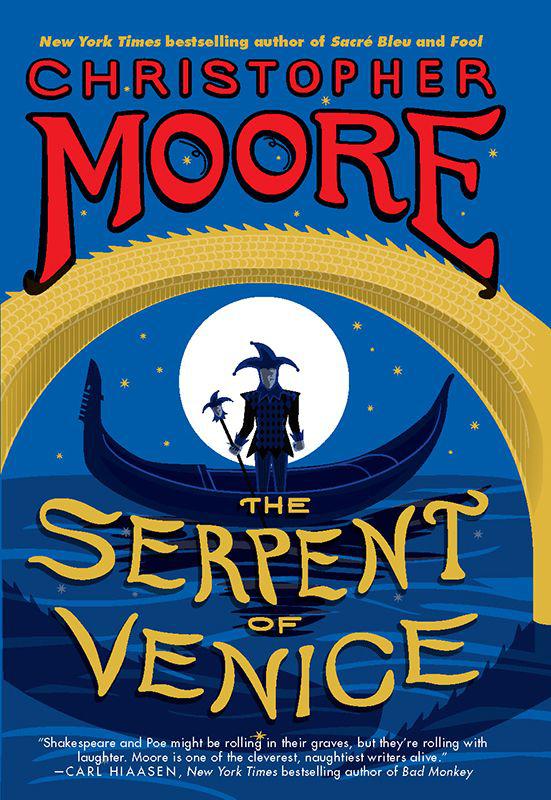

The Serpent of Venice

Read The Serpent of Venice Online

Authors: Christopher Moore

Tags: #Fiction, #Humorous, #Historical, #Mystery & Detective, #General

CONTENTS

Four: How Much for the Monkey?

Nine: Two Thousand Nine Hundred and Ninety-nine Golden Ducats

Ten: Intrigue Beneath the Bawd

Thirteen: Bold and Saucy Wrongs

Sixteen: A Nasty Piece of Work

Act IV: The Green-eyed Monster

Eighteen: Cloak, Dagger, Wimple, and Veil

Nineteen: Well Met in Corsica Once More

Twenty-five: Arise! Black Vengeance!

Twenty-six: Off Jolly Rogering!

Chorus—

a narrator

Antonio—

a Venetian merchant

Brabantio—

a senator of Rome, father of Desdemona and Portia

Iago—

a soldier

Rodrigo—

a gentleman soldier, friend of Iago

Pocket—

a fool

Portia—

a lady, younger daughter of Brabantio, sister to Desdemona

Nerissa—

maid to Portia

Desdemona—

a lady, elder daughter of Brabantio, sister to Portia

Emilia—

wife of Iago, maid to Desdemona

Othello—

a Moor, commanding general of the Venetian military

Shylock—

a Jew, Venetian moneylender, father of Jessica

Jessica—

Shylock’s daughter

Bassanio—

friend of Antonio, suitor to Portia

Lorenzo—

friend of Antonio, suitor to Jessica

Gratiano—

young friend of Antonio, a merchant

Salanio—

young friend of Antonio, a merchant

Salarino

—also a young friend of Antonio, interchangeable with Salanio, may have been born of a typo

Drool—

a fool’s apprentice

Jeff—

a monkey

Cordelia—

a ghost. There’s always a bloody ghost.

T

he stage is a mythical late-thirteenth-century Italy, where independent city-states trade and war with one another. Venice has been at war with Genoa, off and on, for fifty years, over control of the shipping routes to the Orient and the Holy Land.

Venice has been an independent republic for five hundred years, governed by an elected senate of 480 men, who in turn elect a doge, who, advised by a high council of six senators, oversees the senate, the military, and civil appointments. Senators come mostly from Venice’s powerful merchant class, and until recently could be elected, by neighborhood, from any walk of life. But the system that has made Venice the richest and most powerful maritime nation in the world has changed. Recently, privileged senators, interested in passing the legacy of power and wealth to their families, voted to make their elected positions inheritable.

Strangely, although most of the characters are Venetian, everybody speaks English, and with an English accent.

Unless otherwise described, assume conditions to be humid.

Hell and Night must bring this monstrous birth to light.

—Iago,

Othello,

Act I, Scene 3

CHORUS:

INVOCATION

Rise, Muse!

Darkwater sprite,

Bring stirring play

To vision’s light.

Rise, Muse!

On fin and tail

With fang and claw

Rend invention’s veil.

Come, Muse!

’Neath harbored ship,

Under night fisher’s torch,

And sleeping sailors slip.

To Venice, Muse!

Radiant venom convey,

Charge scribe’s driven quill

To story assay.

Of betrayal, grief and war,

Provoke, Muse, your howl

Of love’s laughter lost and

Heinous Fuckery, most foul . . .

T

hey waited at the dock, the three Venetians, for the fool to arrive.

“An hour after sunset, I told him,” said the senator, a bent-backed graybeard in a rich brocade robe befitting his office. “I sent a gondola myself to fetch him.”

“Aye, he’ll be here,” said the soldier, a broad-shouldered, fit brute of forty, in leather and rough linen, full sword and fighting dagger at his belt, black bearded with a scar through his right brow that made him look ever questioning or suspicious. “He thinks himself a connoisseur, and can’t resist the temptation of your wine cellar. And when it is done, we shall have more than Carnival to celebrate.”

“And yet, I feel sad,” said the merchant. A soft-handed, fair-skinned gent who wore a fine, floppy velvet hat, and a gold signet ring the size of a small mouse, with which he sealed agreements. “I know not why.”

They could hear the distant sounds of pipes, drums, and horns from across the lagoon in Venice. Torches bounced on the shoreline near Piazza San Marco. Behind them, the senator’s estate, Villa Belmont, stood dark but for a storm lantern in an upper window, a light by which a gondolier might steer to the private island. Out on the water, fishermen had lit torches, which bobbed like dim, drunken stars against the inky water. Even during Carnival, the city must eat.

The senator put his hand on the merchant’s shoulder. “We perform service to God and state, a relief to conscience and heart, a cleansing that opens a pathway to our designs. Think of the bounteous fortune that will find you, once the rat is removed from the granary.”

“But I quite like his monkey,” said the merchant.

The soldier grinned and scratched his beard to conceal his amusement. “You’ve seen to it that he comes alone?”

“It was a condition of his invitation,” said the senator. “I told him out of good Christian charity all his servants were to be dismissed to attend Carnival, as I assured him I had done with my own.”

“Shrewdly figured,” said the soldier, looking back to the vast, unlit villa. “He’ll think nothing out of order then when he sees no attendants.”

“But monkeys can be terribly hard to catch,” said the merchant.

“Would you forget about the monkey,” growled the soldier.

“I told him that my daughter is terrified of monkeys, could not be in the same room with one.”

“But she isn’t here,” said the merchant.

“The fool doesn’t know that,” said the soldier. “Our brave Montressor will cast his younger daughter as bait, even after having the eldest stolen from the hook by a blackfish.”

“The senator’s loss cuts deep enough without your barbs,” said the merchant. “Do we not pursue the same purpose? Your wit is too mean to be clever, merely crude and cruel.”

“But, sweet Antonio,” said the soldier. “I am at once clever, crude,

and

cruel—all assets to your endeavor. Or would you rather partner with the kindly edge of a more courtly sword?” He laid his hand on the hilt of his sword.

The merchant looked out over the water.

“I thought not,” said the soldier.

“Put on friendly faces, you two.” The senator stepped between them and squinted into the night. “The fool’s boat approaches. There!”

Amid the fishing boats a bright lantern drifted, and slowly broke rank as the gondola moved toward them. In a moment it was gliding into the dock, the gondolier so precise in his handling of the oar that the black boat stopped with its rails only a handsbreadth from the dock. A louvered hatch clacked open and out of the cabin stepped a wiry little man dressed in the black-and-silver motley and mask of a harlequin. By his size, one might have thought him a boy, but the oversize codpiece and the shadow of a beard on his cheek betrayed his years.

“One lantern?” said the harlequin, hopping up onto the dock. “You couldn’t have spared an extra torch or two, Brabantio? It’s dark as night’s own nutsack out here.” He breezed by the soldier and the merchant. “Toadies,” he said, nodding to them. Then he was on his way up the path to the villa, pumping a puppet-headed jester’s scepter as he went. The senator tottered along behind him, holding the lantern high to light their way.

“It’s an auspicious night, Fortunato,” said the senator. “And I sent the servants away before nightfall so—”

“Call me Pocket,” said the fool. “Only the doge calls me Fortunato. Wonder that’s not his nickname for everyone, bloody bung-fingered as he is at cards.”

At the dock, the soldier again laid hand on sword hilt, saying, “By the saints, I would run my blade up through his liver right now, and lift him on it just to watch that arrogant grin wither as he twitched. Oh how I do hate the fool.”