The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (31 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

Perhaps because carpets were not widely used in Europe and North America until the late nineteenth century, the flying variety have never played a central role in Western mythology and folklore. (Indeed, most Westerners mistakenly associate flying carpets primarily with the story of Aladdin, a tale in which they never actually appear.) Instead of flying rugs, Western magicians and heroes have relied on a host of other levitating objects ranging from winged sandals to hovering suitcases to great glass elevators. One popular American children’s story even features a flying sofa. And then, of course, there are

broomsticks

, such as Harry’s beloved Firebolt, which could probably fly rings around any carpet foolish enough to float onto a Quidditch field. It’s just too bad most broomsticks are single-passenger vehicles. If Harry ever amasses an army like King Solomon’s, he’ll have to borrow the keys to Mr. Weasley’s flying car.

ach time Harry enters the Forbidden Forest, he feels a certain sense of dread. And well he should, for he and his classmates have been warned repeatedly of the dangers that lurk within the dark woods. Just as the forests of our favorite fairy tales are populated by

ach time Harry enters the Forbidden Forest, he feels a certain sense of dread. And well he should, for he and his classmates have been warned repeatedly of the dangers that lurk within the dark woods. Just as the forests of our favorite fairy tales are populated by

witches

and ogres,

goblins

and

trolls

, so the Hogwarts wood is alive with monsters of every description. What makes these places so frightening—and also so exciting—is that you never know what lurks behind the next tree.

The forest has always been associated with risk—the perils of getting lost, encountering evil strangers, or being devoured by wild beasts. In the first century

B.C.

, Julius Caesar wrote of travelers who walked through a terrible forest for sixty days without ever coming to its edge, eventually emerging to describe encounters with bizarre creatures that had long been extinct elsewhere. To the ancient Romans, the clearing and cultivation of land and the construction of cities represented the triumph of civilization over barbarism. A pleasing landscape was one that had been shaped by the hand of man, while the untamed wilderness was viewed as ugly and frightful. The best way the Roman historian Tacitus knew to distinguish his cultured countrymen from the Germans they despised was to note that their foes were “forest dwellers.”

Centuries later in England, views of the forest were much the same. The woods were thought to be the proper home of animals rather than men, and any man who dwelt in them was assumed to be crude and brutal. A seventeenth-century philosopher contrasted “civil and rational,” city dwellers with the “irrational, untaught” inhabitants of woods and forests. (Some folks at Hogwarts seem to hold the same opinion about Hagrid, who is in many ways a creature of the forest and lives on its edge.) The forest stood for all that was strange, suspicious, and outside the boundaries of normal human experience. Indeed, the English words “foreign” and “forest” both derive from the same Latin root,

foris

, meaning “outside.”

To those of us who enjoy a pleasant walk in the woods or a camping trip now and then, such negative assessments of the forest may seem harsh. But they did have some basis in reality. In medieval and early modern Europe, forests were often populated by vagrants and outlaws who had little respect for life or law. For anyone who wanted to hide from the authorities or conduct illicit business, a densely wooded area provided an ideal place to avoid detection. This bit of history helps to explain why so many fairy tales contain characters like the witch who captures Hansel and Gretel or Little Red Riding Hood’s big bad wolf—sinister villains who lurk in the woods, waiting to prey upon the innocent. It is therefore very much in keeping with tradition that Lord Voldemort chooses to dwell in the forest while regaining his strength.

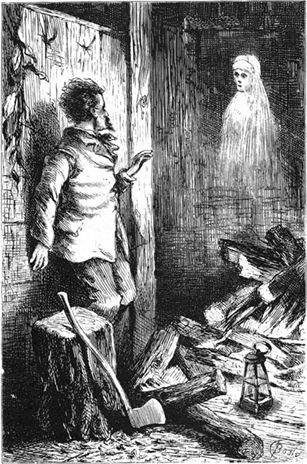

ave you ever wondered where ghosts really come from? Or why some dearly departed souls, like Moaning Myrtle and Professor Binns, float about the earth, while others simply slumber away in a nice, peaceful grave? If you have, you’re not alone. Ghosts and ghost stories have played an important role in the folklore, literature, and religion of virtually every civilization.

ave you ever wondered where ghosts really come from? Or why some dearly departed souls, like Moaning Myrtle and Professor Binns, float about the earth, while others simply slumber away in a nice, peaceful grave? If you have, you’re not alone. Ghosts and ghost stories have played an important role in the folklore, literature, and religion of virtually every civilization.

Ghosts manifest themselves in many forms. The most basic and universal type of ghost is the apparition, or disembodied spirit. Some apparitions appear to be composed of a pale mistlike vapor; but many others resemble perfectly normal, flesh-and-blood human beings. European folklore is filled with tales of all-too-human-looking ghosts, who eat, drink, and carry out most of the standard bodily functions of living people. Often, the ghostly nature of such specters is revealed only by their uncanny ability to vanish into thin air, or by the odd musty or rotting odor that some ghosts leave behind.

In ancient Greece and Rome, the spirits of the dead often took the form of dark shadows, strange black patches, or invisible,

poltergeist

-like presences. The ancient Egyptians believed the dead could return in their own reanimated bodies, and many other cultures have believed that ghosts could appear as

demons

, animals, and even plants.

Most ancient societies, in both the Eastern and Western world, took it for granted that ghosts were a very real—and very natural—phenomenon, and many cultures held festivals throughout the year to maintain good relations with the dead. Perhaps the strangest ancient festival of the dead was the Roman feast of Lemuralia, held every spring. During Lemuralia, Roman homeowners would get up in the middle of night and march around their living rooms, strewing a trail of black beans behind them. “With these beans,” the men would intone seriously, “I buy back myself and my family.” They would circle the room, trailing their beans and repeating this phrase nine times, to ensure that the spirits of the dead had plenty of time to gather up their offerings. Then the homeowner performing the ritual would clash a heavy bronze cymbal and cry out “Spirits of my ancestors depart,” after which all restless ghosts were believed to go quietly away until the following year.

As the relatively friendly character of this ritual indicates, most ancient ghosts were not so much feared, as honored. Today, however, most ghost lore—whether presented as fact or fiction—depicts ghosts as frightening, unnatural creatures, who only appear when the spirit of a dead person is restless or uneasy for some reason. Some restless spirits, like the character of Jacob Marley in Charles Dickens’

A Christmas Carol

, are doomed to haunt mankind because of the sins they committed in life. Others walk the Earth because they have met with some sort of violent or unexpected end. Beamish Hall, in County Durham, England, for example, is said to be haunted by the ghost of an unfortunate young woman who suffocated to death while hiding in a trunk. (Legend has it she was trying to avoid an unwanted, arranged marriage. One can only hope that her fiancé was really as bad as she thought!)

Most of the ghosts at Hogwarts clearly suffered similarly brutal or tragic ends. Nearly Headless Nick’s gruesome demise may actually have been inspired by the case of the fourteenth-century Earl of Lancaster, who is said to haunt England’s Dunstanburgh Hall in retaliation for his own botched beheading. According to witnesses, it took an inexperienced executioner eleven ax strokes to sever the Earl’s head from his body, and even hardened soldiers fainted at the sight!