The Story of French (18 page)

Read The Story of French Online

Authors: Jean-Benoit Nadeau,Julie Barlow

While theorists and purists were busy establishing rules for French, the language itself kept evolving in order to assimilate the new realities of science, industry and exploration. New words such as

usine

(factory),

bureaucratie, économiste, gravitation

and

azote

(nitrogen) came into usage. The French developed new adjectives such as

alarmant

(alarming) and new nouns such as

moralisme

(moralism) to describe the new philosophy and new sensibilities.

Ingénieur

(engineer) and

facteur

(mailman) took on their modern meanings. During the eighteenth century English words such as

challenge, toast

and

ticket

(originally imported from Old French into English) re-entered French, sometimes with new meanings. The influence of British parliamentarianism brought the new words

officiel

(official),

législature

(legislature) and

inconstitutionnel

(unconstitutional) into usage, as well as

club, vote, pétition

(petition) and

majorité

(majority). There were many other foreign influences on French at this time; Rousseau’s

La nouvelle Héloïse

(

The New Eloise

), for instance, popularized an old Swiss term,

chalet,

which meant “shelter” in the Franco-Provençal dialect spoken around Geneva at the time

.

It was during this period that French replaced Latin as the language of European diplomacy, although this was never stated anywhere in international law. Until 1678 almost all European treaties were written in Latin, which was considered a neutral language. That began to change after the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648, when the Austrians, who controlled the defeated Holy Roman Empire, claimed it was their prerogative that treaties be written in Latin. For the first time Latin became associated with a specific nationality. French was a defined language, so its corset of rules and definitions meant that whatever was written in French would not change its meaning a couple of years later. In 1678 the Treaty of Nijmegen was written in both French and Latin. The Treaty of Rastatt and Baden of 1714—one of three that ended the War of the Spanish Succession—was the first to be written completely in French, even though France had lost the war. The French plenipotentiary, the Duc de Villars, knew only French, so his imperial counterpart, Prince Eugene of Savoy, who knew French, accommodated him. According to Professor Agnès Walch, of the University of Artois in France, the negotiators introduced a clause specifying that although the treaty was negotiated in French, that did not constitute a precedent. This clause reappeared in other treaties in 1736 and 1748. But by the time of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the clause had disappeared, and the entire treaty was negotiated and written in French—even though the French had lost. From then on, all treaties were negotiated in French. In most European countries, with the notable exception of Britain, even diplomatic notes were written in French.

French became the language of diplomacy in Europe less because of the power of France than because of the power of French. A class of career diplomats had begun to appear at the time. Many of them were also career soldiers, and soldiers, who usually joined the military at a young age, rarely knew Latin. These career diplomats started bringing their wives to diplomatic conferences, and women of high society spoke French, so salon culture gradually spilled over into the meeting rooms. (The participants also spoke French among themselves so the servants could not understand them.) No decree ever made French the diplomatic language of Europe; its status was never official. It was all a question of usage. French remained the sole language of high diplomacy in Europe until 1919.

Social conditions also favoured the international preeminence of French. In the political system of Europe, based as it was on marriages among different dynasties, all communication between princes and princesses, people of rank, writers, and their lovers and mistresses—what Marc Fumaroli calls the “politico-diplomatic machine of the century”—was done in French. From Spain, Italy and Portugal to England, Germany, Holland, Russia and Sweden, the crowned heads studied French, corresponded in French and looked to France as an example and a model.

Young Swedish nobles had been travelling to Paris for their education for a good century before Gustav III (who ruled 1771–92) came to power, but he would become the king of francophiles. A great admirer of Voltaire, as well as of Jean Racine, Gustav had been raised in French; he read French books and spoke no other foreign language. During his reign he introduced French theatre to Sweden, where it played to full houses, and he brought in French artists to decorate his castles. He was kept abreast of the news from Versailles through Madame de Staël, the Swiss wife of a Swedish ambassador and the daughter of Louis XVI’s last finance minister, who became famous for her novels and essays. Gustav III paid an incognito visit to King Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette in Versailles in 1786 (during the French Revolution he would try in vain to arrange exile for them). Shortly after this visit Gustav resuscitated the Swedish Academy (an earlier one had been founded in 1753). The Swedish Academy is still in operation today. Its motto is “Talent and taste” and its mandate is “to further the purity, vigour and majesty of the Swedish language.”

Gustav III was an extreme case, but his taste for French was not uncommon among Europe’s crowned heads. Catherine II of Russia (ruled 1762–96) was an avid reader of the works of Voltaire and Montesquieu before she took power. For fifteen years during her reign she exchanged letters with Voltaire in which they discussed European and world events (her French was full of mistakes—it was her third language after German and Russian). Like Gustav III, she founded an academy based on the French model, for Russian writers. Historians still debate whether she was an enlightened despot or simply a tyrant. In either case, she worked hard throughout her reign to increase the grandeur of the Russian Empire and looked towards France for ideas. She imported French intellectuals, scientists, artists and industry leaders, sent teachers of French to Paris to complete their studies, imported French teachers and hosted French theatre evenings in her castles. Most of Russia’s nobility spoke French well into the nineteenth century—the nobles in Tolstoy’s

War and Peace

make comments in French on almost every page. And the link between France and Russia remained strong until the Russian Revolution of 1917.

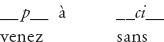

The case of Prussia’s Frederick II (ruled 1740–86) was more complicated. He was easily as passionate a francophile as Catherine II, and he only ever wanted to learn and write in one language: French. He built a new castle, Sans Souci (“free of care”), modelled on Versailles, and peppered his Court with French speakers. He had French soldiers in his army and French bureaucrats in his civil administration; he wanted to hear only French actors and plays and wrote poetry in French. He was known for including French witticisms in his messages to Voltaire during their long correspondence, like this cryptic dinner invitation:

Translation:

Venez sous p

(

venez

below P)

à sans sous ci

(

sans

below

ci

), which in French reads phonetically as

Venez souper à Sans Souci

(Come to dinner at Sans Souci).

At the beginning of Frederick’s rule he reorganized the Berlin-Brandenburg Society of Scientists in Berlin on the model of the French Academy, and it was this academy that hosted the essay contest that Rivarol and Schwab won in 1783.

But his francophilia didn’t prevent Frederick II from going to war with the French and the Russians. His ruthless expansionism, especially the way in which Prussia—along with Russia and Austria—dismantled Poland, made a serious dent in his reputation in Europe. Some historians argue that Frederick II was using the philosophes for the same purpose François I had used the Humanists for: trying to get the endorsement of public-opinion makers in order to boost his nation’s international reputation at a time when it was in an unfavourable light. In the end, Frederick’s aggressive foreign policy spelled the end of his friendship with Voltaire, and an end to the witty invitation cards.

The British were among the most ambiguous regarding their love of things French, not surprisingly, since their national identity had been built on England’s four-century-long competition with France. Yet French retained an undeniable cachet among England’s upper classes. A couple of years before defeating the French outside the walls of Quebec City, the young officer James Wolfe was sent to the City of Light for five months to dance and fence, ride and go to the opera, and improve his French. Most British officers in Quebec spoke French. Horace Walpole and David Hume wrote much of their correspondence in French. British aristocrats and members of the gentry sent their offspring on an extended journey through Europe to Italy, when they were expected to develop their taste and manners and be exposed to civilization. France, a mandatory stage of the trip, often became the sole destination.

During the eighteenth century the grand tour became a target of satirical travel writing in England. In

A Sentimental Journey

Laurence Sterne (who lived in France in 1762–64 and 1765–66) calls France a “polished nation,” though “a little too serious.” Over the course of a light-hearted romp through France, the novel’s hero turns out to be not so much widening his cultural horizons as chasing after a married woman, but through the process he encounters all the characteristics associated with the French of the period: refinement, debauchery, gallantry, wit, urbanity and self-assurance. Interestingly, the word

sentimental

entered French under Sterne’s influence; the adjective didn’t yet exist in the language, so the French translator and publisher just used the English word.

British admiration for France and French had its limits. In his

History of the French Language,

published in the nineteenth century, Ferdinand Brunot argued that the British accepted French as the language of Europe in the eighteenth century, but never accepted the idea of French cultural superiority, as many other countries did. In Britain, Brunot says, French was considered simply a “universally useful language.” The works of many British thinkers and scientists spread throughout Europe thanks to wide dissemination of their works in French translation. The philosopher John Locke became known in Italy through a French translation of his

Essay on Enlightenment,

which appeared in 1736, and the writings of Hobbes also spread through Europe in French. French started being taught as a second language at Oxford University in 1741. But according to Brunot, the English really just “wanted to learn a European language, not French per se.”

More than anything, it was this quest for a European language that drove people outside of Europe’s upper classes to learn French. Throughout the century, noble and middle-class families scrambled to find ways to enter the French-speaking world. Many French dictionaries and grammar guides were designed specifically for the provincial bourgeoisie and nobility of France, but readers outside those circles also picked them up. In the German principalities many people thought that German was good only for speaking to their horses. Parents sent children to school in French, and the schools run by Huguenots were especially popular; in a century and a half these would form the backbone of a network of

collèges

and

lycées français.

Families also imported French-speaking nannies from either France or Switzerland. In many places in Europe the French language made progress independently of any contact with France or its people. French books or French translations and French theatre were widely available in the European capitals. Francophiles were able to keep abreast of the news in France by reading one of the dozen French-language papers called

Gazette de Hollande.

According to Clyde Thogmartin of the University of Indiana, the title described any international French paper, whether it was published in London, Berlin, Monaco, Luxembourg or Geneva. (The label was a tribute to the fact that most cities in Holland had a newspaper in Dutch and another in French. The oldest version, the

Gazette de Leyde,

was founded in 1639.)