The Secret Life of Uri Geller (23 page)

Read The Secret Life of Uri Geller Online

Authors: Jonathan Margolis

Tags: #The Secret Life of Uri Geller: Cia Masterspy?

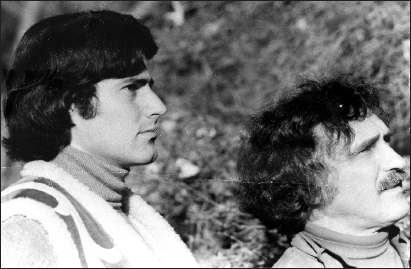

Uri with Dr Andrija Puharich.

The next day, Puharich repeated the telepathy tests with the same success, then asked Uri to concentrate on a pair of bi-metal strip thermometers. Even from across the room, Geller was capable of raising the reading on whichever of the instruments he selected by six to eight degrees.

Thoroughly convinced now that Uri Geller really did possess startling telepathic and psychokinetic powers, Puharich started to interview him about his past, and about his views on what his powers were. Puharich was impressed and surprised by the depth of introspection Geller, considering his basic education, had achieved. The core of Uri’s own beliefs on the subject was that telepathic waves travel faster than light – something, remember, which only quantum physicists were aware was even possible, and even then, not unanimously aware.

If the light speed barrier were overcome, Uri suggested, then we could see into the past and the future, as well as teleport materials instantaneously. He also said he believed that the particles that existed beyond the speed of light were too small to have yet been discovered. On the question of teleportation, he did not discuss his extraordinary incident in the army with the heavy machine-gun parts that had apparently teleported to him in the Negev, but he did tell Puharich that when he broke a ring, it often lost weight, and how when he snapped a jewellery chain, a link was frequently found to have vanished.

Uri also speculated, Puharich reported, on what the source of his powers might be. One idea was that he had inherited them by some genetic fluke from a previous human civilization, to whom they were commonplace. A second theory of his was similar, but proposed that his ancestors had interbred with extraterrestrials. A third idea was that there was a simple warp in the make-up of his brain. The fourth, he said mysteriously, he didn’t want to talk about, except insofar as it was related to idea number two, and that, ‘They are somewhere out there. They have their reasons.’

Geller returned to the experiments. He promised to crack but not break a ring belonging to Yacov’s wife, Sara, and did so, creating a fracture. Puharich sent the ring to a metallurgist at the Materials Science Department of Stanford University in California and several months later, he said, was informed that electron microscopy had shown the fracture in the ring to be of an unknown kind.

For a few more days, Puharich repeated the same tests again and again, determined, at least from his account, not to be fooled. He needed to go back to the States with sufficient evidence of Geller’s abilities to guarantee that he, with Edgar Mitchell’s help, could drum up more financial support for him to do further Geller research in Israel, with a view of opening up the possibility for Uri to be tested scientifically in America.

Puharich was back in Israel in November 1971 to try to find some answers to the fascinating scientific phenomenon he seemed to have uncovered in August. That mysterious reference Geller had made to Puharich back in August

– ‘They are somewhere out there. They have their reasons.’

– had brought to Puharich’s mind something extraordinary that he had encountered back in 1952 when he was just an army medic with an interest in the relatively new field of parapsychology.

At a party in New York that year, Puharich met Dr DG Vinod, a professor of philosophy and psychology at the University of Poona, in India. Dr Vinod was on a lecture tour organized by the Rotary Club. Vinod, like Puharich, was interested in ESP. Two months after meeting Dr Vinod, Puharich accidentally bumped into him again on a train. As they were travelling, the Hindu scholar did a past and future life reading for Puharich by holding his right ring finger at the middle joint with his right thumb and index finger. Puharich found Vinod’s past reading uncannily accurate. On New Year’s Eve 1952, Puharich invited him to his home in Maine, where, at 9pm, the Indian went almost immediately into a deep, hypnotic-like trance.

While he was in trance, Vinod apparently took on a deep, sonorous voice in perfect, unaccented English, which was quite different from his normal, high-pitched, soft, and Indian-accented speech. He said, according to Puharich’s notes:

‘We are Nine principles and forces, personalities if you will, working in complete mutual implication. We are forces, and the nature of our work is to accentuate the positive, the evolutional, and the teleological aspects of existence.’

Vinod went on in this vein for 90 minutes, interspersing his monologue with references to Einstein, Jesus, Puharich himself, and a mathematical equation, which, amusingly, when examined by mathematicians was later found to be ever so slightly wrong. After listening to Dr Vinod while he was in trance over a period of a month, Puharich and a group of helpers were sure they were dealing with something more than messages from the spirit world. They were persuaded that they were being spoken to through Dr Vinod by an extraterrestrial intelligence, which Puharich named ‘The Nine’, supreme alien beings from far beyond our part of the Universe, who had turned their attentions to saving Earthlings from the disastrous consequences of their wars, pollution and so on. Puharich was convinced that the beings, rather than come in person, were using unmanned spacecraft to change conditions on our planet and to contact and train selected humans – starting, naturally, with himself.

At the end of January 1953, Vinod went home, and Puharich heard nothing more from him. Remarkable though the experience of being contacted by extraterrestrials must have been, Puharich seems to have managed to shelve it for 19 years – until, in November 1971, The Nine spoke to him again in Tel Aviv, through the medium of a hypnotized Uri Geller.

For his second trip, Puharich had rented a sixth-floor apartment in the up-market area of Herzliya, north of Tel Aviv, just over a kilometre or so back from the Mediterranean – Puharich was always rigorous about not stinting himself materially. He set up camp from crates loaded with the latest in magnetometers, cameras, tape recorders and countless electronic gadgets Geller could not identify, and started work again. It was agreed between the two men that Geller would give Puharich three to four hours a day, but that this might have to happen at odd times, since Uri was continuing his career of shows and public demonstrations, albeit at nothing like the frequency of the year before.

Again, the experiments started with what now passed for ‘routine’ stuff, Uri accurately picking up three-digit numbers from Puharich’s mind from another room, and Uri moving a compass needle through 90 degrees; this latter, Puharich was intrigued to note, worked better when Uri put rubber bands tightly round his left hand as a tourniquet to block the return of blood from his hand. Maybe that was why the compass moving seemed to exhaust Geller. He complained to Puharich that he found it much less strenuous if he had a crowd of people around him, on whose energy he felt he could draw.

One result that fascinated Puharich was Uri’s ability to bend a thin stream of water from a tap with his hand held a few centimetres away. This, he commented in his notes, was easily done by anyone with an electrically charged piece of plastic, such as a comb, but with a finger, such an effect was unheard of. The electrical charge on Uri’s skin seemed to disappear when it was wet. Another simple test Puharich devised was to see whether Uri could direct a beam of energy narrowly, or whether he produced a random, scattergun effect. He laid out five matchsticks in a long row, on a glass plate monitored by a film camera. Uri was able to move whichever matchstick he chose up to 32 millimetres.

At one stage, Isaac Bentov came to join in the tests with two old friends who had been students at the Technion together in the 1940s. With four researchers poring over Uri together, Puharich noticed that Uri was starting to get bored, and the two had a ‘where do we go now?’ discussion with Bentov and his friends as an audience. Uri was quite clear about the nature of his problem with scientific work. Despite the advice of Amnon Rubinstein, he simply still could not see the point of it. He elaborated eloquently about how nothing mattered to him so much as he was making money, and the freedom that went with that. His life, as he saw it, had been a constant struggle to assert his freedom, with money being the ultimate way to achieve it. When the chance came to show off his powers, with his increasing love of performance, and to make money at the same time, he grabbed it. ‘I want to be known. I want to be successful. If you want to work with me, you will have to deal with my need for fame and fortune. That’s it,’ he concluded to Puharich.

Puharich and Bentov were saddened by what they saw as the small-mindedness of this ‘unabashed egomaniac’, as Puharich described Geller. They all went out for dinner. On the way home, late at night, Uri insisted on giving a display of blindfold driving. This did not impress Puharich much – he knew it was an old magician’s trick and how it was done, even so, was surprised by how accurately Uri managed to drive, at up to 80kph for three kilometres. He was even more surprised when Uri said he could see a red Peugeot coming, and a few moments later a red Peugeot appeared from round a bend ahead. Back at the apartment, Bentov started a late-night conversation about the soul, and how he believed Uri’s was so much more evolved than other people’s, but that it had become coarsened by poverty and struggle. He did not have to be so selfish and financially obsessed, Bentov said.

Uri seemed mildly interested and asked how he could find out about his soul; Puharich leapt at this and offered to hypnotize Geller. Uri was reluctant at first, but Puharich was already compiling ever more detailed notes with a view to writing a book on his Uri Geller experiences and was keen on the idea. He convinced Uri that hypnotism would be the best way to go back to his childhood and recall vital material he had forgotten, maybe explore the incident in the Arabic garden. Uri said he knew about hypnotism, being in show business, and that although he believed himself to be unhypnotizable, he would happily give it a try.

As the guests left Puharich’s apartment, one of Bentov’s friends took Puharich to one side and said, ‘You know, we have a word in Hebrew for a kid like Uri –

puscht

, a punk. He really is insufferable. I don’t know how you can be so patient with him.’ Puharich says that he replied, ‘I feel he is so extraordinary that he is worth almost any effort.’

On 30 November, Uri was performing at a discotheque in Herzliya. Puharich and Bentov were planning the first hypnosis session with Geller that night, and went to see him at the louder-than-loud event. Puharich later reported being so depressed by the tawdriness of the show, just as he had been by the cabaret Uri was in at Zorba back in August, that he almost wondered if he wanted to continue with the Geller experiment any longer. Uri nevertheless turned up at Puharich’s apartment with his young girlfriend, Iris, a model, and lay down on the living-room sofa just after midnight. Puharich asked him to count backwards from 25, and was pleased to note that by the time he got to 18, Geller was in a deep trance. He would remain in it for an hour and a half.

Both Puharich’s and Uri’s accounts of what happened over the forthcoming weeks almost need to come with a mental health warning; what follows certainly requires a great deal of forbearance on behalf of the reader. While reading this material, and more likely than not scoffing at it, it is important, however, constantly to bear in mind one or two things.

Firstly, that Uri, while still being rather embarrassed by his and his then-mentor’s accounts of events, does not attempt to deny or suppress them, but rather to attempt to explain, which is far from an easy job. The obvious conclusion is that he was extravagantly conned by Puharich. Yet if Geller stands accused of one thing by his detractors, it is of being a cunning deceiver – not of being gullible or impressionable himself. Secondly, Puharich was many things, but not a rogue or a charlatan, at least according to those who knew him, and in many cases clashed with him. One can only ask the reader to keep this in mind for the next few moments.

Once Uri was fully under the hypnotic trance on the sofa in the Herzliya apartment, Puharich asked him where he was. Geller talked initially about being in the caves back in Cyprus, with Joker, his dog. ‘I come here for learning,’ Uri said. ‘I just sit here in the dark with Joker. I learn and learn, but I don’t know who is doing the teaching.’ Puharich asked what he was learning. Geller replied that it was a secret, about people who come from space, and that he would tell Puharich all about them, but not yet. Uri then lapsed into Hebrew, with Bentov doing a running translation. After telling of many trivial childhood incidents, he finally talked about the light in the Arabic garden opposite his parents’ flat in Tel Aviv.

He named the day it happened as 25 December 1949, a date that obviously has some resonance, although not, it must be noted, in Israel, of course, where Christmas Day is just another working day. Uri described the light he saw in the garden as a large, shining bowl, from which a figure appeared, faceless but exuding what Uri said was ‘a general radiance’. Then the figure raised its arms and held them above its head, so it appeared to be holding the sun. It then became so bright that Uri passed out.