The Sexual History of London (22 page)

Read The Sexual History of London Online

Authors: Catharine Arnold

Skittles proved to be the most celebrated courtesan of the period. So called because her first job was working at a bowling alley in Park Lane, and because she rolled over easily, Skittles started life in Liverpool as plain Catherine Walters, born the daughter of an Irish customs officer in Toxteth in 1839. In 1856, at the age of seventeen, Catherine arrived in London to seek her fortune. After five years working the Haymarket, she met the Marquess of Hartington (later the 8th Duke of Devonshire), an aspiring Liberal MP, who fell madly in love with her and set her up in a house in Mayfair complete with servants, carriages and an annuity of £2000 a year.

Skittles swiftly became the darling of the London scene: Sir Edwin Landseer painted her portrait, and hung it in the Royal Academy; the future poet laureate Alfred Austen and Wilfred Scrawen Blunt dedicated poems to her; even the formidable Prime Minister, William Gladstone, who had a soft spot for prostitutes, invited her to tea. Skittles was smart enough to understand that her quirky character was a major factor of her charm. She romanticized her origins, hammed up her Scouse accent and entranced her admirers with a winning combination of classical beauty and a mouth like a docker. She also took the opportunity to improve herself. Intelligent, witty and well read, she was interested in art, music and religion. One of Skittles' greatest assets was her discretion: she was reputed to have had affairs with half the crowned heads of Europe, but never confirmed or denied these rumours. She really was one of the greatest

grandes horizontales

, in a direct line of descent from Nell Gwyn, and as such it was only fitting that eventually she became the mistress of her greatest conquest, the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII.

If Skittles was the last true courtesan, Edward was the last of our promiscuous monarchs, having had affairs throughout his married life, with the acquiescence of his long-suffering wife, Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Edward's name was linked with all the great beauties of the day, including the actress Lily Langtry, Alice Keppel (great-grandmother of Camilla Parker Bowles) and Lady Randolph Churchill, mother of Sir Winston. Skittles retired in 1890, a wealthy woman, and clearly a healthy one too, as she lived on until 1920 in her splendid Mayfair home, a survivor of another age.

Mayhew regarded high-class courtesans such as Skittles as a bad influence, railing that these girls set a poor example to the lower orders with their dazzling extravagance and were nothing more than âtubercules on the social system'.

25

But these were the top whores. Whatever Mayhew's moral outrage, these women operated without fear of criminal prosecution. The Metropolitan police left them alone: it would have been impossible to do otherwise, considering that their clients included aristocrats, MPs, barristers and military commanders. So, as in previous generations, the kept women were almost immune to prosecution and were most likely to quit the life through a prestigious marriage or comfortable retirement.

Houses of assignation, which have been considered in earlier chapters, remained a popular feature of London's sexual life. It was in these establishments, wrote Mayhew, that âladies of intrigue' found their pleasure. Ladies of intrigue, he wrote, were âmarried women who have connection with other men than their husbands, and unmarried women who gratify their passion secretly',

26

and who âmerely to satisfy their animal instincts, intrigue with men whom they do not truly love'.

27

Mayhew had heard of a house of assignation in Regent Street, but dealt with it in a cursory fashion, since âthis sort of clandestine prostitution is not nearly so common in England as in France and other parts of the continent, where chastity and faithfulness among married women are remarkable for their absence'.

28

He did pause to relate one anecdote which revealed how these houses operated.

The story concerns a high-society woman, let us call her Lady Susan, who, married to a man of considerable wealth, nevertheless found that she was unhappy with him, and eventually came to the conclusion that she was trapped in a marriage with a man who made her miserable. Lady Susan was naturally passionate, and, desperate for an affair, decided to visit a house in Mayfair that one of her female friends had mentioned some time before. Ordering a cab, she was driven to the house and knocked at the door. When it opened, there was no need for her to explain herself; the nature of her visit was understood. Lady Susan was shown upstairs into a handsomely appointed sitting room, there to await the arrival of her unknown paramour.

After a little time, the door opened and a gentleman appeared. The curtains were drawn and the blinds turned down, so that the entire room was pervaded with a dim, soft light which prevented her from seeing him clearly. The man approached Lady Susan and began to speak softly on some indifferent subject. Lady Susan listened for a moment and then gave a cry of astonishment as she realized that the voice was that of her husband. He, equally confused, realized that he had accidentally met his own wife in a house of ill fame â his wife, whom he had treated unkindly and cruelly, leaving her to languish at home while he roamed about London. This tryst with a twist had a successful outcome, however, as it concluded with a reconciliation when both husband and wife admitted that they were equally to blame.

Â

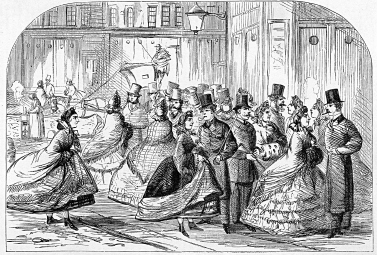

Every evening, any stranger to London could not fail to be struck by the extraordinary scenes as the dense throng of people crowded along London Bridge, Fleet Street, Cheapside, Holborn, Oxford Street and the Strand. But nothing made more of a vivid impression than the gaiety of Regent Street and the Haymarket, with the architectural splendour of its aristocratic streets, the brilliant illumination of the shops, cafés and concert rooms, and the troops of elegantly dressed courtesans rustling in silks and satins, and waving to everyone, from the ragged crossing-sweeper and the tattered shoe-black to the high-bred gentlemen of fashion and sons of the nobility.

Prostitutes offer their services in the Haymarket in London's West End

c.

1860.

It was to this part of the West End that London's prostitutes were drawn like moths to a flame. Every form of prostitute was to be found in the Haymarket: beautiful girls with blooming cheeks, newly up from the country; pale, elegant milliners; French girls, notable for their dark silk coats and white or dark silk bonnets, trimmed with brightly coloured ribbons or flowers, who patrolled a beat on Pall Mall so that they could hover outside the gentlemen's clubs; and, of course, the bloated old women who had grown grey in the service of prostitution, or been invalided out through venereal disease.

The Haymarket was the heart of the theatre district, so there were always rich pickings to be had as the crowds spilled out onto the pavements, aroused by the dramatic spectacle witnessed on stage and eager for more excitement. By the 1850s, the Haymarket was also the heart of London's nightlife, offering food, drink and entertainment to every level of society, from expensive supper clubs such as Kate Hamilton's, the Turkish divans (similar to today's cigar bars), where men gathered to smoke tobacco and pick up women, and the night houses, where patrons paid over the odds for dinner while the girls worked the room. Even the kept women emerged briefly to visit the supper rooms, where their fashionable carriages might be seen drawn up outside, or to attend the Alhambra Music Hall.

âThe Halls' as they were known were the Victorian equivalent of the notorious Restoration playhouses, bawdy, smoky, genial dens of iniquity popular with all social classes, who flocked to watch a succession of daring variety acts, consisting of coarse popular songs and saucy comedians. The Alhambra was inevitably popular with prostitutes, both for work and recreation. It was a great lofty building, ablaze with light, gorgeous with colour and gilding. Wine, spirits and ale flowed, and everybody appeared well dressed, the gaslight making even tawdry finery look like elegant costumes. The quality lounged on the balcony and in the boxes, watching the performances, which according to one commentator were designed to outrage moral decency for the amusement of those patrons who were so depraved that they required constant stimulation.

In the haze of tobacco smoke, the heat and glare of gas, the excitement of strong drink and the unrestrained licence of many of the most prominent visitors, a âballet' would be performed by a throng of bold women, two-score half-naked girls and middle-aged women, all painted and raddled, brassy smiles plastered across their weary faces as they skipped and pranced in response to the applause that greeted an indecent gesture or an obscene leer; these were the dancers who were willing to divest themselves of the last remaining shreds of modesty â and most of their clothes as well.

These acts drummed up trade for the working girls who trawled the halls, just as their orange girl predecessors had done in previous generations. Here, flaunting, talking, laughing, not merely tolerated but actively encouraged, they were treated to rich food and fine wines at their admirers' expense. These were the âgay' ladies, and the West End was their world.

For all his reforming zeal, even Mayhew was quite taken with the vivid scenes in the Haymarket and recorded the beautiful young women in their feathers and lace with the enthusiasm of a tourist. Other commentators were less forgiving, such as the columnist in

Household Words

who regarded the same part of London as âblack-guard, ruffianly and deeply dangerous':

If Piccadilly may be termed an artery of the metropolis, most assuredly that strip of pavement between the top of the Haymarket and the Regent Circus is one of its ulcers. It is always an offensive place to pass, even in the daytime; but at night it is absolutely hideous, with its sparring snobs, and flashing satins, and sporting gents [âsporting' was a euphemism for âon the pull'], and painted cheeks, and brandy-sparkling eyes, and bad tobacco, and hoarse horse-laughs, and loud indecency. From an extensive continental experience of cities, I can take personally an example from three quarters of the globe; but I have never anywhere witnessed such open ruffianism and wretched profligacy as rings along those Piccadilly flagstones any time after the gas is lighted.

29

Meanwhile, the sexual compulsive âWalter', who seems to have been a difficult man to shock, professed himself astonished by the sight of women relieving themselves openly on a street near the Strand which was

dark of a night and a favourite place for doxies to go to relieve their bladders. The police took no notice of such trifles, provided it was not done in the greater thoroughfare (although I have seen at night women do it openly in the gutters in the Strand); in the particular street I have seen them pissing almost in rows; yet they mostly went in twos to do that job, for a woman likes a screen, one usually standing up till the other has finished, and then taking her turn. Indeed the pissing in all bye-streets of the Strand was continuous, for although the population of London was only half of what it is now, the number of gay ladies seemed double there.

30

Mayhew disapproved of the kept women, the pampered soiled doves of St John's Wood, but he was rather more sympathetic towards the West End girls or âCyprians'. Prone to sentimentality, he cast them as ephemeral butterflies with an uncertain future. He classified the girls into two distinct categories, the âBetter Educated' and the âMore Genteel'. Mayhew found himself drawn to the âBetter Educated' girls, who were plainly dressed, came from middle-class homes and had âa lady's education'. The âMore Genteel' prostitutes dressed in high fashion. One thing both categories of girls had in common was their abandoned state. They were former milliners or dressmakers from the West End who had fallen into prostitution after being seduced and abandoned by clerks or shop assistants or gentlemen of the town. Others were former servants who had lost their jobs after being seduced, or worse, by the gentlemen of the house or fellow servants.

A considerable number had come up to London from the provinces with young men who subsequently abandoned them, or were decoyed to London by pimps in the age-old fashion. Again, as in previous generations, some girls had arrived in London looking for work and resorted to prostitution when the going got rough, while others were on the run from unhappy families and sexual abuse. There were also âseclusives' down on their luck, having been abandoned by their former lovers, and a number of French, Belgian and German girls. Mayhew admitted that:

They present a stunning spectacle, walking the streets in black silk cloaks or light grey mantles, many with silk paletots [coats] and wide skirts, extended by an ample crinoline, looking almost like a pyramid, with the apex terminating at the black or white satin bonnet, trimmed with waving ribbons and gay flowers. Some have cheeks red with rouge, and here and there are women radiant with health. Many look cold and heartless; others have âan interesting appearance'.

31