The Sugar King of Havana (4 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

A

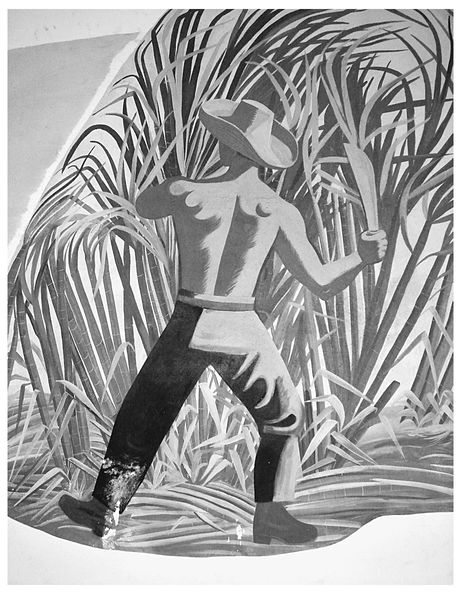

machetero

from a Galbán Lobo mural, Old Havana.

machetero

from a Galbán Lobo mural, Old Havana.

Lobo and his adviser León got out of the car and headed into the building. Lobo walked with a limp due to a murder attempt fourteen years before that had blown a four-inch chunk out of his skull after he had supposedly refused to pay $50,000 in protection money to a gang of Cuban mobsters. The machine-gun bullets had also shattered his right leg and left knee. One bullet had lodged near his spine.

Inside, the central bank was a mess. Guevara had only been central bank president for a few weeks. But the once-pristine financial building was dirty and disorganized, with papers all over the floor.

Guevara certainly made for an unlikely central banker. He loved telling the story of how he got the job. Supposedly, at a cabinet meeting to decide who should be the new bank governor, Fidel Castro had said that what he needed was a good “

economista.

” Guevara stuck up his hand, much to Castro’s surprise. “But Che, I didn’t know you were an economist!” “Oh, I thought you said you needed a good

comunista

,” Guevara replied. The response gives a good measure of his priorities. He casually signed the new Cuban banknotes “Che,” and only a few days before Lobo’s meeting had cut short an architect in the middle of a presentation of his plans for a new state-of-the-art central bank building. The foundations had already been laid at a site on the seaside Malecón, and because of the autumn storms, as the architect explained, the thirty-two-story American-style skyscraper needed hurricane-proof windows too. “Look,” Guevara said. “For the shit we’re going to be guarding here within a few years, it’s preferable that the wind takes the lot.”

economista.

” Guevara stuck up his hand, much to Castro’s surprise. “But Che, I didn’t know you were an economist!” “Oh, I thought you said you needed a good

comunista

,” Guevara replied. The response gives a good measure of his priorities. He casually signed the new Cuban banknotes “Che,” and only a few days before Lobo’s meeting had cut short an architect in the middle of a presentation of his plans for a new state-of-the-art central bank building. The foundations had already been laid at a site on the seaside Malecón, and because of the autumn storms, as the architect explained, the thirty-two-story American-style skyscraper needed hurricane-proof windows too. “Look,” Guevara said. “For the shit we’re going to be guarding here within a few years, it’s preferable that the wind takes the lot.”

None of this boded well for Lobo. But when he climbed the stairs, Guevara greeted him politely in the doorway of his office on the second floor. “Señor Lobo, it is good of you to come,” Guevara said. “Apologies that we bothered you at this late hour.” They shook hands, and Guevara invited Lobo into the room and to take a seat.

I read in Lobo’s diaries how he felt surprised by Guevara’s cordial, if formal, mood. He mentions this twice in his written recollection of the evening, having probably expected more brusque treatment. Lobo also stressed, again twice, that he and Guevara had never met before, although their paths had already crossed several times indirectly, and in ways that illustrate the intimacies and deeply personal social networks that still characterize Cuba.

Celia Sánchez, Fidel Castro’s confidante and secretary since the earliest days of the revolution, was the daughter of the dentist on one of Lobo’s eastern plantations, El Pilón. Several years before, Lobo had built what he called “a dovecot” on the estate where Sánchez, an eccentric woman in her thirties, could “sleep, write or dream,” as he put it. She was also a close friend of Lobo’s daughter María Luisa. Together, they had set up clinics and other help for indigent sugar workers at and around Lobo’s mill.

Guevara had also stumbled through one of Lobo’s eastern cane fields on December 5, 1956, shortly after landing in Cuba for the first time. It had been an inauspicious introduction to the island. The sea voyage that Guevara had made with Fidel Castro and eighty other rebels across the Gulf of Mexico had been an unmitigated disaster. It had taken seven days, instead of five. Then, weakened by seasickness, the rebel force had landed at the wrong spot on Cuba’s coast. Their navigator had fallen overboard just before landing, and the boat had run aground on a sandbar, turning their arrival in Cuba into more of a shipwreck than a landing. The expedition had then slogged through mangrove swamps, jettisoning most of its equipment, leaving the rebels with only rifles, cartridge belts, and a few wet rounds of ammunition. They had tried to satisfy their thirst and hunger by chewing on sugarcane in the fields of Lobo’s Niquero mill. Foolishly, they also left a careless telltale trail of bagasse, or cane peelings, all over the place. The next day they were ambushed by Batista’s forces. In the melee that followed, Guevara was hit by a ricochet bullet in the neck. Blood poured from his wound, and Guevara, who had trained as a doctor, believed himself mortally wounded and went into shock. “I lost hope for a couple of minutes,” he wrote in his field diary.

Of the eighty-two men who came ashore, only twenty-two ultimately regrouped in Cuba’s eastern mountain range, the Sierra Maestra, where they were helped by Celia Sánchez and a truck driver from one of Lobo’s plantations, Cresencio Pérez.

Now at the central bank, Lobo and Guevara faced each other for the first time. They could not have looked more different. Che, the guerrilla, the bearded thirty-two-year-old revolutionary, was dressed in green battle fatigues, a revolver slung across the glass desk. This was the man who would later explain to Cubans that the reason visiting Russians were so poorly dressed and often smelled of sweat was that deodorant and soap were superfluous in a genuine revolution.

By contrast, Julio Lobo, the arch-capitalist, was a dapper dresser who used Eau de Cologne Imperiale de Guerlain and hosted literary parties at his favorite sugar mill, Tinguaro, which he believed to be the “Cliveden of Cuba.” While Guevara was the face of Cuba’s “New Man,” Stakhanovite in his labor and fervent in his belief that individualism should disappear, Lobo was a friend of Hollywood stars such as Joan Fontaine, Esther Williams, and Maurice Chevalier, who often stayed on his estates.

Lobo and Guevara were opposites in so many ways, yet they had more in common than what might have at first been apparent. Both were lucid and deeply rational men. Guevara looked to the various intellectual constructs of international communism. Lobo hewed to the modernizing enlightenment ideals that had shaped the beliefs of some of his Cuban sugarcrat predecessors. Both were loners. Guevara’s terrible asthma attacks often kept him apart from others, while his mordant Argentine humor didn’t always gel with the more flippant Cubans. As for Lobo, he used to say that Napoleon was a lonely character, and so was he.

Both men were austere in their habits. Lobo might have lavished gifts on others, and decked out his house with original paintings by European masters like Sisley, Utrillo, Vlaminck, and Turner, but his personal life was almost spartan. His bedroom had once been a reconstruction of his bachelor quarters from student days, with a simple wooden bed, a side table, and a solitary chair—similar to the simple living arrangements of Guevara.

Both men were candid to the point of brutality. Both engendered fierce loyalty. Contrary to the usual stereotype of the heartless and absent sugarcrat, Lobo visited his plantations often and was well regarded by employees. After the revolution his workers even sent delegates to Havana to request that Lobo’s mills not be nationalized. Like Guevara, Lobo was scrupulously honest too. He claimed to have refused the secretaryship of the Cuban treasury under a former president on the grounds that the administration was too corrupt.

Indeed, that night in October 1960, Lobo believed that Guevara had ostensibly sent for him to talk about certain monies owed in connection with the construction of the Riviera and Capri hotels. But Guevara, with his usual frankness, explained to Lobo that he and his aides had examined Lobo’s accounts and found no irregularities. “Not a stain, or a blemish,” as he put it.

“What did you expect to find?” Lobo interjected.

“. . . and because of that,” Guevara continued, ignoring Lobo’s question, “we have left you to last.”

Lobo said nothing; he was used to playing the cipher and, facing Guevara, he put on his bravest face to hide the uneasier emotions that ran underneath. Some of these are revealed in a letter written the year before, when Lobo had quoted the eighteenth-century Irish writer Oliver Goldsmith: “Man wants but little here below, nor wants that little long.” Might Lobo, the billionaire who lacked for nothing, have had an early presentiment of his own fate? Perhaps. Lobo, who had suffered morbid thoughts lately, then mused that everyone would be so much better off if they could only remember the wisdom of Goldsmith’s words. Typically, Lobo then changed tack quickly, shrugging off any sense of fatalism, and asked rhetorically: “But what is the point of life if there is no desire to create, to build, to construct? Probably only fishing and hunting with a g-string, as our millennial ancestors used to do.” The letter closes suddenly on a firm note, Lobo apparently having made up his mind. “One of the most human of all desires is to perpetuate what you have created, and I think for the time being that is the business at hand.”

That was indeed the business at hand for Lobo that night at the Cuban central bank. When Guevara said that he had been saved until last, Lobo knew that his time had come, the moment when his bicycle might wobble, when the great machine of the empire that he commanded from the bridge of his ship might flounder, when it might sink.

GUEVARA FINISHED HIS PREAMBLE. He had led the talking for the past half hour, and had even complimented Lobo on his honesty, albeit in a backhanded way. Lobo sat in silence in an overstuffed chair, his adviser Enrique León beside him. A clock ticked on the mantelpiece; it was twelve thirty at night and, outside, most of the city was asleep. Lobo waited for Guevara to continue.

Sitting in that government room in downtown Havana, papers scattered around the floor, Lobo knew that to the revolutionary government his sugar mills were an emblem of two hundred years of subjugation, not only of slaves but of a whole country. That March, Guevara had called sugar “economic slavery.” Yet Lobo also knew that to unpick and roll back Cuba’s sugar history would take more than the bureaucratic stroke of a pen, or even a revolution. “

Sin azúcar no hay país

,” without sugar there is no country, is the famous, damning phrase that had continued to define the island—even more, perhaps, than Fidel Castro’s revolution would come to do.

Sin azúcar no hay país

,” without sugar there is no country, is the famous, damning phrase that had continued to define the island—even more, perhaps, than Fidel Castro’s revolution would come to do.

Cuba and sugar had been tied at the hip since the British had captured Havana in 1762 and thrown the island open to the slave trade. Sugar, the wealth it generated, and the slaves that its plantations required had set the course of the country’s economy, culture, and political life ever since. The slaves who worked in its sugar plantation economy had transformed Cuba from a mainly white and Spanish colony into the more variegated island it is today. It was the riches of sugar that alternately acted as an engine for, and then a brake on, Cuba’s independence movements of the nineteenth century. It had also shaped Cuba’s ambivalent relationship with the United States. Agustín Acosta had struck a deep chord with his anti-epic poem

La Zafra

, the harvest, published in 1926, in which wagons carrying sugar to U.S.-owned mills

La Zafra

, the harvest, published in 1926, in which wagons carrying sugar to U.S.-owned mills

. . . ford the streams . . . they cross the mountains

Carrying Cuba’s fate in sugarcane.

They go towards the nearby colossus of iron:

They trundle towards the North American mill,

And as though complaining on their approach,

Loaded, heavy and replete,

The old carts creak . . . creak.

Carrying Cuba’s fate in sugarcane.

They go towards the nearby colossus of iron:

They trundle towards the North American mill,

And as though complaining on their approach,

Loaded, heavy and replete,

The old carts creak . . . creak.

Acosta’s poem is an emotive portrait of resignation and woe, yet it is also a more complicated and richer picture than it first seems. Those “colossuses of iron” of which Acosta writes, magnificent monuments to capitalism, were not all foreign-owned. Sugar mills also defined Cuba’s own restless, entrepreneurial, and worldly planter class. In the eighteenth century, there were resourceful planters like the creole economist and anglophile Francisco Arango y Parreño, who traveled, cloaked and with a false mustache, to Liverpool in 1788 to spy on England’s latest technical developments such as the steam engine. Just as Arango and his patrician friends, often viewed as the fathers of the nation, looked to the world for technical and political inspiration, so too had Cuba looked to them as banners of modernity and sources of homegrown power in opposition to its then colonial master, Spain. In one typical incident in 1834, General Miguel Tacón, the survivor of various wars of Latin American independence and one of Cuba’s most reactionary governors, was outraged that railways should come to Cuba before Spain, and freely expressed his contempt for such “Anglo-Saxon ironmongery.”

Cuba’s liberal creole tradition continued through the nineteenth century when some planters, including some of my ancestors, fought in the wars of independence against Spain. Many years later, Fidel Castro cast his revolution against the Yankee imperialists as a continuation of their heroic struggle. Finally, in the twentieth century, there was Julio Lobo, the embodiment of Cuba’s erudite and cosmopolitan sugarcrat elite, indeed its apogee, a man who had used his sugar wealth to wrest the industry out of foreign hands, who knew better than any the byways of the international sugar trade, who had even supported Cuba’s homegrown creole rebels just as some of his predecessors had done. To separate sugar from Cuba, Lobo knew, one might as well chop away the arterial system of a body and imagine that it could somehow survive. So despite Guevara’s plans for Soviet-style industrialization and self-sufficiency, Cuba’s revolutionary government needed sugar. Because of that, it also needed men like Lobo.

Other books

Sweet Madness: A Veiled Seduction Novel by Snow, Heather

Thieves Dozen by Donald E. Westlake

Jenny's War by Margaret Dickinson

Gotham: After Dark - The King Slayer by Dustin Brubaker

A Pocket Full of Murder by R. J. Anderson

Gaffers by Trevor Keane

Battle Angel by Scott Speer

Bad Traffic by Simon Lewis

A Birthright of Blood (The Dragon War, Book 2) by Arenson, Daniel

This Is Gonna Hurt by Tito Ortiz