The Storyteller (12 page)

Authors: Walter Benjamin

Tales Out of Loneliness

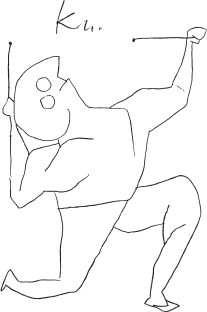

Knauer Drummed (Knauer Paukt)

, 1940.

I

had lived for a few months in an eyrie on Spanish soil. I often resolved to wander at some point in the vicinity, which was edged by a wreath of severe ridges and dark pine woods. In between lay hidden villages; most were named after saints, who might well have been able to occupy this

paradisiacal region. But it was summer; the heat allowed me, from one day to the next, to defer even the most cherished promenade to the Windmill Hill, which I could see from my window. And so I stuck to the usual meander through the narrow, shady alleyways, in whose networks one was never able to find the same crossing-points twice. One afternoon in this labyrinth I stumbled across a junk shop, in which picture postcards could be bought. In any case some were displayed in the window, and among them was a photo of a town wall, as has been preserved in this corner of the world. I had never seen one like this before, though. The photograph had captured its whole magic: the wall swung through the landscape like a voice, like a hymn through the centuries of its duration. I promised myself not to buy this card until I had seen the wall that it depicted with my own eyes. I told no one of my resolution, and I could refrain from doing with greater reason, for the card led me with its caption, âS. Vinez'. For sure I did not know of a Saint Vinez. But did I know more of Saint Fabiano, a holy Roman or Symphorio, after whom other market towns in the vicinity were named? That my guide book did not include the name did not necessarily mean much. Farmers had occupied the region, and seafarers had made their markings on it, and yet both had different names for the same places. And so I set about consulting old maps, and when that did not advance my quest at all, I got hold of a navigation map. Soon this research began to fascinate me, and it would have been a blot on my reputation to seek help or advice from a third party at such an advanced stage in the matter. I had just spent another hour poring over my maps when an acquaintance, a local, invited me for an evening walk. He wanted to take me in front of the town onto the mound, from where the windmills that had long been still had so often greeted me over the pine tops. Once we

managed to reach the top it began to grow dark, and we halted to await the moon, upon whose first beam we set about on our way home. We stepped out of a little pine wood. There in the moonlight, near and unmistakable, stood the wall, whose image had accompanied me for days, and within its protection, the town to which we were returning home. I did not say a word, but soon parted from my friend. The next afternoon, I stumbled suddenly across the junk shop. The picture postcards were still hanging in the window. But above the door I read on a sign, which I had missed before, âSebastiano Vinez', painted in red letters. The painter had added a sugar cone and some bread.

O

n a walk, in the company of a married couple who were friends of mine, I came close to the house I was occupying on the island. I felt like lighting my pipe. I reached for it and, as I didn't find it in its usual place, it seemed opportune to fetch it from my room, where I assumed it must be laying upon the table. With a few words I invited the friend to go on with his wife, while I collected the missing item. I turned around; but I had barely gone ten steps, when I felt, upon searching, the pipe in my pocket. And so it came to pass that the others saw me again with clouds of smoke thrusting from the pipe before even a whole minute had passed. âYes it really was on the table', I explained, prompted by an incomprehensible whim. Something arose in the man's face resembling someone who has just woken from a deep sleep, having not yet worked out where he actually is. We walked on, and the conversation took its course. Somewhat later I steered it back to the interlude. âHow come', I asked, âyou didn't notice? After all, what I claimed was

impossible.' â âThat's right', answered the man, after a short pause. âI did want to say something. But then I thought to myself: it must be true. Why should he lie to me?'

F

or the first time I was alone with my beloved in an unfamiliar village. I waited in front of my night's lodgings, which weren't hers. We still wanted to take an evening walk. While waiting, I walked up and down the village street. There I saw in the distance, between trees, a light. âThis light', so I thought to myself, âsays nothing to those who have it before their eyes every evening. It may belong to a lighthouse or a farmyard. But to me, the stranger here, it speaks volumes.' And with that I turned around, to pace down the street again. I kept this up for some time, and whenever I turned back after a while, the light, between the trees, lured my gaze. But there came a moment when it requested that I stop. That was shortly before the beloved found me again. I turned myself around once more and realised: the light that I had spotted over the flat earth had been the moon, moving slowly up over the distant tree tops.

â

Translated by Sam Dolbear and Esther Leslie

.

Unpublished in Benjamin's lifetime;

Gesammelte Schriften IV

, 755â7. Also translated in

Walter Benjamin's Archive

. According to the notes in the

Gesammelte Schriften

, Gershom Scholem claimed these stories were probably written between 1932 and 1933. The arrangement of the three texts cannot, however, be guaranteed.

The Voyage of

The Mascot

Hero With Wings (Held mit Flügel)

, 1905.

T

his is one of those tales that one gets to hear out on the sea, for which the ship's hull is the proper soundboard and the machine's pounding is the best accompaniment, and of which one should not ask whence it hails.

It was, so my friend the radio operator recounted, after the end of the war, when some ship owners got the idea of bringing back to the homeland the sailing vessels and saltpetre ships

which had been caught off guard in Chile by the catastrophe. The legal situation was simple: the ships had remained German property and now it was just a matter of readying the necessary crew in order to re-commandeer them in Valparaiso or Antofagasta. There were plenty of seafarers who hung around the harbours waiting to be taken on. But there was a small snag. How was one to get the crew to Chile? This much was obvious: they would have to board as passengers and take up their duties upon arrival. On the other hand, it was equally obvious that these were people who could hardly be kept in check by the kind of power that the captain ordinarily wields over his passengers, especially not at a time when the mood of the Kiel uprising still lingered in the sailors' bones.

No one knew this better than the people of Hamburg, including the Baton of Command of the four-masted sailing ship

The Mascot

, which consisted of an elite of determined, experienced officers. They recognised that this journey could come at a great personal cost. And because wise men plan ahead, they did not rely on their bravery alone. Rather, they attended closely to the hiring of each member in their crew. But if there was a tall chap among the recruits whose papers weren't completely in order, and whose physical state left much to be desired, then it would be overly hasty to blame his presence solely on the commander's negligence. Why this is will become clear later on.

They were barely fifty miles out of Cuxhaven when certain things became evident that bade ill for the crossing. Upon deck and in the cabins, even on the stairs, from early until late, there were meetings of all kinds of associations and coteries, and by the time they were off Helgoland, there were already three games clubs, a permanent boxing ring and an amateur stage, which was not recommended for sensitive folk. In the officers'

mess, where, overnight, the walls had been decorated with explicit drawings, men danced the shimmy with each other every afternoon, and in the stowage an on-board exchange had been established, whose members traded dollar notes, binoculars, nude photos, knives and passports with each other by torchlight. In short, the ship was a floating âMagic City' and â even without women â one was tempted to say that all the delights of harbour life could be produced out of thin air or, as it were, out of the ship's beams.

The captain, one of those seamen who combined only a little school-learning with much worldly wisdom, kept his nerve under these uncomfortable circumstances and he did not lose it even when one afternoon â it might have been just off Dover â Frieda, a well-built girl from Saint Pauli with a bad reputation and a cigarette in her mouth, appeared on the boat's stern. Undoubtedly there were people on board who knew where she had previously been stowed; what's more, these people were clear on the measures that were to be taken were they to receive instructions from above to remove the excess passenger.

From this point onwards, the nightly business was even more worth seeing. But it would not have been 1919 if politics had not been added to the list of on-board divertissements. There were voices which proclaimed that this expedition was to mark the start of a new life in a new world; others saw in it the long yearned-for instant when the reckoning with the rulers would finally be settled. Unmistakably, a harsher wind was blowing. It was soon discovered whence it came: it was a certain Schwinning, a tall chap of limp posture who wore his red hair parted and of whom nothing was known, except that he had travelled as a cabin attendant on various shipping routes and that he was well versed in the trade secrets of the Finnish bootleggers.

Initially he had kept to himself, but now one encountered him at every turn. Whoever listened to him had to concede that they were dealing with a shrewd agitator. And who did

not

listen in when he embroiled someone or other in a loud, contentious conversation at the âbar', such that his voice drowned out the sound of the phonograph record, or when, in the âring', he provided precise, entirely unsolicited information about the fighter's party affiliation. Thus, while the crowd gave in to the on-board amusements, he worked relentlessly on their politicisation, until finally his efforts were rewarded when he was appointed chairman of the sailors' council during a nocturnal plenary meeting.

As they entered the Panama Canal, the elections gained momentum. There was a lot to vote for: a house commission, a control committee, an on-board secretariat, a political tribunal. In short, a magnificent apparatus was set up, without causing even the slightest clash with the ship's command. However, within the revolutionary leadership disagreements arose all the more often; these disagreements were all the more vexatious given that â upon close examination â everyone belonged to the leadership. Whoever had no position could expect one from the next commission's meeting, and so not a day passed without difficulties to resolve, votes to count, resolutions to carry. But when the action committee finally detailed its plans for a surprise attack â at exactly eleven o'clock on the night after the next, the high command was to be overpowered and the ship was to be rerouted on a westerly course bound for the Galapagos â

The Mascot

had, unbeknownst to all, already passed beyond Callao. Later on these bearings would turn out to have been falsified. âLater' â that means the following morning â forty-eight hours before the planned, carefully prepared mutiny, when the four-mast

ship docked at the quay of Antofagasta, as if nothing had happened.

With that my friend stopped. The second watch came to an end. We stepped into the chart room, where some cocoa waited for us in deep stone cups. I was silent, attempting to make sense of what I had just heard. But the radio operator, who was about to take his first sip, suddenly paused and looked at me over the edge of his cup. âLeave it be,' he said. âWe didn't know what was going on at the time either. But when I ran into Schwinning some three months later in the administration building in Hamburg with a fat Virginia between his lips, coming straight from the director's office â then I fully comprehended the voyage of

The Mascot

.'

â

Translated by Sam Dolbear and Esther Leslie

.

This story has two versions, and it is likely, according to the type of paper and the typewriter, that the second version was written in conjunction with

Das Taschentuch

and

Der Reiseabend

. It is therefore probable that Benjamin wrote âThe Voyage of

The Mascot

no later than these two stories from 1932. Published in

Gesammelte Schriften IV

, 738â40.