The Storyteller (4 page)

Authors: Walter Benjamin

In a Big Old City

Novella Fragment

Two Facades (Dwie fasady)

, 1911.

T

here once lived a merchant in a big, old city. His house stood in one of the very oldest parts of town, on a narrow, dirty little alley. And on this alley â where all the houses were so old that they could no longer stand alone and had to lean against each other â the merchant's house was the oldest. But it was also the biggest. With its mighty, arched doorway and tall, curved windows made up of half-blind bullseye panes, and with the steep roof on which a number of narrow little skylights had been fitted, it looked quite strange â the house of the merchant, the last house on Mariengasse. This was a pious town and many of the houses had beautiful carvings of the holy virgin or some other saint above their doorways or

under their roofs. On Mariengasse, too, every house had its saint â only the merchant's house stood bare and grey without any adornments. Nobody lived in the big house except for the merchant and a small eight-year-old girl. The girl was not his daughter, but she lived with him; he brought her up and the child helped with the housekeeping. But how she came to live in the merchant's house, nobody really knew. The merchant was not some ordinary grocer from whom the people bought clothes or spices â no! Nor did he keep company with the poor, common residents of his street. Day in and day out, he sat in his large study with the tall cabinets and long shelves and did his accounts and calculations. For his trade extended far across the seas to far-flung, distant lands. At intervals â perhaps once or twice per year â he had to leave his house for an extended period, when his business affairs summoned him far away. At these times, the girl stayed home by herself and took care of the household. One day the merchant-lord stood, once again, before the girl to tell her that he was leaving home for some time. âI don't know when I will return,' he said. âTake care of the house as you have before â

but

', he interrupted himself, âI see you are old enough now; during my absence you can do as you please in the house. Here, take the keys.' The girl, who up until this point had stood silently in front of him, gazing wide-eyed at the strange, colourful flowers that were embroidered onto the lord-merchant's clothes, looked up and took the keys. Suddenly the merchant-lord looked at her with intent. Then he spoke in a stern tone of voice: âYou know very well that you may use the keys only for the rooms in which you see to the household chores. Never let yourself be tempted to ascend to the upper floor. Do you understand?' Timidly the girl assented. Then the merchant bowed down, kissed her, looked at her once more with a penetrating gaze, went down the stairs and left

the house. The front door slammed shut behind him with a bang. The girl was still standing by the stairs in a daze, gazing at the large bundle of ancient keys that she held in her hand.

â

Translated by Sebastian Truskolaski

.

Fragment written c. 1906â12; unpublished in Benjamin's lifetime.

Gesammelte Schriften VII

, 635â6.

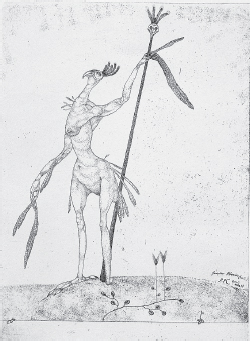

The Hypochondriac in the Landscape

Aged Phoenix (Invention 9) (Greiser Phönix [Invention 9])

, 1905.

ONLY FOR GROWNâUPS. NERVOUS TYPES â BEWARE!

A

bove the landscape hung such storm clouds as cause that specific fear of storms among young people known to physicians under a Latin name. It was a gently apprehensive mountain scenery. The path was steep and tiresome; the air was very hot and high temperatures prevailed. A mature man

â greyed by the passing of the years â and an adolescent moved as inaudible points through the silence. They carried an empty stretcher. From time to time the gaze of the younger man fell upon the stretcher and his eyes would fill with tears. It was not long before a doleful song streamed forth from his mouth, reverberating from the mountain with a thousand sobs. âRed of the morning, red of the morning lights the path to an early death.'

1

In the distance, bloody bolts of lightning tinged the sky. Suddenly the singing broke off and was followed by a faint groan. âPermit me for a moment', the young man said to the elder one. He rested the stretcher on the ground, sat down, closed his eyes and folded his hands.

At the peak of the landscape we find him again. A ruin stood there, overgrown by the green of nature. Storms and tempests roared more fiercely here than elsewhere. The place was created for the indulgence of every conceivable suffering ⦠Special weight was placed on melancholy, which took place between seven and eight o'clock each evening. A valley located in the shadow of the sinking sun turned out to be suitable. Moreover, a box of eyeglasses with black and dark-brown lenses was on hand, which could enhance the melancholia to a state of horror and raise the evening temperature from 37º to a feverish 40º. When the moon was full, 40º was the minimum temperature and a flag was raised to signal mortal danger.

The beautiful summer nights were used for sleeplessness. Nevertheless, the patients were awoken as early as five a.m. for their morning diagnosis. Monday and Friday mornings were devoted to testing for anxiety; Sundays were for nightly indigestion. Thereafter ensued six hours of psychoanalysis. Subsequently hydrotherapy, which was administered

telepathically due to the water, which tended to be wet and cold throughout most of the year. There followed a break at noon. It was dedicated to telephone consultations with European luminaries and to the theoretical exploration of diseases that have hitherto remained untargeted.

The meals are served in a chemically cleansed

Bazillopher

,

2

surrounded by ether and camphor fumes. The physicians oversee the procedure with a loaded rifle in order to slay any attacking germs. After being checked for various pathogens, the germs are doused with hot water, anatomically dissected, and killed. They then either appear on the supper table or in the exhibition rooms of the library, which contains the directory, description, danger and cure for all the diseases weathered by the patients to date.

For the twenty-fifth anniversary of each disease, a splendid monograph with cinematographic images is published. The library is open to patients between four and five every day and serves, above all, to incite new illnesses.

After dinner, physicians and patients organise germ hunts in the park. Oftentimes it happens that a patient is accidentally shot. In such cases a simple bed of moss and forest herbs is prepared as the patient sinks to the ground. Bandages lie ready in the tree hollows.

Everything has been provided for. Should the physician fall ill, an automatic operating room is provided, whose automated apparatuses perform all procedures upon the insertion of three to twenty pennies. At three pennies, the cheapest operation entails the chemical cleaning of the nose; for twenty pennies one can get treatments with life-threatening consequences.

One evening, a serious tête-à -tête took place. The following morning, the physician disappeared on a clinical study tour to explore the latest diseases.

â

Translated by Sebastian Truskolaski

.

Fragment written c. 1906â12; unpublished in Benjamin's lifetime.

Gesammelte Schriften VII

, 641â2.

The Morning of the Empress

The Witch with the Comb (Die Hexe mit dem Kamm)

, 1922.

H

ealthy people must turn to the books of poets in order to feel life in all the deep and undivided sovereignty that cannot be grasped intentionally, to feel it as it was felt by that ailing Empress of Mexico on the third day of spring in the year 18â. She had been brought to this palace such a long time ago that no one could keep track any longer. Who even thought that she was ill? None of her maids and servants â all of whom led boring lives inside this palace, only rarely tending to excess â believed it. A person had arrived whose beautiful, ageing body required all the care that servants could offer. She was loved by all for her splendour. The farmers from the environs of Palace

Drux told tales of this Empress who was foreign to the land, who was only supposed to die in that broad palace which towered above the plains of Holland.

But the Empress did not think of death, nor did she feel the life that stirred around her; accordingly she could be called disturbed of mind. Each evening when the sun went down, she pursued anew the question that haunted her like one of the broad paths that transforms in the twilight. This question was secret, and although the Empress had disclosed it to people she interacted with, the only answers she received were evasive, uncomprehending excuses â almost enough to infuriate â so that the Empress descended further and further down the ranks with this question: from the lady's companion to the chamber maid, from the maid to the equerry, from the equerry to the cook, and â finally â to the children. And, indeed, the children seemed to understand her question; but she understood the language of the children as little as that of thunder, although she had often begged this of God while kneeling on a prayer stool by the window. A vault lay in the basement of the palace, dark and filled with bottles of wine â there the Empress had struggled most deeply with the question. Hunched over, her tall figure under the low ceiling, she had fashioned a set of scales out of yarn and little tin bowls. She deemed these scales to be fine enough to examine the weight of the world. And this was her question.

â

Translated by Sebastian Truskolaski

.

Fragment written c. 1906â12; unpublished in Benjamin's lifetime.

Gesammelte Schriften VII

, 642â3.

The Pan of the Evening

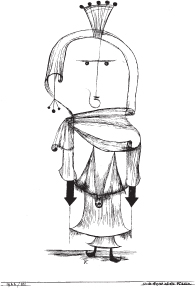

Little Jester in a Trance (Kleiner narr in trance)

, 1929

T

he evening had woven a shining pale yellow ribbon of magic over the snowy mountains and low wooded hilltops. And the snow on the peaks shone pale yellow. The forest, however, already lay in darkness. The glowing of the peaks awoke a man who sat on a bench in the forest. He looked up and relished the strange light from the peaks, looking into it until he had only a radiant flickering in his eyes; he thought

nothing more and only saw. Then he turned to the bench and took the walking-stick that leaned there. He said to himself, reluctantly, that he had to return to the hotel for dinner. And he trod slowly on the broad path leading down to the valley, watching his step because it was dusk and there were roots protruding from the ground. He did not know why he walked so slowly. âYou look ridiculous and pathetic stalking along on this broad path.' He heard these words clearly and with some indignation. He stopped defiantly and looked up at the snowy mountain tops. Now they too were dark. As he observed this, he clearly heard a voice inside him, a completely different one, which said âalone with me'. For this was its greeting to the darkness. Hereupon he lowered his head and trod onwards against his will. He felt as though he was about to hear another voice which was mute and grappled for speech. But that was despicable ⦠The valley was in sight ⦠The lights from the hotel were surging up. As he peered into the grey depths below, he fancied he saw a workshop down there. He felt from a pressure on his own body how giant hands were forming masses of fog, how a tower, a cathedral of twilight arose. âThe cathedral â you yourself are within it,' he heard a voice say. And he looked around as he walked on. But what he saw seemed to him so marvellous, so stupendous ⦠yes (quietly he felt it: so terrible) that he came to a stop. He saw how the fog hung between the trees, he heard the slow flight of a bird. Only the nearest trees still stood there. Where he had just been walking, something else had begun to spread, something grey. It covered up his steps as though they had never been taken. He realised as he walked here that something else walked through the forest too; a spell presided over things that made the old disappear, making new spaces and unknown sounds out of the familiar. More clearly than before the voice recited a rhyme from a wordless song: âdream and tree'.

As he heard this, so loud and sudden, he came to his senses. His eyes focussed; yes, he wanted to see in focus: âreasonable', warned the voice. He fixed his gaze on the path and, to the extent that it was possible, he distinguished. Over there a footprint, a root, moss, a tuft of grass, and at the edge of the path a large rock. But a new horror gripped him â as clearly as he saw, it was not as it usually was. And the more he mustered all of his strength to see, the more alien everything became. The rock over by the path grew larger â it appeared to speak. All relations were transformed. Everything particular became landscape, a spread-out image. Desperation seized him; to flee from all of this, to gain clarity in the horror. He took a deep breath and looked to the sky with resolve and composure. How strangely cold the air was, how bright and near the stars.

Did somebody scream? âThe forest', a voice rang loudly in his ears. He saw the forest ⦠He ran in, jostling against the tree trunks â only further, deeper through the fog, where he had to be ⦠where there was somebody who made everything different, who created the dreadful evening in the forest. A tree stump threw him to the ground.

There he lay and wept with fear, like a child who feels a strange man approaching in a dream.

After a while he grew silent â the moon came and the brightness dissolved the dark tree trunks into the grey mist. Then he recovered and went home.

â

Translated by Sebastian Truskolaski

.

Fragment written c. 1911; unpublished in Benjamin's lifetime.

Gesammelte Schriften VII

, 639â41; also translated in

Early Writings (1910â1917)

, 46â8.