The Sexual History of London (17 page)

Read The Sexual History of London Online

Authors: Catharine Arnold

Although there is more than a touch of anti-Semitism in Hogarth's Jewish merchant, Jewish punters were well regarded by prostitutes. The Sephardic Jews whose predecessors had arrived in England under Oliver Cromwell in 1653 were a familiar sight in the purlieus of Drury Lane and Covent Garden. By 1736, they were frequenting the whorehouses at the Garden three or four times a week, particularly on Sundays, with âupright gait, morose speech and pretty smooth Counternance'. Completely Anglicized, they were every bit as good as their gentile counterparts at foppery and lechery, except on Shabbos. But by sundown on Saturday night they were out there spending their money on drinking and loose living. Jews were generally popular among the whores, as they were good spenders and enthusiastic lechers but rarely heavy drinkers. They were also kind and courteous to women and not given to drunken brutality.

As one might expect, there were also Jewish bawds, such as Rose Marks, who, in a textbook example of

chutzpah

, pleaded poverty when charged with keeping a magnificently successful disorderly house at Duke's Place, St James's, and a Mrs Gould, who opened a bagnio in Bow Street in 1742, moving up to much better premises at Russell Street in 1745 which became a well-appointed seraglio with a quiet but distinguished clientele, mainly Jewish, consisting of merchants, bankers and brokers, who would come to her house on Saturday evenings and stay over until Monday mornings.

46

In this quiet, well-disciplined, well-appointed brothel, ârespectable gentlemen' could escape from âthe Noise and Stresses of the Exchange'. Even the girls were well behaved. There was no employment here for any girl who was âaddicted to intoxication or who used any bad language'.

47

A reference to Mrs Gould as âwaddling' suggests that success agreed with her, and by 1779 she seems to have retired with a handsome fortune. Fanny Hill, meanwhile, briefly becomes a Marylebone mistress, having been taken in by the arrogant but handsome Mr H, a middle-aged gentleman.

By Plate 3, Moll has gone downmarket. Having deceived her wealthy Jewish patron, she has been demoted to the position of a common prostitute and is living in a dingy garret in the Garden. Tankards on the floor show that she is drinking heavily, and the medicine bottles and black patches on her face indicate that her syphilis has grown more advanced; her maid's nose is eaten up with lesions. Moll's âsign', a witch's hat and a broom, appear on the wall above her bed, as does a picture of MacHeath, the popular anti-hero from

The Beggar's Opera

, a symbol of lawlessness. But Moll still smiles on, staring out at us, unaware of the fact that she is about to be disturbed by a visitation from the forces of law and order in the form of Sir John Gonson, a Justice of the Peace and scourge of prostitutes, who has arrived with a deputation of men to arrest her.

The doomed Moll Hackabout, from Hogarth's

The Harlot's Progress,

about to be arrested by a magistrate (1732).

Meanwhile, her literary counterpart, Fanny Hill, is in trouble, too. But not for long. Flung off by her lover after he found her having sex with a servant boy (Fanny's response to finding Mr H

en flagrante

with the maid), she is taken in by the kindly Mrs Cole, a sympathetic bawd who runs a successful operation fronted by a dress shop. When the house is eventually raided, Fanny escapes into the night, unlike poor Moll, who is next seen, in Plate 4, as a prisoner at Bridewell, beating hemp. The change in Moll's circumstances is illustrated by the discrepancy between her appearance, in her fine silks, and the cheerless prison. Meanwhile, Moll's maid, nothing if not resourceful, is attempting to capture the attention of their jailer with a sly wink and a tweak of her garter.

By Plate 5, Moll is back in her garret in the Garden, and dying of syphilis, indicated by the shroud-like blankets which swathe her body to âsweat' her. Two doctors are arguing about the effectiveness of their cures, while ignoring her evident distress, and her landlady is going through Moll's trunk stealing her clothes, her witch's hat, her mask and her high heels. By the fire sits a hapless victim of all this: Moll's son, who seems doomed to enter the world of vice and crime.

Children were the innocent victims of prostitution, as is evident from this account of Mary David, born in Hertfordshire. Mary's father died when she was a child, and her mother remarried a poor man. Mary was sent to London as a servant, and worked for two years for a family in Berkeley Square. The footman, although he was already married, seduced her under promise of marriage. She lost her place when she became pregnant. The footman helped her with the child at first, but then she took a place as a wet-nurse and put her own child out to nurse with a woman in Tottenham Court Road. The child she nursed was weaned, her milk dried up and she went to live in the house in Tottenham Court Road. The landlady was very civil, and allowed her to get into debt. Then, one night between eleven and twelve, her landlady came upstairs, âwith manners totally changed, and swore with the grossest abuse, that she would turn her into the street, child and all, unless she brought her some pay'. When Mary asked how she could possibly do that, the landlady replied that âgirls with worse faces than she often picked up a great deal'.

Mary now discovered that one other young lodger there was a kept mistress, and the house was, in fact, âthough in a very private way, a bad house'. Mary took to prostitution, âdriven out in bitter anguish', and eventually found poor friends who took her in. She gave up her child to the parish workhouse, and returned to her mother, in the country. But then she found, âto her inescapable grief', that she was pregnant again, âfrom the sad effects of the prostitution'. Her first child was now dead; the parish had refused to take it from the parish nurse and it had died with a black eye, a broken collarbone and whooping-cough. Mary managed to persuade the Foundling Hospital to take her second child, and from this her story emerges. And, since that story was not known in the country, she planned to return there after she had sold her milk in London.

48

Mary's subsequent fate is unknown, but, given her circumstances, likely to have been an unhappy one.

By Plate 6, the final, black frame of Hogarth's sad story, Moll Hackabout is dead, and her fellow prostitutes are crowding around her coffin. The cautionary tale of Moll's short life is unheeded by the girls taking the opportunity to ply their trade. The parson, staring into space, is slipping his hand beneath the skirt of Moll's friend, while spilling his drink â a symbol of premature ejaculation â watched with resignation by Moll's former maid. Moll's friend gazes out of the picture with half-closed eyes and a faint smile on her lips, an expression reminiscent of Moll's in Plate 3. The cycle of innocence corrupted, sex, decay and death will continue unabated.

49

Fanny, meanwhile, survives to inherit a house in the country and is reunited with her first love.

Fanny Hill

is the Harlot as Heroine, an Enlightenment fantasy, with Fanny inhabiting a benevolent universe free of drunkenness and crime, almost entirely run by women, and where sex takes place in safe, indoor environments, and is a vice, more or less, of the middle and upper ranks of society.

50

Comparing Hogarth and Cleland, it is obvious which version of fallen women was more accurate, and yet

Fanny Hill

is a wonderful piece of escapism, a classic of erotic fiction written by an author who appreciated the possibility of sexual enjoyment for women, although his graphic depictions of young men and detailed descriptions of their organs of generation suggest, at least to this reader, that his interests lay elsewhere.

Moll's life ended unhappily; so did that of Mother Needham, who was arrested in March 1731 on Sir John Gonson's orders, and sentenced to the pillory for her complicity in the rape by Colonel Charteris of the servant Anne Bond, having âfrightened her into Compliance with his filthy Desires' by holding a pistol to her head.

51

Thanks to her friends in high places, Needham was permitted to lie face down on the pillory, which would protect her face. According to the

Daily Courant

, âat first she received little Resentment from the Populace, by reason of the great Guard of Constables that surrounded her; but near the latter End of her Time she was pelted in an unmerciful manner'. According to the

Daily Advertiser

, ânotwithstanding the diligence of the Beadles and a number of Persons who had been paid to protect her she was so severely pelted by the Mob that her life was despaired of'. Several sources claim that she died of her injuries at the scene. But she appears to have been taken down, and committed to Newgate, where she died shortly afterwards.

As for Charteris, he stood trial for rape. The court was told that Anne Bond, who was unemployed, was sitting at the door of her lodgings one day when a woman appeared and offered her a job working for Charteris. The moment she took up her position, he laid siege to her. At seven o'clock one morning, âthe Colonel rang a Bell and bid the Clerk of the Kitchen call the Lancashire Bitch into the Dining Room'. Charteris locked the door, threw her on the couch, gagged her with his nightcap and raped her. When she threatened to tell her friends, he horse-whipped her and took away her clothes and money.

Charteris's rich and powerful friends filled the court to hear him sentenced to death for rape â but he spent less than a month in Newgate and received a royal pardon. Charteris had made himself immune to prosecution by cultivating friendships with some of the most powerful men in the land, including the Duke of Wharton (his own cousin) and the Prime Minister, Robert Walpole.

52

But he was not immune to mob justice. After he was released from Newgate, a crowd set upon him, and, after yet another girl had been rescued from his house, in this instance by her sister, the neighbours stormed his house, bearing âStones, Brickbats, and other such vulgar Ammunition'.

53

When Charteris died of venereal disease in 1731, a jeering mob wrenched the lid off his coffin, threw dead dogs and cats into it and attempted to mutilate his body.

Covent Garden Piazza was indeed âthat great square of Venus', with a floating population of prostitutes offering a plethora of sexual possibilities to the voracious punters. While this chapter has concentrated on the mainstream erotic tastes, let us turn now to the more recondite, even bizarre activities that were on offer in eighteenth-century London.

âWhen Sodomites were so impudent to ply on th'Exchange

And by Daylight the Piazza of Covent Garden to rangeâ¦'

When the actor David Garrick asked Samuel Johnson what he considered to be the two most important things in life, Johnson replied: âDrinking and fucking!' Many Londoners would have agreed with him. Sexuality takes many different forms, however, and London in the eighteenth century had much to offer those with more recherché tastes. In this chapter, we'll investigate such phenomena as the âSodomitical clubs', the flagellation brothels, lesbianism, auto-erotic asphyxiation and last but not least the notorious Hellfire Club. Let us turn first to the âmolly houses', sex clubs for homosexuals from all social backgrounds, but particularly popular with effeminate men or âmollies'.

In May 1726 the

London Journal

carried an account of twenty âSodomitical clubs' in which patrons made their assignations âand then withdrew into some dark Corners to perpetrate their odious Wickedness',

1

including molly houses such as the Talbot Inn in the Strand, the Fountain in the Strand and the Three Potters in Cripplegate Without. Meanwhile, the male proprietor of the male brothel in Camomile Street, Bishopsgate, went under the splendidly camp pseudonym of âCountess of Camomile'.

The most famous molly house was undoubtedly âMother Clap's' in Holborn, which had beds in every room and catered for âthirty to forty Chaps every night' and even more on Sundays, the most popular night of the week for homosexual assignations. Mother Clap (her name appears to be a reference to the pox) was a tolerant old bawd, quite prepared to overhear her patrons âtalk all manner of gross and vile obscenity and be wonderfully pleased with it'.

2

When Mother Clap's was raided, in 1726, and its patrons put on trial, one eyewitness described seeing between forty and fifty men making love to one another, âcalling one another “my dear” and hugging, kissing and tickling each other as if they were a mixture of wanton males and females, and assuming effeminate voices and airs'; they indulged in dancing and making curtsies and

telling each other that they ought to be whipped for not coming to school more frequently. Some were completely rigged in gowns, petticoats, headcloths, fine laced shoes, furbelowed scarves, and masks; some had riding hoods; some were dressed like milkmaids, others like shepherdesses with green hats, waistcoats, and petticoats; and others had their faces patched and painted and wore very extensive hoop petticoats, which had been very lately introduced.

The patrons sat on one another's laps, kissing in a lewd manner and using their hands indecently; after an interval of toying and playing,

3

they would repair to a back room or âchapel' for sex or âmarriage'. When they emerged, they would regale their friends with full details of their âwedding night', and âbrag, in plain terms, of what they had been doing'.

4

At the Fountain in Russell Square, cross-dressers even enacted childbirth scenes, where one molly would deliver a doll. According to Ned Ward, a chronicler of London low life, said doll would be âChristened and the Holy Sacrament of Baptism impudently Prophan'd'. Ward, a tabloid moralist, disapproved of the mollies, condemning them as so totally destitute of all masculine attributes that they preferred to behave as women. They adopted all the small vanities natural to the feminine sex to such an extent that âthey will try to speak, walk, chatter, shriek and scold as women do, aping them as well in other respects'.

5

On occasion, the mollies, or rent boys, lost out: one young man, Edward Courtney, told a magistrates' court that he had been prevailed upon to have sex with a country gentleman at the Royal Oak in Pall Mall, and was told that he would be paid âhandsomely', only to discover that âhe stayed all night but in the morning he gave me no more than a sixpence!'

6

Female prostitutes faced a sliding scale of punishments when apprehended, determined by their class and the social standing of their punters, ranging from a fine to a prison sentence. The stakes were considerably higher for homosexuals, punters and renters alike, and the punishments more severe. Young male prostitutes, or âcatamites', might have cruised the Royal Exchange, picking up rich merchants, but the consequences of arrest and prosecution were far worse than they were for women. Buggery was still illegal, a capital offence which theoretically carried a death sentence if penetration could be proved. While most judges were reluctant to hang âsodomites', convicted homosexuals faced heavy prison sentences, with the act itself being classified as a form of common assault, and being âouted' could ruin a man's reputation.

In 1707, there was a great scandal when a âSodomites' Club' in the City was raided. Forty men who frequented the alleys around the Royal Exchange were arrested, including Jacob Ecclestone, a merchant, who later committed suicide in Newgate; a draper, William Grant, who hanged himself in the same prison; a Mr Jermain, curate of St Dunstan's-in-the-East, who slashed his throat with a razor, and a Mr Bearden who killed himself in the same fashion.

7

In 1726, the Societies for the Reformation of Manners closed down over twenty molly houses, including Mother Clap's. The enlightened patroness found herself in the pillory, and later died of her injuries, just like her fellow bawd Mother Needham. Several of her clients were executed.

Public tolerance of âsodomites' did not improve over the years. In October 1764, the

Public Advertiser

reported that âA bugger aged sixty was put in the Cheapside Pillory. The Mob tore off his clothes, pelted him with Filth, whipt him almost to Death. He was naked and covered with Dung. When the Hour was up he was carried almost unconscious back to Newgate.'

8

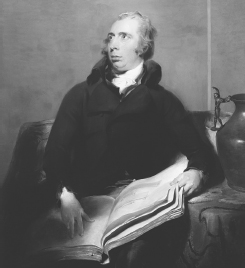

Class and wealth proved no defence against homophobia as is illustrated by the sad fate of Sir Richard Payne Knight (1751â1824), MP for Leominster, connoisseur and antiquarian. From being a backbench MP in a sleepy rural constituency, Knight was reviled as a dangerous subversive when his book on classical antiquities appeared in 1786; hatred and disdain were heaped upon him and some of his best friends, including Horace Walpole, disowned him.

Richard Payne Knight

c.

1793. His

â

Discourse on the Worship of Priapus 'caused a scandal.

Knight's early life gave no indication of this sensational destiny. He was born in Herefordshire, a sickly child who attended neither public school nor university. Knight's family were philistine Tory landowners who distrusted his bookish tendencies, and, years later, Knight admitted that his unhappy childhood and feelings of abandonment might have been the cause of the âungovern'd passions' which led him astray. Although Knight never confided the exact nature of these passions, his choice of subject matter and that he never married provide a clue. This, and the fact that he devoted his twenties to an extended Grand Tour, spending months in Italy in the company of other young men, excavating the Roman remains at Herculaneum which had yielded up a treasure of erotic imagery. Accompanying Knight was his closest friend, John Robert Cozens, a gifted young artist. Cozens, like Knight, was a delicate young man, with a history of mental and physical illness, but the two appeared firm friends until, in the course of one trip, they reached Naples. There, for reasons that have never been disclosed, Knight and Cozens parted for ever, and Cozens suffered a mental breakdown. Supported by the writer William Beckford, Cozens returned to England and was diagnosed with incurable madness by Dr Thomas Monro, medical director of Bedlam. Knight never saw his friend again, but, until Cozens's death in 1799, he paid for his medical care.

Knight, meanwhile, returned to London and fell under the spell of Pierre François Hugues, the

soi-disant

Baron d'Hancarville (1719â1805). A decadent drifter, always in debt, often in prison, d'Hancarville charmed everyone who came in contact with him, winning reluctant admiration from all with his deft combination of the forbidden and the exotic.

9

The shrewd and manipulative d'Hancarville swiftly made himself the object of Knight's âungovern'd passions', paving the way for a scandal which would destroy Knight's career. D'Hancarville was a pornographer who somehow managed to obtain over 700 vases for the envoy Sir William Hamilton, but he could be a deadly ally. One colleague, Winckelmann, was murdered in Vienna. D'Hancarville himself was expelled from Naples for publishing pornographic pictures; in 1769 he managed to make a killing by producing cheaper versions.

D'Hancarville published his own book in 1785. This purported to be a study of the arts of Ancient Greece but was in effect a volume of pornography devoted to the worship of Priapus, depicting couples in a variety of sexual positions under the benevolent gaze of the said deity. In one illustration the happy couple are even depicted âharvesting' Priapus's seed.

10

This inspired Knight to go into print on his own account, and in 1786 he published his

Account of the Remains of the Worship of Priapus

, a scholarly account of his findings in Italy, which also included a dissertation, âDiscourse on the Worship of Priapus'. At first glance, this seems little more than the usual exercise in dilettantism by a learned gentleman who has been on his Grand Tour and seeks recognition in print. The publication's ostensible purpose was to serve as a back-up to a colleague's

Account of the Remains of the Worship of Priapus lately existing at Isernia, in the Kingdom of Naples

, which also sounds deadly dull. However, it was the illustrations which really gave the game away: two dozen sexually explicit black and white images among the 217 quarto pages, culminating in a scene where a satyr is depicted having sex with a goat. As if this was not enough, Knight's innocent tone of âenlightened paganism', in the course of which he argued that sex was a legitimate form of worship and that the crucifix itself, as worshipped by Christians, was a phallic symbol, was taken as evidence of profound anti-clericalism. Although Knight attempted to limit any damage to his reputation by making his book a subscription-only publication, limited to learned gentlemen, news of this sensational tome soon leaked out. Unlike d'Hancarville, a professional pornographer who had absolutely nothing to lose, Knight suffered utter vilification. At one stroke this gentle, learned backbencher was transformed into a monster of depravity. Knight retreated to his country pile a dejected figure, and never lived down the shame. He was not to know that his book, republished in the nineteenth century, would become one of the most popular works of Victorian homosexual pornography. Whether this information would have been of any consolation to him is a matter for conjecture.

11

While Knight was condemned for his learned treatise on male sexuality, a greater degree of tolerance was extended towards one of the most celebrated and curious cases of male to female cross-dressing, that of Chevalier d'Eon de Beaumont (1728â1810). The Chevalier came to England in 1752 in connection with preliminary talks leading to the Treaty of Versailles. He first attracted attention owing to a number of plots attempting to return him forcibly to France. The Chevalier received sympathetic press coverage, which reflected favourably on the relative freedom of England compared with France. At some point during the 1760s, the Chevalier began to appear in public in women's clothes. The rumour was circulated that âhe' had been brought up as a boy, and for political reasons could only now return to his true gender. Reasons for his decision to adopt female dress were legion: some even suggested that he was ordered to do so by Louis XVI, and that he had completed several spying missions for France while disguised as a woman. He did keep press cuttings about cross-dressing, hermaphrodites and related issues, so the topic was obviously very important to him.

The Chevalier's decision to dress as a woman prompted a frenzy of press speculation as to his true gender. The

Morning Post

pledged £200,000 to whoever could settle the argument and the debate raged as to whether he was âa man, an hermaphrodite or any other animal'. Legal disputes over gambling on the issue led to a court case, Hayes

v

. Jaques (1777), in which two doctors testified that the Chevalier was a woman. One claimed that he had treated her for âwomen's disorders', while the other stated that she had made amorous suggestions to him. The court ruled that he was a woman, and the Chevalier signed an affidavit swearing that he had no interest in the bets taken out on him. Press speculation did not however subside: an article appeared in the

Morning Herald and Daily Advertiser

stating that he had always been a woman and concluding that âthe visitation of M. D'Eon to this country in the attire of the feminine, it is hoped will operate so forcibly as to induce such ladies who have usurped a right to wearing breeches, to leave them off'.