The Setting Sun (8 page)

Authors: Bart Moore-Gilbert

It would be too ghoulish to sit there, desperate though I am for a drink. But if I share someone else’s, I’ll have to talk. I shrink back into the crowded pavements, like an injured crab seeking the safety of water. There’s no relief here. Everything jars; sharp-eyed hawkers’ fangy grins, garishly lit shop fronts, screeching music from successive pavement stalls, incomprehensible shouting, combine to create a nightmare fairground. A street-child begs. While guiltily fumbling for change, I accidentally give him my room key, which he returns disdainfully, as if I’m a cheapskate. I come within a hair’s breadth of being knocked down by a cab when I step carelessly off the kerb. In his wing mirror, the driver’s face is a rictus of soundless curses. I feel entirely abandoned.

I must get away from this city of dreadful night. There’s a travel agency. As I plunge in, the young woman adjusts her electric-blue sari with a startled expression. Do I have the mark of Cain?

‘Goa,’ I mutter. ‘I’d like to make a booking.’

‘Yes, sir. Where in Goa?’ Bangles jangle on her wrist, skin the colour of cinnamon, as she waves me to sit. Posters extol the castled glories of Rajasthan.

‘Arjuna Beach.’ It should be really quiet now.

Her X-ray eyes cloud. She shows me brochures of anonymous package hotels. I haven’t even considered what I want. My incoherence makes the woman increasingly uneasy. She speaks into an intercom and a short, perspiring man emerges through the flimsy partition behind. He’s chewing and exhales a nauseous gust of garlic and

brinjal

.

‘Looking for beach action or what?’ he demands, as we go through a more promising list of small guest-houses. ‘Don’t worry about the so-called ban,’ he adds airily. ‘There’ll be lots going on. This one’s very popular with the younger crowd.’

I don’t want to be with the kind of people I’ve just overheard in the Leopold.

‘Are you alright, sir? You look pale.’

Doesn’t everyone look grey in this merciless neon? ‘Just a bit hot,’ I mutter, flicking blankly through another brochure.

‘Why don’t you come back when you’re clearer about what you’re looking for?’ he eventually asks, understandably impatient to get back to his meal.

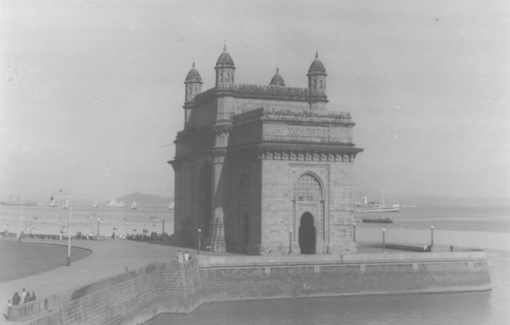

This is better. At the end of a lane leading from Colaba Causeway, I come to the promenade overlooking the Arabian Sea where I sit heavily on a stone bulwark. To my left, I see the darkened Taj Hotel, spectrally impressive beyond the surrounding security barriers, where soldiers are stationed at intervals. ‘Crime Scene. Do Not Cross’, the plastic tape insists. Once finished at the Leopold, the terrorists must have come this way to join their colleagues attacking the Taj. In the eerie street-light it has the look of a ruined monument, windows smoke-scorched, one cupola badly burned. In front of it, the Gateway of India seems to float out of the water. The triumphal triple arch marks the spot where the King-Emperor George V became the first British monarch to visit his Indian possessions, in 1911. It represents everything Bill was defending. Incredible that within less than forty years, all the power

it symbolised had melted away. What part did the Parallel Government play in that process?

The Gateway of India, Bombay 1938

Despite the uncanny atmosphere, the lapping waves and starlight are calming and I start to order my reactions to Shinde. Does anything in what I remember as a child hint that my father was such a man as he describes? Bill certainly had a temper. Yet, despite racking my brains, I can’t remember him being involved in any physical violence during my African childhood – apart from the incident with the cook.

The boy and his father are in canvas chairs, sipping tea from white enamel mugs and scoffing the first sausages of the day. Embers glow in the creamy ash of the previous night’s fire. Above the tents, the dawn clouds are coral still and the bird-song deafening. The boy’s tired. He was up late the previous evening while his father mapped the night sky for him, with binoculars so powerful the boy has to rest them against a tree to stop the shake. And it’s hard to get to sleep in the tent they share. The bush comes alive at night, the air thick with insect noise, the calls of animals looking for a mate or prey, the greedy gulps of frogs. Even the canvas seems to come alive, stretching and contracting like a skin in the night breeze. Every so often he’ll ask his father what’s making a particular sniffle, whimper, hiss or cry. The answer comes immediately, whether it’s a bug, bird or mammal. There’s nothing about the natural world he doesn’t seem to know, what a bull hippo weighs or how long the eggs of weaver birds take to hatch. The bush fits him like a glove. He’s invariably right when instinct tells him they’re close to an animal they can’t yet see. The boy wonders if he’ll ever be master of all this, too

.

A scout approaches, saluting smartly, red beret with brass buffalo-head insignia pulled down to his ears against the early chill. He looks tired after being out all night, having left the previous afternoon to make inquiries amongst the fishermen. One of them’s with him, a very tall, slender man with a small head and dull eyes. He looks unsteady on his legs, perhaps because of his height or because he’s more at home on water

.

‘He says there’s an elephant in a trap, bwana,’ the scout announces. He gives rough co-ordinates and the fisherman answers some questions

.

‘Asante,

Daoudi, thank you

, bwana.

Bring the gun case,’ his father commands, standing up, scratching his stubble and gulping the remainder of his tea

.

The boy goes to fetch the awkward oblong box from the back of the tent where it’s buried under the pile of dirty clothes. The boy loves the freedom of safari, without his mother always telling him to tidy his things. By the time he returns, his father’s organised the team. A driver, Hamisi Sekana, two game scouts – Daoudi and light-skinned Salim – the fisherman and an Ndorobo tracker, a tiny man with a wispy goatee and a right arm so muscular it looks deformed. It’s because he’s been drawing his bow on that side since he was a child, the boy’s father explained on the first day of the trip

.

Soon the Land Rover is bucking off-track towards the low hills overlooking the Ugalla River. They go slowly, because the wet-season grass is growing rapidly, concealing rocks and potholes. The fisherman stands next to Daoudi and the tracker, even more unsteady in the unfamiliar environment of a vehicle, gripping the metal tubing behind the cab, squinting like a ship’s lookout as he scans the fever-trees. Daoudi bangs on the roof occasionally to indicate to the driver to change direction. Hamisi and Salim cradle their weapons, faces impassive. Are they anxious? the boy wonders. He is, but not so much as he’s proud. It’s not like with the spitting cobra, when he was told to stay behind. Now he’s beginning to be treated like a man. Often these days his father asks his opinion on things. Sometimes, he even seems impressed by the answers

.

A gang of warthogs suddenly appears. The mother stares reproachfully over stubby tusks, before high-stepping away; the piglets follow like pinnaces behind a top-heavy mother ship. Once in longer grass, only a rustling current betrays their passage. Along the crest of a hill, a caravan of giraffes proceeds on its stately way, coal-black twigs against the rising sun. The breeze is deliciously cool as it plays through the boy’s blue Aertex shirt. This is heaven, being in the bush, for the first time just him and his father, seeing such sights. He wishes it could be the pattern for all his days. If only there weren’t an elephant in a trap

.

It’s an hour and much hotter before Daoudi bangs and points to two o’clock. The Land Rover pulls over and they all get out. The men check their weapons. The boy holds the gun case, trying to keep his back straight, while his father takes out the double-barrelled .458, a gift from Prince Bernhard. ‘Holland and Holland, Piccadilly’, the gold letters read on the red velvet lining. The boy loves the peppery smell of warm gun-oil which percolates as his father fixes both barrels to the carved stock. They sit over-and-under, not side-by-side like the twelve-bore. The driver’s told to wait with the fisherman. Then they set off in single file, Daoudi and the tracker first, the boy and his father, Salim and Hamisi Sekana bringing up the rear. They walk in silence, dewy grass muffling their footsteps. No one knows where the poachers are and, like buffalo, they’re sometimes bold enough to ambush their pursuers

.

Before long they come to the edge of a gently rising clearing, where the tracker stops. Urgent whispers pass between him and the boy’s father. The boy can see the crushed grass ahead. There’s elephant dung as well. Moist with dew, it looks fresh. But he can tell by the crust it’s a day old, possibly more. They skirt the clearing cautiously, half crouching amongst the low acacia thorn. Halfway across they hear the first scream. The boy goose-pimples. There’s nothing so blood-curdling as the sound of an elephant in pain, not even hyena howls at night, which make him almost want to be young enough still to crawl into his father’s camp bed. The tracker proceeds unhurriedly. Despite his impatience, the boy knows that if they go too quickly, important evidence may be overlooked

.

‘Nne,’

the tracker whispers, holding up four fingers

.

At least they’re not outnumbered, the boy reflects with relief. There’s another anguished trumpet, weaker than the first

.

When they reach the second clearing, the boy wishes for a moment he hadn’t come. Although upwind, the elephant knows they’re there and makes frantic efforts to break free. It’s a young female, tusks ten or fifteen pounds apiece at most. From this distance, the wire’s invisible, but each time she raises her foreleg, the boy glimpses the hideous red grin below the knee. The same haunted look appears on his father’s face as when Shotty the spaniel died

.

‘Stay here with Salim,’ he whispers

.

Once he’s binoculared the surrounding bush, the boy’s father takes out a waxy carton of bullets from his safari jacket, breaks the .458 at the breech and loads a slug in each barrel. He slips a third in his mouth like a dummy before checking his sights. Hamisi Sekana and Daoudi lock their bolts as they slowly advance, one to each side and five yards behind the game ranger. The elephant turns head-on, trunk curling and unfurling as she sips the breeze. Above his pounding heart the boy hears the slap of her ears. Salim faces behind them, cradling his rifle, while his father approaches to about forty yards from the animal. He examines the young elephant again through his field glasses, before signalling Hamisi up beside him

.

The boy sees the black spot between the target’s eyes before he hears the deafening report. There’s a cacophony of protest as every bird within half a mile takes wing. The elephant settles itself a moment before slipping gracefully to its knees, then keels over in slow motion. The trunk’s the last thing to hit the ground, as if it wants one last draw of savannah air. The boy’s awestruck

.

‘Keep your eyes peeled,’ his father calls back, breaking the dead silence which eventually ensues, ‘the mother may still be around.’

The boy looks warily along the inscrutable scrub. But white egrets are already returning to sit amongst the thorn branches, at a respectful distance. If they all suddenly flap up again, it’s time to worry. Yet he’s trembling violently when they advance to examine the animal. Its foreleg’s in terrible condition. In trying to free itself, the elephant has tightened the noose and the wire has cut to the bone. The iron picket to which the noose is attached is hammered down below ground level, protected by barbed wire to prevent the elephant pulling it out. Even had she succeeded, which sometimes happens, the injury would soon have finished her off. Maggots are already swarming in the raw flesh, flies settling on the clouding long-lashed eyes. In its death-throe, the elephant has expelled a last massive pat of dung, which smells sweet as cut meadow

.

The boy’s father gives orders to the scouts and tracker, who disappear towards the east. Hamisi follows behind. With his easy loping stride, which can swallow forty miles in a day, he can afford them a head start

.

‘They’ll probably have heard the shot and be miles away by the time we find their camp.’

‘Why did the mother leave her?’ the boy asks, focused entirely on the elephant

.

‘Maybe they killed her first. This one’s tusks are so small they perhaps couldn’t be bothered, and she wandered over here. Or they’re coming back later to check the trap.’

His father’s subdued for the rest of the day. The episode has cast a shadow over what, for the boy, has been the happiest three weeks he can remember. On returning to camp, the game ranger dispatches more scouts with the driver, to dig up the noose as evidence, hack out the tusks and cut up the carcase to be distributed to the fishermen. It’s a way of keeping them onside, they’re a vital source of information. Late afternoon, they drive the Bedford truck down to the marshes. The fishermen are pleased to see them and even happier with the elephant meat, strips of raw, red, rubbery flesh which turn the boy’s stomach as they slither across the tarpaulin. More and more poachers are coming across from the Congo side, the fishermen complain. They, too, suffer from the trespassers, who often demand food and sometimes take their catches by force

.