The Sunlight Dialogues (109 page)

He bit his lip, pausing a moment, and hungered for a cigar. Would they mind? he wondered. Would they even really notice if he took out a cigar and lit it? When he looked at them this time they seemed to him farther away, as if the whole room were receding—not swiftly, but slowly, definitely, determinedly receding. He got out the cigar and, after a moment, lit it.

“Well things are getting better, some ways, we know. There are supermarkets in India now, or so I read—‘super bazaars,’ they call them. You can buy such things as pressure cookers, egg slicers, meat grinders, and packaged varieties of food—all made right in India. Everything’s got a price tag, which is very important

as nobody knows better than the farmer

(There! he’d got

that

in!), and it’s all self-service which, as we all know, is the best way to do it, and the truly American way. But then on the other hand there are signs that things are getting worse. A thousand people a day dying of famine right there in India for instance. Or for instance take the problem of advertising. It’s getting so advertising’s so plain outright obscene you wonder if it’s bad for children’s minds, such as, ‘Does she or doesn’t she?’ and ‘Had any lately?’ and that shaving ad for Noxema where the lady is saying ‘Take it off, take it all off.’ And there’s the problem all over the world of juvenile delinquency, for instance, even in Russia. I forget the statistics on it, but they’re something staggering, believe me. And yet it seems like the worse things get the harder it is for us to arrest a criminal. In San Francisco, California, according to what I read, every time they arrest a person they have to hand him a card that tells him what his rights are. If that makes you nervous, well I can’t say I’m surprised. It does me too.”

He paused again. It was none of it exactly what he’d meant to say. It had nothing to do with his feeling about the man who’d been killed, and nothing to do with his own feelings either, for that matter, his own feelings about being here, talking with friends—He felt his mind fumbling, lost.

“There’s been a lot of talk,” he said. “About me, about the Mayor, about the people over there in the fire department …” He felt himself getting angry, and he wasn’t sure why. “We do the best we can. You know that. And I want to say I know

you

do the best you can too, or anyway some of you do, and I have the utmost confidence that the people of Batavia will not go off half-cocked about a lot of false rumors.” He wished they would turn the lights up more. He could hardly make out the people at the table beside him. “There may be those—” he said. He squinted. Someone was whispering. “There may be those who condemn what happened tonight with the Sunlight Man. I won’t hide it from you. I’ll tell you right out. He came barging in there to give himself up and the man at the desk got panicky and shot him, that’s all there was to it. A terrible mistake, plain murder, you may say. And it was. But let me tell you this: It ain’t easy, sitting in there listening to the radio crackle and knowing there’s crimes going on in this city and you can’t be everywhere at once. It ain’t easy to know they’re gunning for you—following you around, dogging your footsteps, ready to topple you the first time you go and put your foot down wrong. Think of it! You’re sitting at the desk, nothing happening, mind full of stories of the Sunlight Man-murdering, robbing, scaring people in their beds, so the rumors have it anyhow—and all of a sudden

WHOP!!”—

he banged the table—”he’s right there in front of you like magic! You

know

what you’d do. Don’t you

fool

yourself, mister. It’s the same all around us. The Negro problem! Or the China problem! Face the truth! Juvenile delinquents setting fire to your store, or dogs hunting children in the streets of the city, or somebody poisoning your calves with paint, or lightning striking, or the end of the world!”

whop!!

It filled him with exhilaration and he banged the table again and then again,

whop!!

WHOP!!!

Then he put his hands down, shaking all over, collecting his thoughts.

“We may be wrong about the whole thing,” he said. “The whole kaboodle. If we could look at ourselves from the eyes of history—” His voice trembled. He squinted, panicky, momentarily believing they had all disappeared and the hall was empty. But they were there, leaning on their knees, listening, eyes as bright as the eyes of birds of prey, far in the distance. He wiped the sweat from his forehead.

“We may be dead wrong about the whole kaboodle,” he said wearily. He thought of the Sunlight Man shot through the heart, how he’d said when the Universe told him to jump he would jump; and now—because Luke was his nephew, it came to him: Luke was his brother’s son, and he would be alive today if it weren’t for the anarchist Taggert Hodge—now, because Luke was his nephew and had died on account of him—he had jumped. “We may be wrong,” he said. “We have to stay awake, as best we can, and be ready to obey the laws as best as we’re able to see them. That’s it. That’s the whole thing.” His face strained, struggling to get it all clearer, if only to himself. He thought of Esther. “Now there’s a fine model for us all,” he said emphatically, pointing at the ceiling. They all looked up, and he was flustered. He should go home. Then they were watching him again, as wide-eyed and still as fish. “Blessed are the meek, by which I mean all of us, including the Sunlight Man,” he said. “God be kind to all Good Samaritans and also bad ones. For of such is the Kingdom of Heaven.”

Then, abruptly, Clumly sat down and scowled.

No one clapped, at first.

The silence grew and struggled with itself and then, finally, strained into sound, first a spatter and then a great rumbling of the room, and he could feel the floor shivering like the walls of a hive and it seemed as if the place was coming down rattling around his ears but then he knew he was wrong, it was bearing him up like music or like a storm of pigeons, lifting him up like some powerful, terrible wave of sound and things in their motions hurtling him up to where the light was brighter than sun-filled clouds, disanimated and holy. The Mayor was there at his side, surging upward, it seemed to Fred Clumly, and crying happily, “Bravo, Clumly!” and the Fire Chief said happily, “Powerful sermon! God forgive us!” And Clumly, in a last pitch of seasickness, caught him in his arms and said, “Correct!” and then, more wildly, shocked to wisdom, he cried,

“Correct!”

All this, though some may consider it strange, mere fiction, is the truth.

John Gardner (1933–1982) was a bestselling and award-winning novelist and essayist, and one of the twentieth century’s most controversial literary authors. Gardner produced more than thirty works of fiction and nonfiction, consisting of novels, children’s stories, literary criticism, and a book of poetry. His books, which include the celebrated novels

Grendel

,

The Sunlight Dialogues

, and

October Light

, are noted for their intellectual depth and penetrating insight into human nature.

Gardner was born in Batavia, New York. His father, a preacher and dairy farmer, and mother, an English teacher, both possessed a love of literature and often recited Shakespeare during his childhood. When he was eleven years old, Gardner was involved in a tractor accident that resulted in the death of his younger brother, Gilbert. He carried the guilt from this accident with him for the rest of his life, and would incorporate this theme into a number of his works, among them the short story “Redemption” (1977). After graduating from high school, Gardner earned his undergraduate degree from Washington University in St. Louis, and he married his first wife, Joan Louise Patterson, in 1953. He earned his Master’s and Ph.D. in English from the University of Iowa in 1958, after which he entered into a career in academia that would last for the remainder of his life, including a period at Chico State College, where he taught writing to a young Raymond Carver.

Following the births of his son, Joel, in 1959 and daughter, Lucy, in 1962, Gardner published his first novel,

The Resurrection

(1966), followed by

The Wreckage of Agathon

(1970). It wasn’t until the release of

Grendel

(1971), however, that Gardner’s work began attracting significant attention. Critical praise for

Grendel

was universal and the book won Gardner a devoted following. His reputation as a preeminent figure in modern American literature was cemented upon the release of his

New York Times

bestselling novel

The Sunlight Dialogues

(1972). Throughout the 1970s, Gardner completed about two books per year, including

October Light

(1976), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the controversial

On Moral Fiction

(1978), in which he argued that “true art is by its nature moral” and criticized such contemporaries as John Updike and John Barth. Backlash over

On Moral Fiction

continued for years after the book’s publication, though his subsequent books, including

Freddy’s Book

(1980) and

Mickelsson’s Ghosts

(1982), were largely praised by critics. He also wrote four successful children’s books, among them

Dragon

,

Dragon and Other Tales

(1975), which was named Outstanding Book of the Year by the

New York Times

.

In 1980, Gardner married his second wife, a former student of his named Liz Rosenberg. The couple divorced in 1982, and that same year he became engaged to Susan Thornton, another former student. One week before they were to be married, Gardner died in a motorcycle crash in Pennsylvania. He was forty-nine years old.

A two-year-old Gardner, shown here, in 1935. He went by the nickname “Buddy” throughout his childhood.

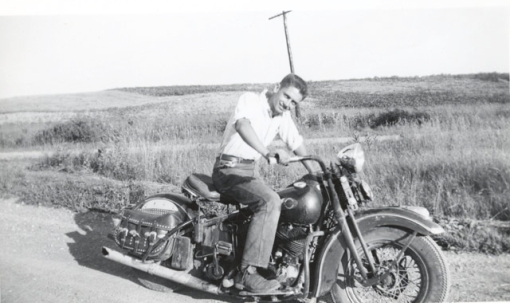

Gardner on a motorcycle in 1948, when he was about fifteen years old. He was a lifelong enthusiast of motorcycle and horseback riding, hobbies that resulted in multiple broken bones and other injuries throughout his life.

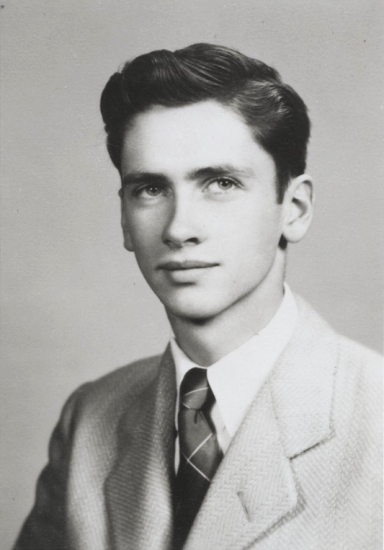

Gardner’s senior photo from Batavia High School, taken in 1950. Though he found most of his classes boring, he particularly enjoyed chemistry. One day in class, Gardner and some friends disbursed a malodorous concoction through the school’s ventilation system, causing the whole building to reek and classes to be dismissed early.