The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (19 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

Some poorly trained witches and wizards—and most nonmagical folk—also use the word “charm” to describe any small, portable object with magical properties. Rabbits’ feet, four-leaf clovers, and iron horseshoes are all frequently called “lucky charms,” but any serious magician would scoff at such a claim. These sorts of magical artifacts can be more precisely identified as either

amulets

(objects that provide magical protection) or

talismans

(objects that endow a person with some new magical ability). The so-called charms that hang from modern “charm bracelets” are usually purely ornamental symbols of love or friendship, possessing no magical powers.

As Hermione would be happy to tell you, the best place to find authentic charms is in books. So if you find yourself wanting a cheering charm for a friend who’s feeling blue or a scouring charm to take care of a really nasty mess, just check the Hogwarts library for a copy of

Olde and Forgotten Bewitchments and Charmes

. But make sure you’ve picked just the right charm for the job and that you know how to pronounce every word. Otherwise, you may end up like Professor Dumbledore’s ne’er-do-well brother, Aberforth, who was publicly humiliated for practicing inappropriate charms on a goat.

he Ministry of Magic considers certain magical creatures a suitable part of a Hogwarts education. The gentle

he Ministry of Magic considers certain magical creatures a suitable part of a Hogwarts education. The gentle

unicorn

, cuddly niffler, and fragile bowtruckle all make the grade. But many of the beasts in Hagrid’s lesson plans are deemed too dangerous for underage

witches

and

wizards

to experience firsthand. Such is the case for the fascinating but ferocious Chimera, a monster that Hagrid hopes to breed one day.

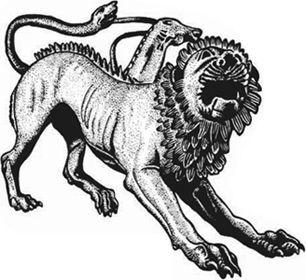

Like her siblings the

Sphinx

and the three-headed dog Cerberus (

Fluffy

, to his pals), the Chimera was an ancient monster of Greek mythology. The earliest source on the subject, the poet Homer, tells us that the Chimera (Greek for “she-goat”) was a three-part, fire-breathing terror, “in the fore part a lion, in the hinder a serpent, and in the middle a goat—breathing forth in terrible manner the force of blazing fire.” Hesiod, writing a century later, agreed that the Chimera was “a creature fearful,” and added to her ferocity by giving her three heads (lion, goat, and snake) instead of one. Wherever she chose to roam, the Chimera ravaged the landscape, devouring man and beast alike.

When examining the pedigrees of monsters it’s not always easy to tell which traits came from which side of the family. In the case of the Chimera, though, it’s pretty obvious where she got her violent temper and talent for flame-throwing. Her father, Typhon, was one of the most ferocious and spectacular

giants

of Greek mythology. The offspring of Gaia and Tartarus, Typhon towered over mountains, and his hundred heads nearly reached the stars. Streams of fire gushed from his eyes, snakes sprouted like vines from his shoulders, and he strode the world atop legs of coiled serpents. At his most daring he attacked the gods of Mt. Olympus, sending them fleeing under a barrage of fire and boulders. Even the great Zeus was wounded by the fearsome giant. However, the chief of the gods soon took revenge. As Typhon strode across the Sea of Sicily, Zeus pelted him with thunderbolts and then dropped Mt. Etna on top of him, imprisoning him forever. It is because Typhon lived, legend has it, that Mt. Etna became a volcano and still spews fire and lava to this day.

Echidna, the Chimera’s mother, was renowned for her great beauty—at least from the waist up. “Half of her is a nymph with a fair face and eyes glancing,” wrote the poet Hesiod, “but the other half is a monstrous snake, terrible, enormous and squirming and voracious.” Apparently this was just what Typhon was looking for in a mate, for together they raised a formidable family of monsters, among them Cerberus, the

Sphinx

, the Hydra (a nine-headed snake who grew two new heads for every one lopped off), and the runt of the litter, the ferocious hound Orthos, who had but two heads and a serpent for a tail. Echidna, like Typhon, was said to be immortal and dwell in a subterranean cave, never growing old and rarely seeing gods, mortals, or the light of day.

According to legend, the Chimera was the offspring of the monsters Typhon (dad) and Echidna (mom). As a baby she was kept as a pet by the king of Caria, an ancient land near present-day Turkey. However, there was no controlling or housebreaking the beast and she soon went on a rampage, invading the neighboring country of Lycia. Belching fire and smoke, scorching everything in her path, and carrying off women, children, and cattle, the Chimera was unstoppable.

Just at that time, the story goes, a handsome youth named Bellerophon presented himself at the court of Iobates, King of Lycia. Bellerophon had been sent by his father-in-law, King Proteus, and he was given royal reception. But when Iobates read the sealed letter of introduction that Bellerophon had brought with him, he discovered that instead of honoring the young man, he was supposed to kill him. Reluctant to do so himself, the king gave Bellerophon the seemingly impossible task of slaying the Chimera, feeling certain the young man would be killed in the battle.

Bellerophon accepted the challenge and, astride the winged horse Pegasus, flew to the monster’s lair. But killing the Chimera was no easy task. Torrents of fire kept horse and rider at bay and arrows were useless against the strong and nimble beast. Then Bellerophon hit upon an ingenious idea. He affixed a chunk of lead to the tip of a long spear and, urging Pegasus as close to the monster as possible, he dropped the lead into the Chimera’s blazing mouth. Instantly, the lead turned molten and slid down the monster’s throat, choking her to death.

The story of the Chimera—the awful devastation she caused and her eventual defeat at the hands of Bellerophon and Pegasus—was told and embellished by many Greek and Roman writers. During the Middle Ages, the monster became a symbol of evil. The witch-hunters Kramer and Sprenger (see

Witch Persecution

), for example, compared the three parts of the Chimera—lion, goat, and serpent—to an evil woman who was “beautiful to look upon, contaminating to the touch, and deadly to keep.” Today, the word “chimera” is used more generally to mean any type of hybrid or composite creature such as the

hippogriff

(eagle, lion, horse) or the

centaur

(man, horse). It also means “an impossible idea,” “a pipe dream,” or something that can be imagined but never achieved. Whether Hagrid’s desire to bring a Chimera to class is itself a chimera remains to be seen.