The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (65 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

According to ancient German legend, the first runes were discovered by the Norse god Odin, who bravely underwent a painful ritual of self-sacrifice in the pursuit of knowledge. After piercing his side with a spear, Odin hung for nine days from the branches of the Scandinavian tree of life. As his body moved in the wind, some twigs were dislodged, and they fell to the ground in a pattern that formed the runic alphabet.

Of course, the historical evidence paints a slightly different picture, suggesting that runes were invented by mortals in Denmark or Sweden, sometime around 200

A.D

. The earliest Germanic runes (known as

futhark

runes) were extremely primitive, often consisting of nothing more than a series of straight lines arranged in different combinations. They were used for a variety of non-magical purposes, including writing letters, setting down instructions, and identifying the owners of property. One of the best known runic inscriptions, from the Sigurd runestone in Sweden, commemorates the construction of a bridge.

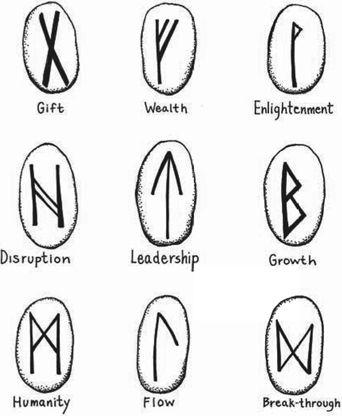

A

selection of Nordic rune stones and their traditional interpretations

. (

photo credit 71.1

)

From the beginning, however, runes were also invested with magical significance. The Vikings and other Germanic peoples used runes as tools of

divination

;carved runes into their swords to make themselves invincible in battle; inscribed them on stone

amulets

to ward off disease and sorcery; and chiseled them into burial markers to discourage grave robbers. Starting around 450

A.D

., runes also became popular in England, where Anglo-Saxon

magicians

used them to make

amulets

and predict the future.

To date, more than four thousand runic inscriptions have been found throughout Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and England, most of them dating from the height of the Viking period around 800

A.D

. Runes have been located not just on weapons, amulets, and gravestones, but also on coins, jewelry, and mysterious slabs of wood. There are even some runes inscribed on the rim of Professor Dumbledore’s magical pensieve.

The ancient practice of using runes to foretell the future, known as rune casting, has experienced a remarkable revival of popularity in the past century. When the Vikings and Anglo-Saxons used runes for divination, they began by carving runic symbols into thin strips of wood cut from the branches of fruit-bearing trees. These strips were tossed or “cast” at random onto a clean white cloth, and then a seer or rune master would select three (while gazing at the sky for divine inspiration) and interpret their meaning. Today, an aspiring fortune-teller can purchase a set of sixteen to thirty-three “rune stones”—round or oblong tiles made of stone or clay and inscribed with runic characters. In a simple modern rune-casting system, the stones are mixed in a bag and then scattered onto a flat surface. Some rune casters “read” all stones that come out face up. Others close their eyes and select just three, representing past, present, and future. While some rune casters base their readings only on what scholars know about the ancient meanings of the symbols, many have invented their own systems of interpretation.

Unfortunately, the widespread popularity of the Latin alphabet has led to a dramatic decline in runic literacy rates over the last millennium. Today, despite the best efforts of institutions like Hogwarts, only a handful of wizards and muggles can still read these mysterious characters that once cost poor Odin so much.

ost of us know the salamander as a cute, colorful little amphibian we might encounter during a walk in the woods. If you’ve seen one, you probably stopped for a moment to examine it and then resumed your journey without a second thought. In centuries past, however, these tiny, lizard-like creatures were likely to attract exclamations of amazement and delight. Like those Hagrid brings to Care of Magical Creatures class, the salamanders of ancient times were reputed to frolic among the hottest flames without getting burned. Not only could they emerge from the fire unscathed, legend held, but their icy skin could even extinguish flames on contact.

ost of us know the salamander as a cute, colorful little amphibian we might encounter during a walk in the woods. If you’ve seen one, you probably stopped for a moment to examine it and then resumed your journey without a second thought. In centuries past, however, these tiny, lizard-like creatures were likely to attract exclamations of amazement and delight. Like those Hagrid brings to Care of Magical Creatures class, the salamanders of ancient times were reputed to frolic among the hottest flames without getting burned. Not only could they emerge from the fire unscathed, legend held, but their icy skin could even extinguish flames on contact.

The fireproof qualities of the marvelous salamander were discussed with enthusiasm in ancient Greece and Rome. In his

Natural History

, the Latin writer Pliny reported that the brave salamander was so inspired by the sight of fire that he would charge headlong toward the flames as if to vanquish an enemy. More fanciful folk suggested that salamanders might be brought to the rescue when a house was burning down! Other ancient thinkers, however, cast a skeptical eye on these notions, and decided to do a little experimentation. The Roman physician Galen and others told of seizing unsuspecting salamanders, throwing them into the flames, and watching them burn to a crisp.

Despite reports of several such experiments, belief in the salamander’s immunity to fire persisted well into the Renaissance, when cloth labeled as “salamander wool,” said to be incombustible, was sold at a hefty price. Such cloth was used to make clothes for people whose occupations brought them near open flames, and for making envelopes to mail precious (and flammable) items. While there is no such thing as salamander wool (salamanders don’t even have fur), buyers of this cloth were not completely out of luck. The material

was

actually flame resistant. Apparently, merchants discovered that their fabric could command a higher price if it was said to come from the legendary “lizard” rather than its true source—the mineral asbestos.

Although there’s no truth to the notion that salamanders can survive fire, the source of this belief is clear enough. People do actually see salamanders scampering around in the ashes. That’s because the tiny creatures like to hibernate in old logs. When those logs get thrown into the fireplace, along go the salamanders who call them home. Awakened in such an unpleasant fashion, salamanders may occasionally be able to escape from the flames, protected for a second or two by the natural secretions of their skin. Although such a feat is hardly miraculous, it has earned the salamander a place in the popular imagination, as well as in the dictionary—in addition to being a little amphibian, a salamander is “an object, such as a poker, used in a fire or capable of withstanding heat.”