The Secret Life of Uri Geller (16 page)

Read The Secret Life of Uri Geller Online

Authors: Jonathan Margolis

Tags: #The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Cia Masterspy?

Oddly, spoon bending, even though it was happening with increasing regularity and was seemingly coming under his control, was something Uri avoided doing with his friends. But with adults, he was unstoppable. Margaret’s main pastime was drinking coffee and eating cake with her girlfriends. Uri would often accompany her, to the distress of many Tel Aviv café owners. He would be quietly eating a piece of cake when spoons on the café table would start curling up. The waiters would whisk them away, not wanting to give the impression the cafe used bent spoons – or indeed attracted naughty little boys as customers. Margaret would explain to her friends and the staff that such things sometimes happened when Uri was around.

One of Margaret’s Hungarian friends was a younger woman, Shoshana Korn, who was at that time working in a hotel in Tel Aviv. Shoshana, or Juji as she was known, became Uri’s godmother.

‘We were in a café on the corner of Pinsker and Allenby one day when Uri started to play with the spoons,’ Juji recalls. ‘He was five or six, and bent four or five coffee spoons double. ‘I said, “Manci, I hope you have plenty of money to pay the café owner.” Fortunately, the owner was amused. I said, “Uri, you’re going to ruin your mother.” He said, in Hebrew, that it just came to his head how to do this, but his mother wouldn’t let him do it in the house. All the other people were amazed. And as well as being able to do these incredible things, Uri was very smart, too. He’d stop clocks and watches, too, but then he’d always start them again.

‘Another friend of ours, Anush, said to Manci, “You know one day you won’t have to work all night, because he’s going to make a lot of money.” Uri used to spend a lot of time with Anush and her husband, Miklos. I remember her saying you had to hide everything made of metal from Uri, because he’d bend it. Miklos was a handbag maker, and he would sometimes get angry with Uri because he would bend his tools and the clasps he used. But then he’d say, “I don’t know what to do with this Uri. He’s a genius.”’

The final disintegration of the Gellers’ marriage ended Uri’s days as a city street kid. He was moved temporarily, to avoid the chaos of the breakup, to a kibbutz called Hatzor, far to the south of Tel Aviv near Ashdod, that specialized in taking in children from broken homes. Here, they would be lovingly looked after within a settled, nuclear family, perhaps start to mend psychologically, and maybe even develop a taste for the simple, healthy country lifestyle.

A Hungarian-Jewish family, the Shomrons, took Uri in just before he was ten, in 1956, and the family’s son, Eytan, became his close friend. Yet, oddly, he did almost nothing paranormal to try to impress Eytan.

There were odd incidents, nonetheless. Eytan – who saw Uri bend a spoon only when they were both 40 – recalls Uri accurately predicting a crash at the neighbouring air force base.

‘My brother Ilan remembers Uri telling him that an airplane was going to crash tomorrow, and it did,’ says Eytan. Uri, curiously, remembers saying in class one afternoon only that he thought ‘something’ terrible was going to happen, not that it was a crash at the air base, just beyond the wheat fields. ‘I suddenly felt something very powerful in me, almost like a feeling of running out of the classroom. A very short time afterwards, we heard this huge bang. We all ran out of the studying bungalow and across the cornfields we saw smoke and we all started running towards this jet on the end of the runway embedded in the ground and the pilot inside with blood all over his face. It was quite something, the first time in my life that I encountered someone dead or dying. Actually, he survived and months later, he came over to see us and tell us about it.’

One former kibbutz child, however, has a very vivid memory of Uri giving him a brief glimpse of what he could do. Avi Seton, who became a management consultant in Portland, Oregon, was walking with Uri from the dining hall to the swimming pool one day when Uri suddenly said to him, ‘Hey, look what I can do.

‘Uri took off his watch and held it, and the hands just moved without him doing anything. I’m not sure if he was sophisticated enough at ten years old for some kind of sleight of hand to be involved, and I clearly saw them move. For some reason, I got the feeling then and now that it wasn’t something he could really

do

, but rather something that was

happening

to him. But the funny thing was that all I said when I saw this was, “Hey, so what.” I think it was always going to be like that for him when he showed these things to kids. “Hey, that’s good, but you want to see how high I can jump.”’

Eytan Shomron believes all the time they were together back in the mid-50s, Uri was thinking of giving his friend some indication that there was more to him than met the eye. ‘I remember once walking on a dirt road in a field of wheat when Uri asked me, if I had the ability to know where the snakes are hidden in the grass, would it make me feel better. There were a lot of snakes, and they were extremely frightening, but I said, “No, I wouldn’t want to know.” It was such a strange question. Years later, I thought it was an attempt to hint at what he could do, to signal to me that he was sitting on a secret.’

When Uri’s mother remarried and moved to Cyprus with her new husband, Ladislas, a former concert pianist, new vistas opened for the young Geller. He could see his mother was happy for the first time in a long while. He could leave the kibbutz, which he wasn’t keen on. And as Ladislas was quite well off, an end to the family’s poverty seemed within sight. But there were other, more subtle, benefits.

Cyprus was a British colony, so the boy would learn English to near perfection, which would be of huge benefit to his subsequent career. He would also become familiar with American culture. He had an American girlfriend for a while, hung out at the American club, got to love hot dogs, played in a baseball team and very much took on board the idea that the streets in America were paved with gold. At the suggestion of the Greek Cypriot customs man Uri was processed by when he arrived by ship at Larnaca to settle on the island, he even adopted the English (but also Greek) name George, which he used for all the years he was to live there, from the age of 11 to 17.

Uri was developing a yearning to show other adults, independent of his family and more sophisticated than his mother’s coffee shop friends, the strange things he could do. Among the staff at Terra Santa College, his Catholic boarding school outside Nicosia, he would find such adults. Among the more significant of them were Brother Mark and Brother Bernard, both former Navy SEALs and a certain Major Elton, an ex-French Foreign legionnaire who taught maths at the college. These were the kind of people he wanted to show what he could do – if only to be reassured that he wasn’t a freak. (Among other important influences in his life that he met in Cyprus was, of course, the Mossad agent Yoav Shacham, the story of which appears in

Chapter 3

.

Establishing through third parties, preferably unrelated, that Uri Geller had special abilities as a child is crucially important in unravelling his life story. His major critics would one day assert that Geller’s powers mysteriously manifested only in his early 20s, after he happened upon a magicians’ manual with a teenage friend [Shipi] and the two together sensed the makings of a wonderful scam. But it is in Uri’s Cyprus period, from 1957 to 1963, that we begin to encounter strong indications that he was fully formed long before his critics believe. The list of children, teachers and others who attest to having seen and experienced his abilities so early in his life, before he had met Shipi and before he had supposedly learned mental magic from a book is so long, and their memories so precise, that the much-touted argument that Geller invented his ‘powers’ in league with Shipi a decade later starts to look distinctly threadbare – ridiculous, in fact.

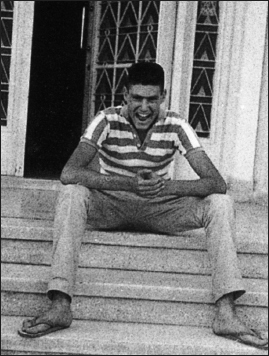

Uri on the steps of Pension Ritz, Nicosia, Cyprus, aged 17, just before his return to Israel.

Cyprus was also, inevitably, the scene for other major influences to come into his life. One of these was sex – his first, and also enjoyable and successful, experiences occurred here. Another was show business. He met theatricals at his stepfather’s motel, a 14-bedroom establishment at 12 Pantheon Street in Nicosia, bearing an ambitious name for a little place: Pension Ritz. The Ritz was frequented by visiting performers working Nicosia’s busy nightlife scene – and Uri developed an affinity with them and their lifestyle. He says he showed some his spoon bending and watch-disturbing abilities, and they were duly impressed.

Another, odder characteristic he evolved was a fascination for the ghoulish. Cyprus was war-torn and dangerous for his entire time there, as an ongoing war between terrorists, both Greek and Turkish, and the British Army was being fought. Uri frequently witnessed dead and mutilated bodies and the aftermath of bombings, all of which had its effect on the psychology of a young boy.

Just a year after Uri arrived on the island, Ladslas died, leaving Uri’s mother alone for the second time. Even so, he still looks on his time on the island as one of the best of his life. For him, it was mostly a time of ranging about on his bike, taking the bus with his beloved fox terrier, Joker, to deserted beaches, swimming, snorkelling and getting to know about girls.

Uri was first sent to board at the American School in Larnaca, where he was not happy, but he quickly picked up English there. His second school, Terra Santa, was in a safe part of Cyprus, in the hills around Nicosia. It was strict, run by monks and had fairly primitive facilities – but provided an education well up to highly demanding, 1950s’ British standards, something that came as a shock to many of the pupils, especially the Americans. Yet Uri was content there almost from the start.

Characteristically, he didn’t show much of his paranormal ability to the other boys there. One contemporary, Ardash Melemendjian, now living in York, remembers only certain little things that happened around the new boy, George Geller. ‘The college was built in an area they called the Acropolis, all stone quarries and caves. We used to go down to these caves. They were quite dangerous, and we were told at school that some boys had got lost and died down there once. One time when we were trying to get out of the deepest caves we got badly lost. We were faced with three ways to go in the pitch black. Someone started to say something and suddenly Uri said “Shhh!” and everyone hushed. He thought for a minute and then say, “This way!” and we went straight on or to the left, whichever the case was, and then we walked a long way before anything happened. But suddenly, we saw a little circle of light, and it got bigger and bigger, and that was the exit. I’m sure the rest of us would have chosen another way. I don’t how he did it.

‘There were other oddities which when you put them together, even back then, just made you wonder what

was

this guy,’ Melemendjian continues. ‘He never once got a puncture on his bike, and yet we used to ride through the same fields, the same thorn hedges. I’d get them all the time, and end up sat on the back of his bike, holding my bike while he was peddling. We’d go to the cinema to see X-rated films. I’d go to buy my ticket and get told, “No! You’re too young! Out!” He’d go to buy his ticket – and would be perfectly all right for him even though we are the same age and looked it.

‘Another thing that we used to take for granted, never give a second thought to – he never revised for anything. You’d find him sat down with a textbook that we were supposed to be studying and he’d have a comic inside it. But when it came to overall results at the end of the term, you could bet your boots that he’d be top.’

Uri also became a basketball star, not just because he was tall and athletic. He had an ability, clearly remembered by Melemendjian, other boys and staff, to move the hoops to help them meet the ball.

‘It looked as if it was vibrating without anybody at all touching it. You could see it move, I believe, a couple of inches when George was shooting at it,’ recalls Andreas Christodoulou, who is still in Nicosia and working as a heating contractor.

One Terra Santa teacher, Joy Philipou, now in retirement in the London suburbs, remembers of Uri: ‘He stood out. You can’t have gifts like that and remain anonymous.’ Of the basketball prowess, she says, ‘He

guided

the ball. He could shoot from almost anywhere. It never, ever missed the basket. Now that is a feat for an 11-year-old. From one end of the court to another, over and over again. I thought it must be my imagination, but several people began to talk about it.

We all saw the ball sway when there was no one near it, or sometimes the post would sway a few inches to the left or the right, whichever way he wanted it for the ball to go in. In truth, it was really scary. There’s been a great deal of talk and argument. People would say, “Ah, no, it’s just a fluke, someone must have pushed it.” But then you’d see it happen over and over again.’

Joy also remembers him pulling off pranks in the classroom. ‘For example,’ she says, ‘he did this clock-moving thing, not just on me but on other teachers. But for me, it took a long, long time before I put two and two together and realized that it was him that was doing it. I wasn’t into the supernatural or anything like that, and I couldn’t make out what it was. But whenever it was my turn to ring the 12 o’clock bell, I would have Uri fidgeting in the class, wanting to get out for lunch.