came over and leant on the entryphone for half an hour before Bell got round to disconnecting it – ‘

‘When did you get home?’ Richard almost snapped this; like most courage, it was reflex.

‘What?’

‘I mean – back?’

‘Dunno. Whatever. Six-thirty, seven. Whatever. Tweety time, at any rate – I'm fucked. Anyway, Richard, it's Mearns's greenmail party this evening, and I'm doing the APB. See you at the Club at seven –

I'll

be early . . .’

‘O – ‘

Rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr . . .

Richard listened to the dialling tone for some time, hearing it as the Little Bear's purring, lustful breath. That's what his lovey-dovey nickname for her would be: ‘Little Bear’.

Then he shook himself out of it and turned to the computer. The screen showed the corporate screensaver, a cartoon representation of an average

Rendezvous

reader (back view), ringing with a felt tip his/her cultural-event selections for the week. Richard slapped the mouse; the screen squeaked and cleared to reveal about two hundred words of copy. With a myriad flocks of pink flamingos spiralling like galaxies in his universal heart, Richard Hermes bent to the task of correcting the copy. He had been called by Ursula Bentley! They had made . . . a rendezvous! (What else

could that ‘early’ have meant?) On such a day, even annotating pre-puff for Razza Rob's new stand-up show

Gynae-Gynae, Hey-Hey!

was a rare treat.

Richard hovered about on a metaphorical decision-making corner all day, much like the John on his actual corner the night before. At five he started for Hornsey, only to abandon the journey halfway there, leaving the tube at Archway on the grounds that he wasn't going to have enough time to get home, shower, masturbate himself into a genderless nullity (this was an evening when Richard didn't even wish for the race memory of an involuntary erection), then address the question of his toilet and attire with a rigour not seen since pubescent, preening pre-disco nightmares.

To have insufficient time at the Wendy flat would be worse than having none at all. Better to turn up at the Sealink with a devil-may-care, rumpled-from-the-night-before, funky-dirty-stopover, essentially rugged and masculine demeanour. In this macho attitude Richard would rub his stubble vigorously against Ursula's cheek upon meeting, challenging her with insolent eyes to imagine its abrasiveness applied elsewhere – sanding her into submission.

Richard's sagging, spotted trousers, bagging shirt

and scuffed shoes would be taken by Ursula as telling evidence of a disconcertingly sexy and powerful lack of self-consciousness. He considered whether a nice further touch might be to give a mock-Yiddisher hunch of his shoulders and declaim to her, ‘Style, schmyle!’

All of this kaleidoscoped through Richard's mind as he paced up and down the tatty concourse outside Archway Tower, his eyes stinging from the grit that cold, dry puffs of wind were kicking up. At least his hangover was on the wane; all he felt now were a certain wateriness in the lower belly, and a feculence of mucus rammed up both nostrils, not unlike two small coral reefs.

As he paced he kept looking at his watch, feeling time course away from him, while he remained imprisoned in a permanent, embarrassed agony of the present. It was the window of Smith's that snapped him out of it, provided the visual salts. A rack of copies of the

Radio Times

was positioned so as to grab the attention of passers-by. It grabbed Richard all right, grabbed him like a street fighter grabbing a collar, thrusting a belligerent face into a cowering one. But it wasn't

a

face, it was faces. Bell's faces, serried ranks of Bells,

a tintinnabulation of them resounding in Richard's head. Below each smiling visage was a version of his ever mutable slogan: ‘Can You Ring Me?’

Richard resolved compromise. He got back on the tube and headed into town. Getting out at Tottenham Court Road he walked along to a menswear store and bought a pair of black chinos, a black blazer, a black pullover shirt, clean underwear and socks. He couldn't afford all of it really, but also couldn't stand not to look presentable, Ursula-worthy.

Richard slid into the Sealink at five to seven, and ducked along the corridor to the gents’. Here he shaved with nose-hair-paring exactitude. He also crouched in one of the stalls, to swab the grooves of his body with wads of moistened toilet paper, before scrabbling at the cellophane packaging and wrapping himself in his new finery. Five more minutes in front of the mirror – ignoring the comments of Sealink regulars as they filed past him to snort, scratch and sniff – and Richard was as ready as he'd ever be. He advanced along the corridor, towards the bar, at a steady trot. A Norman knight at Agincourt.

The first arrow came barrelling down vertically on him from the barman, Julius. Richard entered the bar,

sidled up to the bar, put his elbow on the bar, and undertook the subtle business of gaining the barman's attention. This took about fifteen minutes. Finally the orange divot was in front of Richard and he essayed the following casual enquiry: ‘Julius – seen Ursula?’

‘No,’ came the reply, the ‘N’ riving him from occiput to nape, the ‘o’ set alight and dropping neatly around his neck.

Not here?

It was now ten past seven – she

had

to be here. Was she toying with him?

‘I'll have – ‘ but the orange divot was gone, to the other end of the bar, to serve an actor whose most impressive credit to date was the voiceover for a Pepto-Bismol advert.

Richard ranged the Sealink Club with the loping, multijointed gait of a maddened polar bear. He charged upstairs, fell downstairs, looked in the brasserie-style cafeteria, the cafeteria-style brasserie, the table-football room; he even called her name several times outside the ladies’, softly, every bit of him agitated but pitching it low, in three quavering syllables, ‘Uuuur-suuuu-laaa . . .’, until two hack-harridans emerged, knock-kneed with merriment – charged on his account.

Then he was back in the bar for a while, clenching and

unclenching his hands around fictive balls of hard, realistically rubber anxiety. Richard didn't want Kelburn, Reiser, Slatter and all the others to turn up before her – it was unthinkable. He'd be sucked straight back down that plughole of loathsomeness, which connected directly to the sewer of the previous night. He must at least speak with Ursula alone before this happened. He had to capitalise on the Post-it note.

Richard thought of the private room he and Reiser had been in the evening before. Could she be up there? One of the chambermaids who serviced the room had also been serviced by Bell. Richard found it hard to credit, but the experience indebted her to him. She made sure that a copy of the key was available for Bell, or any of his cronies, when they required sequestration from the rest of the club.

If Ursula was up there, what could she possibly be doing? The long day of speculation, insecurity and hair-trigger lust was beginning to tell on Richard. He contemplated lurid images of Ursula going down – on Reiser! On Slatter! On Kelburn! On still weasellier, greasier members of the clique. As the phantom figures mounted one another in his mind, Richard mounted the stairs. By the time he reached the fifth floor his heart

was pounding, his visual field expanded and contracted, a squeezebox of perception. Without pausing to summon himself he straight-palmed the door open.

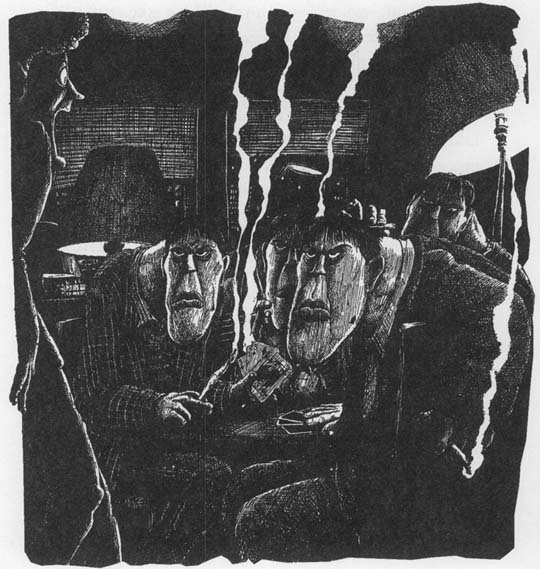

It crashed back on its hinges to reveal that a small gate-leg table had been set up in the very centre of the room; around this four figures were grouped playing cards. From their clothing and the set of their bodies, Richard recognised the clique members Reiser, Slatter, Kelburn and Mearns – the greenmailer. But when their faces turned to the source of the interruption, Richard saw four sets of near-identical features. Each of them had the same thick-set neck, the same jutting jaw, the same high, white forehead, the same red lips and broad-bridged nose. It was a group of Bells – a belfry. Four sets of black eyes examined Richard for a long, long fraction of a second. They bored into him, as if he were a diseased liver on which they were keen to do a biopsy.

The sight of the belfry was so incomprehensible, so weird, that Richard fell back against the wall of the corridor, mouthing – rather than saying – ‘What the fu – ‘. He rubbed his eyes; he felt dizzy, nauseous, as if about to faint. He sank to his knees.

Then a firm hand grasped Richard's shoulder, and a

firm – yet soft – voice clasped his ear: ‘What's the matter, Richard?’ Richard shook his head, his vision cleared, he looked up into the black eyes, began to recoil – but this time it was the real Bell, the authentic Bell. ‘Come on, come in here.’ Bell lifted Richard up under the arms. Lifted him as easily as another man might pick up a free newspaper, as a prelude to throwing it in a dustbin. It was the first time the big man had touched Richard, and he found it disconcertingly thrilling – Bell was so strong, so adamant.

Bell dropped Richard in an armchair inside the room. The others had left off their card game. They were still twisted round in their seats, but they no longer had the appearance of Bell clones. They had their own faces back, their own, leering faces. Todd Reiser stood up, brushing the outsize ash-fragments of a joint from his little lap, and said, ‘All right now, young Richard? You were out for the count there for a moment . . .’

‘I'm – I'm fine, really. Fine. Just took the stairs too fast.’

‘Not feeling the pace, are we young Richard? Too many late nights, too much

fun?’

This was sneered. Reiser couldn't

do

concern.

‘N-no, really. It was the stairs, and then seeing you all . . . You all looked like . . .’

‘What?’ This was from Slatter, who was openly worrying a cuticle with yellow teeth. ‘What did we look like?’

‘Y-you all looked like . . .’ – Richard indicated the big man, who was now standing over by the window – ‘. . . like Bell.’

The room exploded in laughter, different varieties of sarcastic cackling, all the way from Slatter's wheezing, nominal ‘Hugh-hugh-hugh-’ to Reiser's exploitative, pronominal ‘Her-her-her-her-'; even Bell heaved a little. Richard was still too dazed to be shamed by this; he was running over the past minute or so in his mind, again and again. Had there really been four Bells in the room? Or had it just appeared that way? After all, Bell's ubiquity was undeniable; and if Richard was going to have a hallucination, it was fairly likely to incorporate the man whose actions, whose thoughts, obsessed him. If it hadn't been Bell, who else but –

‘Ursula!’ cried Mearns, the greenmailer. ‘How lovely to see you; you look quite, quite marvellous.’ He rose and went to meet her. Richard unstuck his head from his hands and blinked. She was standing in the doorway,

bracing herself with both hands held above her head. She had one thigh raised up and half-crossed over the top of the other. She was wearing some sort of golden, spangled top, the spangles scattered over a fine mesh that exposed as much as it concealed her magnificent

embonpoint.

And Ursula wasn't just wearing a short skirt, she was wearing a pelmet – a little flange of thick, green, brocaded material that hung down, barely covering her lower abdomen. To either side of this lappet, flaring curtains of material descended. If Ursula had been straight-legged, ordinarily disposed, this would have presented a decorous enough picture. However, given the attitude she had struck, the longer drapes of cloth fell away, making an arch that framed the very juncture of her thighs. Richard let fly with a deep, glottal groan.

This was ignored by the others, who all rose and went over to Ursula. One by one they all kissed the air some inches in front of her cheek, as exemplary an acknowledgement as possible of the fact that they would rather be some inches

inside

her body.