The Setting Sun (2 page)

Authors: Bart Moore-Gilbert

The housemaster and his wife are flushed and breathing heavily. Once the boy came into his parents’ bedroom and found them like that. The boy dismisses the thought instantaneously. Everyone knows that this couple doesn’t have sex. Otherwise they’d have children themselves, wouldn’t they, instead of looking after other people’s? Still, the Colonel seems strangely embarrassed, his wary left eye more narrowed than usual, as though training his other one on a particularly elusive target

.

‘Come and sit down.’

The Colonel motions him to an upright chair, before pulling up another for himself. The boy is agonisingly aware that their knees are almost touching. He sits rigidly, afraid to breathe in case they do. The Colonel glances at his wife, perhaps hoping she’ll speak first; but she continues to study the engraving on Oswald’s collar, as if she’s seeing it for the first time. The dog makes to jump down to welcome the visitor, but she restrains him and he begins to whine. With a sigh of frustration, the Colonel turns back to the boy

.

‘The thing is …’ he ventures. He scowls again at Oswald’s protesting yap

.

His wife blushes and places one beringed hand over the dog’s mouth.

‘The thing is … thing is …’

The boy stares. His housemaster is supposed to have been among the first English contingents ashore on D-Day; but now his hands are trembling. Purpling, the Colonel squints beseechingly, before cocking himself like a gun

.

‘I’m very sorry to have to tell you your father’s been killed in a plane crash.’

For a moment the boy’s simply nonplussed. Why’s the Colonel saying this? He knows his father is a brilliant pilot. He’s flown innumerable anti-poaching missions. Then there’s a blood-chilling wail. At first he thinks it’s the Colonel, but his housemaster is gazing at him, aghast, lips pursed again. Oswald buries his nose in his mistress’s lap, ears flopping over his eyes. It’s as if the boy is shaking to bits. Fluid leaks everywhere, tears and snot and saliva, from his eyes, his nose, his mouth. It goes on so long that he starts to feel like he’s drowning. His chest is red-hot, his throat raw. As the tears boil in his eyes, the housemaster’s wife changes shape, bulging and shrinking, like in a crazy fairground mirror, until she eventually pushes Oswald off her lap and waddles forward, tugging a hanky from her pocket. When the boy doesn’t take it, she dabs clumsily at his face, holding herself apart as though fearful she’ll be splashed. The Colonel, too, is on his feet now, performing an agonised minuet

.

‘We’re so very sorry.’

A look passes between the housemaster and his wife, who retreats through the door leading to their private rooms. Courage recovered, Oswald jumps playfully at the visitor

.

‘Where’s my mum?’ the boy stammers, feebly fending the dog off. He’s used a word which is banned among his schoolmates and some reflex makes him wonder if it’s been noticed. His housemaster looks down unhappily

.

‘Apparently there’s no telephone at the chalet. We’re trying to contact her through an old boy who lives in Lausanne.’

He can’t take it in. As the sobs break out again, the Colonel’s wife returns, bearing a caramel éclair on a white plate. Condensation sweats on the icing. She presents it to the boy formally, as if he’s won a prize. Oswald leaps prodigiously. She just manages to whisk the éclair out of reach, catching the icing clumsily under her thumb

.

‘You bad thing, it’s not for you,’ she admonishes indulgently

.

The visitor gazes dumbly at the plate in his lap, cold through his pyjama bottoms. The glazing has buckled and cream oozes out. The dog is frenzied with disappointment

.

‘Your aunt phoned the headmaster from Nairobi,’ his housemaster announces. ‘She thought it best you were told straight away. We don’t know how long it’ll take to get through to your mother.’

‘And Ames?’

His older brother is in one of the senior houses, a mile away

.

‘You can see him in the morning. I’ve spoken with Mr Tring. We think it’s too late now.’

The boy feels helpless. He knows that if it isn’t a lie, it’s an absurd mistake. But he doesn’t know how to challenge these adults. He just wants to get away. He’s thankful when the Colonel eventually bends stiffly, palms on knees, like an umpire with a tricky adjudication to make

.

‘Do you think you’d better go back to bed?’

He in turn seems grateful when the boy nods. His wife coughs asthmatically. She looks like she wants to hug him but doesn’t know how. The boy is strangely relieved

.

‘Are you sure you don’t want the éclair?’ she pleads. ‘It’s from Amps.’

The boy’s spent many a breaktime gazing covetously at the pastries in the grocer’s in the village square, wondering whether it’s worth the risk of expulsion to steal one. He shakes his head

.

‘I’ll just pop it back in the fridge, then,’ his hostess responds, taking the plate

.

‘I’ll fetch Wilson,’ the Colonel says nervously

.

The boy gets up slowly and follows. His head is spinning, so that only when his housemaster calls from the passage does he register that Oswald’s pinioned his leg. Before he can react, the dog has ejaculated

.

‘See you in the morning, then,’ the Colonel says in a hollow voice

.

Oswald barks appreciatively. The boy’s afraid he’ll start crying again in front of Wilson. If he can just hold out until he gets back to bed. But he feels so leaden that he can barely lift his feet. Wilson takes him by the arm again

.

‘I’m sorry, Nigger,’ he mutters

.

The boy senses the prefect casting for something else to say, but there’s only the creak of the interminable stairs. Through a window, a sliver of pewter moon is frozen in its tracks above the bell tower of St Peter’s church. On the landing outside the dormitory, Wilson pauses

.

‘I hear you looked after yourself against Congleton the other day. Good man,’ he mutters encouragingly

.

The boy slithers back between the frosty sheets. Everyone else is fast asleep. He wants to cry again. But it’s as if, during the short time in the Colonel’s study, he’s expressed every drop of water in him. If he starts sobbing, blood will run down his face. The cold scorches his raw lungs. One calf of his pyjamas is damp, but now his brain is working again and he barely notices. What is it, not to have a father? Does this mean no more safaris like the one to the Ugalla River basin the previous Easter, just the two of them, camping under the stars and eating fire-burnt sausages, chalking stumps on the towering anthills? But his father wrote to him only ten days ago, promising tickets for Peter Parfitt and Co. at Lord’s when he comes on leave in June. He knows how disappointed the boy was to have missed out when the MCC came to Dar es Salaam because of cramming for his entrance exams. Not even the scorecard, signed by all the tourists, had consoled him. Promise. The boy rolls the word round and round his mouth. Tunney recovered, didn’t he? So it will be alright. It will. His father

will

come and the whole family go to Lord’s and they’ll talk about Kimwaga and the dogs and the boy’s trip home later in the summer

.

CHAPTER 1

The Father I Did Not Know

One midsummer afternoon, forty-three years after that terrible night, I’m at the computer. Five o’clock. I’m expected in the pub soon, but I just have time to check my emails. On Friday afternoons, nothing much comes in except offers to enhance my breasts or invitations to share the booty of some recently deceased dictator. Hurrying to purge the dross, I almost delete the message from an Indian university. This time it’s not a request for a reference or information about an author. A colleague is researching the nationalist movement during the 1940s in the Mumbai archives. ‘One finds several references to the significant role of a senior police officer named Moore Gilbert.’ What? A hot flush pulses over me. It’s not me but my long-dead father he’s interested in. I can hardly believe my eyes. ‘He had been especially brought to Satara District to deal with the powerful political agitation then going on. This officer had the distinction of having successfully suppressed the revolt of the Hoor tribes in the Sindh province (Pakistan).’ Do I have any family papers which might shed light on those events?

It’s a while before the ringing in my ears dies down. This is the first independent reminder in ages that I once had a father; that the man who castled me so often on his shoulders, found me a porcupine for a pet, taught me football, was a real person. Yet his influence still pervades so much of my life. Even the fact I was writing a lecture about African autobiography when the email arrived can probably be traced back to his accident, and the consequent trauma of expulsion from my childhood paradise. It wasn’t just losing my father, but

Kimwaga, my beloved minder, the exotic pets and wildlife – and Tanganyika, too, its peoples and landscapes – everything that constituted Self and Home. Well into my thirties, I continued to consider myself an exile here in the UK. Those distant events – and my difficulty in coming to terms with them – underlie the unlikely transformation of a sports-mad, animal-obsessed, white African kid who wanted to be a game ranger like his father into what I am today, a professor of Postcolonial Studies at London University. These days I specialise less than I used to in colonial literature, and more in the literatures in English which have emerged from the formerly colonised nations, especially autobiography.

I reread Professor Bhosle’s message several times, trembling with excitement but also a little anxious. The email opens up dimensions of my father’s life I know little or nothing about. I knew he worked in the Indian Police before I was born, but this is the first I’ve heard that he’d been in what later became Pakistan. Or that he was involved in counter-insurgency. I’ve always had difficulty imagining my father as a policeman. He seemed most himself in the informal setting of safari life, clothes dishevelled, sometimes not shaving for days. So why did he join the Indian Police, with its rigid hierarchies and complex protocols? My paternal grandfather was in the colonial agricultural service. But there’s a world of difference between tropical crop research and imperial law and order. My father would’ve spent school holidays in places like Nigeria and Trinidad. Perhaps that gave him a yen to work somewhere in the empire. That and his love of adventure, wild nature and sport, must have made the IP a far more appealing prospect than some industrial enterprise or life assurance office in England. Still.

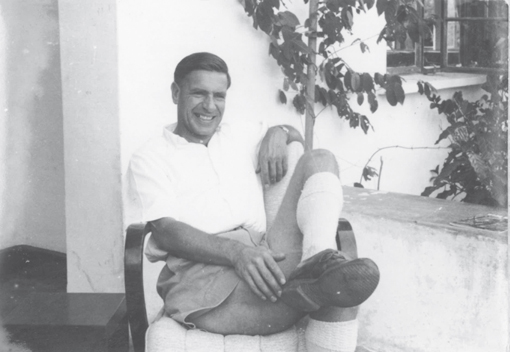

My gaze swivels to the bookshelf, where a black-and-white photo of my childhood hero stares back with a half-smile, as if he’s about to play one of his practical jokes. I feel an aftershock of the avalanche of grief and yearning which engulfed my early adolescence. Taken a few months before he died, it shows a handsome man in his mid-forties, with the strong nose I’ve inherited, a hint of heaviness settling round dark jowls, a second line starting to score his brow and wide-set, mischievous eyes. It’s an out-of-doors face, lean and tanned, a touch of mid-century film-star glamour in the immaculately groomed dark hair. Since overtaking him in age more than a decade ago, I’ve come to think of him as ‘Bill’, the nickname his peers used. It suits much better than his old-fashioned given names. I can’t imagine a Samuel Malcolm wearing that puckish expression.

Bill in 1964, the year before his death

It’s barely dawn and he’s still in pyjamas, at once excited and fearful, racing along the edge of the sandy

shamba

where Kimwaga and the cook grow maize. He’s been strictly forbidden to follow, but the boy can’t help himself, his curiosity’s too strong. Besides, he knows he’s completely safe with his father there. But why are adults so contradictory? His parents have told him a thousand times that if he meets a snake, he must back off slowly, keeping his eyes riveted on it. How can he forget poor Shotty the spaniel, coughing his guts out after the green mamba bit him? Yet here’s his father now, still in his maroon slippers, loping after the cobra through the skinny shadows of the young maize-stalks. One hand grasps the

panga,

a long strip of beaten metal, curved at the bottom and wickedly sharp, which Kimwaga cuts the grass with. The other’s raised defensively, palm forward, at chest height. Yet there’s a half-smile on his father’s face, as if it’s just another game

.

Occasionally the boy glimpses the oily black wriggle in front, hurdling the furrows with surprising speed. On the far side of the

shamba,

Kimwaga and the cook wait, banging saucepans and shouting

‘nyoka, nyoka, hatari,’

as if no one knows that snakes are dangerous. Mainly, though, they’re laughing, the boy can’t understand why

.