The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (17 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

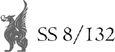

Many people find cats fascinating, and folklore abounds with stories that attribute meaning to just about any little thing a cat might do. One legend has it that rain may be expected when cats are frisky; another claims this is true only if a cat passes a paw over both ears while washing. Guests can be expected when a cat trims its whiskers, but when it stretches its paws toward the fire, those approaching the house are strangers. A cat sneezing near a bride on her wedding day predicts a happy marriage, but three sneezes mean colds for everyone in the house. And in case you’re wondering whether keeping company with a black cat really will bring bad luck, it depends on where you live. Americans tend to shun black cats, but in England, they’re considered lucky. And in Elizabethan times, neither black nor white but brindled (tabby) cats were most often associated with witches, like the famous three in Shakespeare’s

Macbeth

who take the fact that “thrice the brindled cat hath mewed” as a signal for action. No one can fully account for the way cat colors have gone in and out of style over the centuries. So perhaps it’s safest to follow Welsh tradition, which holds that those who keep both a coal black cat and a snowy white one are the luckiest of all.

Why have cats been so passionately loved and hated? Many cat superstitions can be traced to observations that reflect some pretty basic truths about cats. Like Hermione’s cat Crookshanks, most felines have a strong dislike of rats. Some say Egyptian cat worship stemmed from the fact that cats protected granaries and other places where food was stored from becoming overrun by rodents. And having observed cats killing deadly vipers, Egyptians came to believe the cat was the natural enemy of the

snake

, a traditional symbol of evil. The cat’s excellent night vision, and the way its eyes can eerily reflect light, led to the idea that cats were clairvoyant: If they could see in the dark, why couldn’t they read minds or look into the future? The static electricity in cats’ fur—which changes in quality when the air is particularly dry or moist—was translated into an ability to forecast the weather. And the tendency of many cats to appear aloof and indifferent to humans caused some people to regard them as “otherworldly” creatures with secret lives, or as scheming tricksters just waiting for the right moment to pounce on a sleeping baby or report an overheard conversation. So if you sometimes like to pat the head of a soft, purring cat and whisper a secret into its ear, you might want to consider telling a dog instead.

Some people suspected that witches disguised themselves as cats to listen in on private conversations

.

t first glance, a cauldron may appear to be just an oversized cookpot. But in the right (or wrong) hands, it can be a magical artifact of extraordinary power. With a cauldron, a skilled

t first glance, a cauldron may appear to be just an oversized cookpot. But in the right (or wrong) hands, it can be a magical artifact of extraordinary power. With a cauldron, a skilled

witch

or

wizard

can brew

potions

, predict the future, provide an endless supply of food to an unlimited number of guests, grant youth and strength, or bestow knowledge and wisdom.

Early cauldrons came in many shapes and sizes and were made of bronze, copper, pewter (like Harry’s), stone, and later of cast iron. In medieval times, the cauldron was at the center of almost every household activity. It was used for cooking, brewing medicines, washing and dyeing clothing, making soap and candles, and transporting both water and fire. A large family might own only a single cauldron, used for all of these purposes.

In some cultures, cauldrons were part of religious rituals. The ancient Celts kept their gods content with offerings of fine gold and silver jewelry, which they placed in a cauldron that was then sunk in a body of water. One such cauldron was later found in a lake in France and plundered by some very happy Romans. The famed Gundestrup cauldron, which was discovered in a peat bog in Denmark in 1891, is made almost entirely of pure silver and features depictions of gods, plants, and fantastic animals (see

Stag

). It dates from the first century

B.C.

and was probably used for human sacrifice.

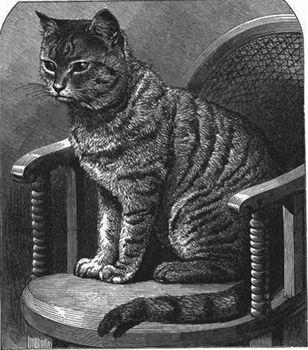

The best-known use for cauldrons, however, is as a tool for witches. The association dates back to ancient times. In Greek mythology, the witch Medea promised her husband that she would extend the life of his aging and debilitated father. She mixed magic herbs with parts from “animals tenacious of life” (notably tortoises) in a cauldron, then cut the old man’s throat and poured her concoction into his wound. Medea’s potion restored her father-in-law to the vigor of his youth.

The association between witches and cauldrons dates back to ancient Greece and Rome. Here, an old witch instructs her apprentice in the art of brewing potions

. (

photo credit 10.1

)

Perhaps the most famous cauldron of all belonged to the trio of witches that helped lead Shakespeare’s famous character Macbeth to his doom. Accosted by Macbeth with demands that they predict his future, the witches prepared a most unappetizing brew, tossing into their cauldron a

dragon

’s scale, a wolf’s tooth, a lizard’s leg, eye of newt, and toe of frog. Using this unique stew and the famous incantation “double, double, toil and trouble, fire burn and cauldron bubble,” the witches called forth three spirits that offered accurate—if cleverly misleading—

prophecies

.

The cauldron also figures prominently in Irish, Welsh, and Celtic mythology, in which it is considered a magical object holding power over life itself. The mouth of the cauldron is viewed as a gateway to the underworld, from which new life emerges and to which the dying return. The cauldron of Pwyll, Welsh lord of the underworld, was said to grant immortality. Some legends suggest that King Arthur and his knights once attempted to steal this cauldron. Legend also holds that the Irish hero Bran had a cauldron with the power to bring the dead back to life, which he gave to the king of Ireland. The corrupt king then used this magical vessel to create an inexhaustible supply of undead soldiers. These soldiers were mute, in order to prevent them from revealing the secrets of the afterlife. Accounts of battles describe how various body parts from soldiers cut down in battle were tossed into the cauldron, from which the bodies immediately emerged, whole and ready to fight another day. The Irish king was defeated only when Bran’s half-brother leapt into the cauldron, sacrificing his own life to destroy the vessel, which was not meant to hold living beings.