The Storyteller (6 page)

Authors: Walter Benjamin

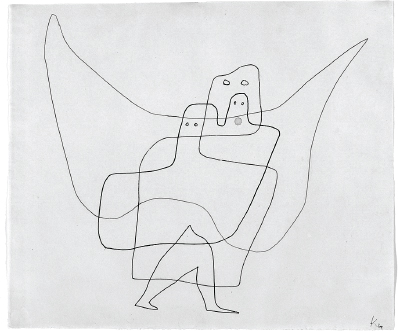

Dream I

In Angel's Care (In Engelshut)

, 1931.

O

â¦s showed me their house in the Dutch East Indies. The room in which I found myself was panelled with dark wood and aroused the impression of prosperity. But that is really nothing, said my guides. What I really must admire was the view over the open sea that was nearby, and so I climbed the stairs. Once at the top, I stood in front of a window. I looked down. There in front of my eyes lay that warm, panelled, and snug room, which I had, only a moment ago, left.

â

Translated by Sam Dolbear and Esther Leslie

.

Written 1933;

Gesammelte Schriften IV

, 429â30.

Dream II

In Angel's Care (In Engelshut)

, 1931.

B

erlin; I sat in a cab in the company of some highly ambiguous girls. Suddenly the sky darkened. âSodom', said a woman of mature years in a bonnet who suddenly also appeared in the carriage. In this way we arrived at the purlieus of the train station, where the platforms stretched outwards. It was called something like Oranienburg Station. Here court proceedings were taking place, in which both parties sat opposite each other on two street corners, on the bare pavement. Although the proceedings involved things including property rights, the opposite party was my brother, but my wife was absent. I referred to the overgrown, bleached moon, which bulged low in the sky, as if a symbol of justice. Then I was on a small expedition, which moved downwards on a ramp such as exists in a freight yard (I was in the purlieus of the train station and stayed there). It seemed like the Sternbergian circle â Döblin

was, in any case, among them. They stopped in front of a very narrow rivulet. The rivulet flowed between two bands of convex porcelain platters, which floated more than they were fixed, and gave way underfoot like buoys. As for the second one, on the other side, I was not sure whether it was porcelain. More likely glass. Either way, they were totally covered in flowers, which emerged like bulbs from glass containers, only from spherical, colourful ones, and they gently struck against one another in the water, again like buoys. I stepped into the flowerbed on the other side for a moment. At the same moment, I heard the elucidations of a small sub-officer who led us. In this gutter, as his remarks conveyed, suicidal people kill themselves, those poor fellows, who have nothing more than a flower, which they hold between their teeth. Now this light fell on the flowers. Like the Acheron, one might think to oneself; but this was not in the dream. I was told in which place I should put my foot on the first platter when returning. At this spot, the porcelain was white and serrated. In conversation we walked back from the depth of the freight yard. I mentioned it to Döblin, the strange texture of the tiles, which we still had underfoot, and that they might be used in a film. But he didn't want to speak so publicly of such projects. Then at once, a lad in rags and tatters came towards us on his way down there. It seemed the others calmly let him pass, apparently only I searched feverishly in my pockets: I wanted to find a five-mark piece. It didn't appear. I slipped him a somewhat smaller coin when he crossed my path â for he did not stop on his way â and I awoke.

â

Translated by Sam Dolbear and Esther Leslie

.

Written 1933;

Gesammelte Schriften IV

, 430â1.

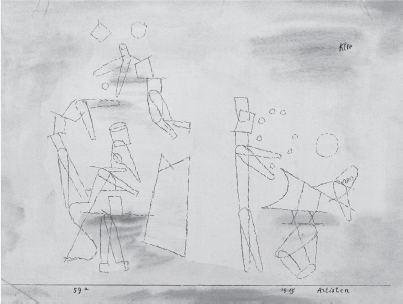

Once Again

Acrobats (Artisten)

, 1915.

I

n the dream, I was in the educational house in Haubinda, where I grew up. The school house lay behind me and I went into the forest, which was deserted, towards Streufdorf. It was now no longer the spot where the forest opens out onto the plain, where the landscape â village and Straufhain's peak â emerged. Rather, once I had climbed the low mountain at a gentle incline, it suddenly dropped almost vertically on the other side; and from the elevation, which lessened as I descended, I saw the landscape through an oval opening

amid the treetops, like a black ebony photo frame. In no way did it resemble the one I expected. On a large blue stream lay Schleusingen, which in fact lies far elsewhere, and I didn't know: is it Schleusingen or Gleicherwiesen? Everything was as if bathed in humid colours and yet a heavy and wet black prevailed, as if the image were the field which only just now, in the dream, had once again been painfully ploughed, and in which the seeds of my later life had then been sown.

â

Translated by Sam Dolbear and Esther Leslie

.

Written c. 1933;

Gesammelte Schriften IV

, 435.

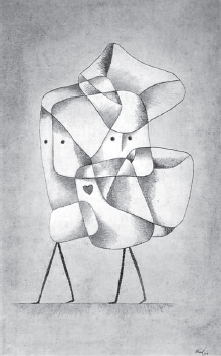

Letter to Toet Blaupot ten Cate

Siblings (Geschwister)

, 1930.

â¦Y

ou see, even my summer represented a major contrast to the last. Back then, I could â as an expression of a totally fulfilled experience â never get up too early. Now I sleep, not only longer, but the dreams persist, often recurring, into the day. In the last few days it was of picturesque and beautiful architecture: I saw B and Weigel

1

in the shape of two

towers or gate-like structures swaying through the city. The flood of this sleep, which forcefully broke against the day, is moved by the power of your image, like the lake is by the pull of the moon. I miss your presence more than I can say â and, what's more â more than I could believe.

â

Translated by Sam Dolbear and Esther Leslie

.

Written summer 1934 while with Brecht in Denmark;

Gesammelte Schriften VI

, 812.

A Christmas Song

The Lovers (Der Verliebte)

, 1923.

O

f all those songs, the one I loved the most was a Christmas song that filled me, as only music can, with solace for a sorrow not yet experienced but only sensed now for the first time.

I lay and slept and dreamed

a very beautiful dream

There stood on a table in front of me

the most beautiful Christmas tree.

But it was not only the magic of the melody which made this song tug my heart strings. For me the dreamer did not appear opposite the tree, his dream face awake, upright, rather in the song the sleeper remained and his dream stepped close to him, just as in images by primitive painters the Madonna stands by the bed of an ill person or a sleeper, to whom she has appeared, so âthe table before me' stood next to this bed. And the singing had so often brushed over that threshold between dream and waking that it was blurred and smoothed over.

â

Translated by Sam Dolbear and Esther Leslie

.

Written c. 1933â4; unpublished in Benjamin's lifetime and omitted from the

Gesammelte Schriften

. Taken from

Träume

, 26.

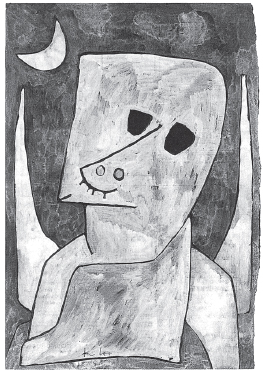

The Moon

Angel Contender (Engel Anwärter)

, 1939.

I

n a wide surge, which seemed to befit primeval times, the land swelled in front of this window. And the crest of the surge lifted this knight upwards in front of the woman as once the Sirens may have appeared on crests of waves before Odysseus. Such a sea was surely strange to the Greeks. But the earth, which

lifted up the knight in front of the window, was perhaps from the same substance as the woman, who, alongside the sleeping man, now corpselike, had become absorbed in this night by the distant, indistinct form. But was that the earth, whose satellite was the moon laying in this gleam? Had not its whole disc rather transposed the order of nature, so that the earth had become nothing more than a satellite of the moon, its nearby earth, on which now for its part was transposed the order of the day; the wife had become ruler, the mountains sea, sleep death?

Albert Welti,

Mondnacht

, 1917

A

nd again the rays of the moon shone like a magician's wand that reverses the order of nature. The echo, in particular, which now reached me, the more attentively that I listened out for it on the inside, became all the more a noise long-ago heard. The erstwhile seemed to already occupy all the sites of this nearby earth, and so it came that I eventually could approach

my bed, when I was just about to step into it, only with the concerned worry that I would have liked to have seen myself lying in it. My worries only completely faded away when I felt the mattress on my back.

M

y first walk was to the window. Through the cracks between the slats of the window blinds, I beheld the houses in the backyard. Sometimes my gaze also penetrated higher up. And then it transpired that, in the sky, the moon, with its light separate from the background of the starry heavens, stood in my field of vision. Never for a long period of time, for it always seemed advisable for me to turn myself away again quickly.

S

lowly the moonlight moved further along; sometimes it had already left my room before I fell asleep again. Then there was a question that arose inside me in the dark; I believe today, it was the other, unilluminated side of the fear that had gripped me in the moonlight. The question, though, was: why then is there something in the world, why does the world exist? Ever again with renewed astonishment I noticed that nothing could force me to think the world. It could have been missing. The non-existent was not one jot more hostile or stranger to me than existence. The beam of the moon could alienate its most familiar details from me.

T

hus I was the prisoner of the nights of the full moon, which threw the slats of my venetian blinds over my bed

cover. Once, however, the moon reappeared to me on the front side of the house. Childhood already lay long behind me, since finally we measured ourselves â like to like. Then finally it came to the great encounter.

Once, however, the moon reappeared to me on the front side of the house. Childhood already lay long behind me. But only then, never before and never after, the image of what is mine stepped clearly in front of me, at the same time as the moon. And I saw myself in this dream in their midst. Only my sister was missing. âWhere is Dora?' I heard my mother say. For the moon, once full in the sky, had suddenly grown bigger, coming closer and closer, it tore the earth apart. The railings of the iron balcony, upon which everyone had been sitting, went to pieces, and the bodies that had sat on it quickly dispersed into their cell particles.

When I awoke at night in the dark, the world was nothing more than a single mute question. It might be that this question, though I didn't know it at the time, sat in the pleats of the plush curtains which hung from my door to keep out the noise. It might also be that a reflection was its kernel, which sometimes sat in the brass knobs which crowned the foot of my bed. Maybe it was just the residue of a dream that had solidified upon awakening.

â

Translated by Sam Dolbear and Esther Leslie

.

Written c. 1933â4, concurrent with the writing of the moon sections in

Berlin Childhood

. Unpublished in Benjamin's lifetime and omitted from the

Gesammelte Schriften;

taken from

Träume

, 29â32.