The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (32 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

Many of the problems which we have seen to be related to inequality involve adult responses to status competition. But we have also found that a number of problems affecting children are related to inequality. These include juvenile conflict, poor peer relationships and educational performance at school, childhood obesity, infant mortality and teenage pregnancy. Problems such as these are likely to reflect the way the stresses of a more unequal society – of low social status – have penetrated family life and relationships. Inequality is associated with less good outcomes of many kinds because it leads to a deterioration in the quality of relationships. An important part of the reason why countries such as Sweden, Finland and Norway score well on the UNICEF index of child wellbeing is that their welfare systems have kept rates of relative poverty low among families.

MIRROR NEURONS AND EMPATHY

To view the pursuit of greater equality as a process of shoe-horning societies into an uncomfortably tight-fitting shoe reflects a failure to recognize our human social potential. If we understood our social needs and susceptibilities we would see that a less unequal society causes dramatically lower rates of ill-health and social problems because it provides us with a better-fitting shoe.

Mirror neurons are a striking example of how our biology establishes us as deeply social beings. When we watch someone doing something, mirror neurons in our brains fire as if to produce the same actions.

338

The system is likely to have developed to serve learning by imitation. Watching a person doing a particular sequence of actions – one research paper uses the example of a curtsey – as an external observer, does not tell you how to do it yourself nearly as well as if your brain was acting

as if

you were making the same movements in sympathy. To do the same thing you need to experience it from inside.

Usually, of course, there is no visible sign of the internal processes of identification that enable us to put ourselves inside each other’s actions. However, the electrical activity triggered by these specialized neurons is detectable in the muscles. It has been suggested that similar processes might be behind our ability to empathize with each other and even behind the way people sometimes flinch while watching a film if they see pain inflicted on someone else. We react as if it was happening to us.

Though equipped with the potential to empathize very closely with others, how much we develop and use this potential is again affected by early childhood.

OXYTOCIN AND TRUST

Another example of how our biology dovetails with the nature of social relations involves a hormone called oxytocin and its effects on our willingness to trust each other. In Chapter 4 we saw that people in more unequal societies were much less likely to trust each other. Trust is of course an important ingredient in any society, but it becomes essential in modern developed societies with a high degree of interdependence.

In many different species, oxytocin affects social attachment and bonding, both bonding between mother and child, and pair-bonding between sexual partners. Its production is stimulated by physical contact during sexual intercourse, in childbirth and in breastfeeding where it controls milk let-down. However, in a number of mammalian species, including humans, it also has a role in social interaction more generally, affecting approach and avoidance behaviour.

The effects of oxytocin on people’s willingness to trust each other was tested in an experiment involving a trust game.

339

The results showed that those given oxytocin were much more likely to trust their partner. In similar experiments it was found that these effects worked both ways round: not only does receiving oxytocin make people more likely to trust, but being trusted also leads to increases in oxytocin. These effects were found even when the only evidence of trust or mistrust between people was the numerical decisions communicated through computer terminals.

340

CO-OPERATIVE PLEASURE AND PAINFUL EXCLUSION

Other experiments have shown how the sense of co-operation stimulates the reward centres in the brain. The experience of mutual co-operation, even in the absence of face-to-face contact or real communication, leads reliably to stimulation of the reward centres. The researchers suggested that the neural reward networks serve to encourage reciprocity and mutuality while resisting the temptation to act selfishly.

341

In contrast to the rewards of co-operation, experiments using brain scans have shown that the pain of social exclusion involves the same areas of the brain as are stimulated when someone experiences physical pain. Naomi Eisenberger, a psychologist at UCLA, got volunteers to play a computer bat-and-ball game with, as it seemed on the screen, two other participants.

342

The program was arranged so that after a while the other two virtual participants would start to pass the ball just between each other, so excluding the experimental subject. Brain scans showed that the areas of the brain activated by this experience of exclusion were the same areas as are activated by physical pain. In various species of monkeys these same brain areas have been found to play a role in offspring calling for, and mothers providing, maternal protection.

These connections have always been understood intuitively. When we talk about ‘hurt feelings’ or a ‘broken heart’ we recognize the connection between physical pain and the social pain caused by the breaking of close social bonds, by exclusion and ostracism. Evolutionary psychologists have shown that the tendency to ostracize people who do not co-operate, and to exclude them from the shared proceeds of co-operation, is a powerful way of maintaining high standards of co-operation.

343

And, just as the ultimatum game showed that people were willing to punish a mean allocator by rejecting – at some cost to themselves – allocations that seemed unfair, so we appear to have a desire to exclude people who do not co-operate.

Social pain is of course central to rejection and is the opposite of the pleasures – discussed earlier – of being valued or of the sense of self-realization which can come from others’ appreciation of what we have done for them. The powers of inclusion and exclusion indicate our fundamental need for social integration and are, no doubt, part of the explanation of why friendship and social involvement are so protective of health (Chapter 6).

Social class and status differences almost certainly cause similar forms of social pain. Unfairness, inequality and the rejection of co-operation are all forms of exclusion. The experiments which demonstrated the performance effects of being classified as inferior (which we saw in Chapter 8 among Indian children in different castes, in experiments with school children, and among African-American students told they were doing tests of ability) indicated the social pain related to exclusion. Part of the same picture is the social pain which sometimes triggers violence (Chapter 10) when people feel they are put down, humiliated or suffer loss of face.

For a species which thrives on friendship and enjoys co-operation and trust, which has a strong sense of fairness, which is equipped with mirror neurons allowing us to learn our way of life through a process of identification, it is clear that social structures which create relationships based on inequality, inferiority and social exclusion must inflict a great deal of social pain. In this light we can perhaps begin not only to see why more unequal societies are so socially dysfunctional but, through that, perhaps also to feel more confident that a more humane society may be a great deal more practical than the highly unequal ones in which so many of us live now.

The one who dies with most toys wins.

US bumper sticker

Over the next generation or so, politics seem likely to be dominated either by efforts to prevent runaway global warming or, if they fail, by attempts to deal with its consequences. Carbon emissions per head in rich countries are between two and five times higher than the world average. But cutting their emissions by a half or four-fifths will not be enough: world totals are already too high and allowances must be made for economic growth in poorer countries.

How might greater equality and policies to reduce carbon emissions go together? Given what inequality does to a society, and particularly how it heightens competitive consumption, it looks not only as if the two are complementary, but also that governments may be unable to make big enough cuts in carbon emissions without also reducing inequality.

SUSTAINABILITY AND THE QUALITY OF LIFE

Ever since the Brandt Report in 1980 people have suggested that social and environmental sustainability go together. It is fortunate that just when the human species discovers that the environment cannot absorb further increases in emissions, we also learn that further economic growth in the developed world no longer improves health, happiness or measures of wellbeing. On top of that, we have now seen that there are ways of improving the quality of life in rich countries without further economic growth.

But if we do not need to consume more, what would be the consequences of consuming less? Would making the necessary cuts in carbon emissions mean reducing present material living standards below what people in the rich world could accept as an adequate quality of life? Is sustainability compatible with retaining our quality of life?

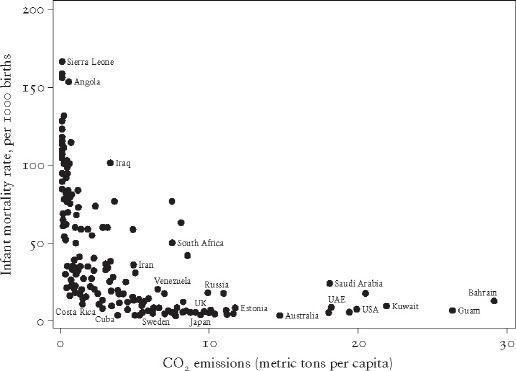

One starting point for answering this question is Figure 15.1 which shows that low infant mortality rates can be achieved without high levels of carbon emissions. Clearly many countries achieve levels of infant mortality as low as the richest countries while producing much less carbon. However, a more comprehensive answer to the question comes from the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), which analysed data relating the quality of life in each country to the size of the ecological footprint per head of population.

345

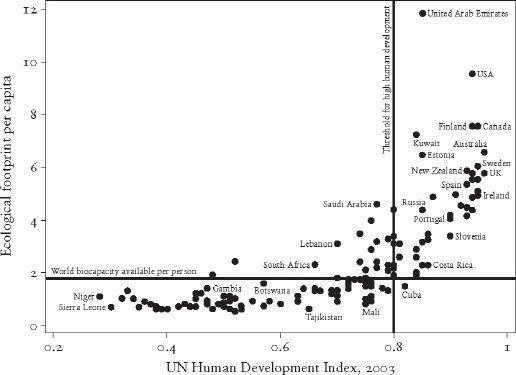

To measure the quality of life they used the UN Human Development Index (HDI) which combines life expectancy, education and Gross Domestic Product per capita. Figure 15.2 uses WWF data to show the relation between each country’s ecological footprint per head and its score on the UN Human Development Index. Scarcely a single country combines a quality of life (above the WWF threshold of 0.8 on the HDI) with an ecological footprint which is globally sustainable. Cuba is the only one which does so. Despite its much lower income levels, its life expectancy and infant mortality rates are almost identical to those in the United States.

Figure 15.1

Low infant mortality can be achieved without high carbon emissions.

344