The Secret Life of Uri Geller (11 page)

Read The Secret Life of Uri Geller Online

Authors: Jonathan Margolis

Tags: #The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Cia Masterspy?

Byrd recounted two other occasions he knew about of Geller apparently working with Israeli intelligence after his arrival in the States. ‘One time, in 1976, Uri called me when he was in New York and said he had had an encounter that evening with someone who said they were from Israel who asked if he would like to do something beneficial for his country. They wanted him at a certain time the next day to concentrate on some latitudes and longitudes, and to think, “Break! Break! Break!” He asked what was there, and this person said that if whatever there was there was to break, or if Uri could interfere with it, it would be good for Israel. He asked me if I thought he should do it, and I said, “I don’t know. Why not? It would be interesting to try and see what happens.”’

What had already happened was that an Air France Airbus had been hijacked by terrorists and given shelter in Idi Amin’s Uganda: 101 passengers and the captain were being held hostage. What was about to happen was that the Israelis went on to mount a daring rescue mission by commandos who flew in on four Hercules aircraft. Benjamin Netanyahu’s older brother, Yonatan, was commander of the elite Israeli army unit on the operation, and was the only Israeli killed on it.

‘Uri called me all excited later on,’ said Byrd, ‘and asked if I’d heard what happened. The successful Israeli rescue raid on Entebbe had taken place, and he was sure the co-ordinates he had been given connected with it in some way.

‘Uri kept saying, “The radar in Entebbe, there must have been radars there. Can you find out if there were radars at these points?”’ I said I’d try. I had contacts with people at the CIA. I called them and asked them could they find out if there were radars at these latitudes and longitudes, as they were roughly on the way from Israel to Uganda, and if they could find out if the radar was really knocked out or not. They called me back and said they didn’t have any information about that. They said the raid as far as we know was conducted underneath the radars anyway and we have no indication that there were radars at those points and whether they were working. But Uri had called me beforehand to tell me about this, and then the raid happened, so I thought that was pretty good.’

Byrd was not suggesting that this conclusively proved that Uri’s psychic ability had knocked out all radar on the 3,520 kilometres between Israel to Uganda, and Geller is – eloquently, perhaps – silent on the matter. But Byrd argued that it did suggest at least that a Mossad agent was in contact with him – and believed he could mind-hack electronics.

A balanced reading of the Entebbe raid and Geller’s part in it is that he was almost certainly drafted in as a slightly peripheral – but easily activated – backup to simply evading the radar stations en route, or avoiding them by some other more conventional method. The most threatening of these radar stations were in Egypt and in Eritrea, where a state-of-the-art Soviet installation was in operation. Andrija Puharich said Uri was asked to block 11 radar stations in total. ‘I can only describe his role as being a shield for Israel like the shield of David in the Bible,’ the physicist said. ‘Whenever there was a problem, he was consulted and would give his ideas and opinion. He would see things that might happen, could possibly happen and so on.’

The mad Idi Amin, Uganda’s despotic ruler, admittedly not the most reliable source, did tell reporters that the Israelis had ‘jammed our radar’, and there was another curious hint about possibly unconventional methods being used on the mission, this one from an Israeli officer briefing the press in Jerusalem after the raiders returned safely from Entebbe.

‘The main problem was to get to the terrorists with the biggest surprise possible,’ the officer told the world’s media. ‘We used several tricks to do that, and once it worked, all the rest was quite simple.’ Uri for his part does not discuss the raid, but has said, ‘Use your imagination. Wouldn’t I have been asked to do things of this nature? Of course I would.’ (Interestingly, Israelis, even those who accept Geller’s abilities are real, usually use the word ‘tricks’ to refer to them. The officer’s press statement could perhaps be seen as a coded tease in this light.)

An unnamed expert on the Entebbe raid told

The Independent

newspaper in 2013 that the Mossad, with British help, had gained details of the specifications of the radar system at Entebbe and therefore knew the precise approach direction that would be blind to Ugandan radar. He hinted interestingly, however, that a Mossad disinformation tactic might have been to let it be thought Uri Geller had been somehow involved in blocking the radar to deflect any suggestion of the British involvement.

Byrd also told the author of another instance of Geller being used by the Mossad. ‘Uri had been secreted out of the USA by the Mossad dressed as an El Al airplane mechanic. In a 747, there is a way from the cargo hold up into the cabin. That way, they got him in and out without going through customs. He told me they took him back to Israel and flew him over some place in Syria two days in a row and said they wanted to know where a particular power plant was from his psychic impressions, and he told them. By gosh, just a day or so after he told me that, they bombed it.’ Russell Targ has said that it is ‘totally believable’ that Uri had been used to help Israel’s June 1981 air strike on the Osirak nuclear reactor site in Iraq, then under construction. (When asked about this alleged mission, Uri was taken aback. ‘I really don’t recall ever telling anything about this to Eldon,’ he said. ‘I wonder if he got it from some other source?’)

It is late 1976 before corroborated evidence emerges of Uri being used operationally by the CIA rather than him being observed by it. For over a year between 1976 and early 1978 he found himself living in Mexico City as a sort of psychic aide to Carmen Romano de Lopez Portillo, known as Muncy, and the glamorous wife of the country’s president, Jose Lopez Portillo.

Uri had been brought to Mexico originally for a TV show. After the show, Muncy, then the first lady-elect, summoned him to her home with a police escort, to meet him. Lopez Portillo’s predecessor, Luis Echeverria, later welcomed Uri at a reception at Los Pinos, the Mexican White House, and Uri immediately felt an affinity with the country. Echeverria’s oil minster, Jorge Diaz Serrano, had a hunch that Uri Geller could help the state oil company, Pemex, locate oil reserves it knew it had, and was anxious to exploit. Lopez Portillo put Serrano’s hunch to the test after he became president in January 1977. And it worked unbelievably well. Although Uri fretted that he had more or less guessed the site from a helicopter, he was spot on.

Geller’s dowsing abilities, his financial mainstay from his mid-30s onwards, had been discovered in England by the chairman of the British mining company Rio Tinto Zinc, Sir Val Duncan, who had seen Uri on TV and invited him to his home in London. Duncan suggested that bending spoons might not always be the best way for him to make use of his talents. He later took Uri to his villa on Majorca aboard the RTZ company jet. There he passed onto Geller his surprising knowledge of dowsing – surprising for a man who had been an ADC to Montgomery during the war, and was now a director of the Bank of England.

Uri with Muncy, the wife of the Mexican President Jose Lopez Portillo.

Geller subsequently did well mineral hunting for RTZ in Africa, and was so successful with his dowsing work for Pemex

,

that he was granted Mexican citizenship. He and Shipi were also flown around with Muncy on private jets and given luxury penthouses complete with pools in the exclusive Zona Rosa to use, along with the plentiful supply of señoritas who were fascinated to meet the handsome young Israelis-about-town. Their main preoccupation was keeping it from Muncy that Uri was seeing many other – and younger – women at the same time as her.

Mexico City’s Soviet embassy, not far from where Uri and Shipi were cavorting, was known to be the nerve centre of the KGB’s spying operations in the USA, a major headache for the Americans. So somebody at the Mexico City CIA station seems to have had the idea of deploying Geller for intelligence work. His seemingly interesting connections with the Mexican establishment, which was a tad too friendly to the Soviets for Washington’s liking, could be worth exploring, too. Uri had meanwhile befriended Roger Sawyer, a former US Army officer and now a consular officer at the US embassy in Mexico, who he and Shipi had met when they were renewing their US visas.

‘He invited me to lunch one day and he said we were going to the President’s house,’ Sawyer says. ‘I was a little bit sceptical, but I thought, “All right, we’ll see where this leads.” So we actually went to the President’s house and we had lunch with the wife of the President of Mexico. And while we were there, the President made an appearance, said “Hello!’ then excused himself because he didn’t have time to stay for lunch.’ Sawyer was fascinated at the level of Mexican society the young Israeli had penetrated, but as he puts it, ‘It was a little bit above my pay grade, so I didn’t try to get involved in those activities because I knew that that wouldn’t end well for me.’

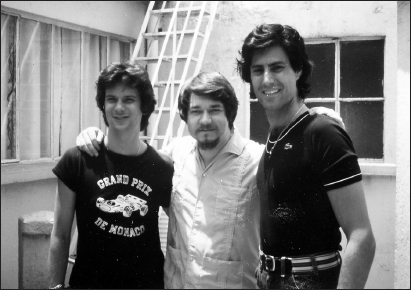

Uri and Shipi with Roger Sawyer, consular officer at the US Embassy in Mexico City.

Soon afterwards, Uri says he got a call from an American identifying himself as Mike. Uri was surprised the man had the phone number of his penthouse but agreed to meet him at a Denny’s chain restaurant in Mexico City. ‘He said, “We know what you did at Stanford Research Institute. I’ve seen the reports. We know you can do certain things with the power of the mind. Can you help us?”’ Uri confirmed that he could indeed do this. So Mike gave him two specific missions, offering, as he had been authorized to, the carrot of helping him and Shipi out with their still slightly tricky visa applications – not that Uri needed much of a carrot.

The first task was to report to Mike the names of the Soviet embassy officials Lopez Portillo and his ministers were seeing, Washington continuing to be concerned about Mexico’s friendliness with the Soviets. The second was more exciting to Uri. ‘Mike explained to me that every ten or 15 days, there was a diplomatic pouch that goes out of the Russian embassy handcuffed to the wrist of one of the KGB agents and with secret floppy disks inside. Mike was also aware that I was able to erase floppy disks.’ (He had previously done just that at Western Kentucky University under the gaze of the physicist Dr Thomas Coohill and word had clearly found its way to the CIA.) Mike then asked Uri Geller to hang around outside the embassy. He even gave him a pair of reflective, rear-viewing sunglasses to wear so he could keep an eye on the front entrance – while apparently looking in the opposite direction – and try to get a feeling for who was coming in and out that might be of interest to the CIA.

It was proposed that Uri, with his Mexican passport in the name of his mother’s distant family, the Freuds, begin to accompany known KGB couriers carrying floppy disks back to Moscow on board Aeromexico flights. His job would be to sit close to the courier for the Mexico City to Paris leg, mentally erasing the disks for the duration of the transatlantic flights and hopping off in Paris, leaving the unsuspecting courier to board the Aeroflot flight to Moscow with the now-useless disks. The problem arose, however, that the KGB agents travelled in first class, and Uri, never shy to discuss finance, asked Mike who was going to pay for his – and the ever-present Shipi’s – fares? Mike came up with the idea that he should drop a hint to the Mexican president that a couple of the rare and special Aeromexico gold cards, only given to Mexico’s elite and allowing limitless free first-class travel to anywhere the airline flew, would be quite handy. In return, Uri would be more than happy to promote Aeromexico by wearing specially made Aeromexico-branded T-shirts around town.

Uri was never told if he had been successful on the first disk-erasing mission, but says it was telling that he was asked to do the same again twice more. If he had been successful, the consternation and recriminations within the KGB when their floppy disks from Mexico City kept turning up in Moscow blank or corrupted can only be imagined. Wiping floppy disks was not the only thing Uri did. ‘I told them about drop-outs and drop-ins in at the Russian Embassy, and Mike also took me out to the desert to test if I could move a drone, a spy model aeroplane, with the power of my mind. I managed to do that too,’ he says.