The Second Spy: The Books of Elsewhere: Volume 3 (2 page)

Read The Second Spy: The Books of Elsewhere: Volume 3 Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

“Olive!” Mrs. Dunwoody called from the foot of the stairs. “You’re now seventeen point five minutes late and counting!”

With a sigh, Olive tucked Hershel back under the covers. She stood up in bed, wavering for a moment on the squishy mattress, and then jumped as far away from the bed as she could get without crashing into another piece of furniture. Olive did this every morning, just in case something with long, grabbing, painted arms was waiting underneath the bed. From several feet away, she bent down to check under the dust ruffle. No Annabelle. Olive opened her closet with a practiced yank-and-leap-backward maneuver. This way, if Annabelle were indeed waiting inside, Olive would be hidden behind the door. She peeped through the door frame. No Annabelle. Olive tugged on a clean shirt, carefully arranging the

spectacles inside the collar, and hustled out into the hallway.

Even on clear September mornings, the upstairs hall of the old stone house remained shadowy and dim. Faint rays of sun glinted on the paintings that lined the walls. Olive’s fingers gave a twitch. The temptation to put on the spectacles and dive into Elsewhere tugged at her like a strand of hair caught in a rusty zipper.

“Olive!” called Mrs. Dunwoody. “There are just thirty-four minutes until the school day begins!”

With a last longing glance over her shoulder, Olive headed for the stairs, slipped on the top step, and just managed to catch herself on the banister before toppling rump-over-teakettle down the staircase.

Because it was Olive’s very first day of junior high school, Mr. Dunwoody had fixed a special pancake breakfast. Mrs. Dunwoody kissed Olive on the head and told her how grown-up she looked. Then Mr. Dunwoody made her pose for a photograph on the front porch holding her book bag and her fancy graphing calculator, and after that, Mrs. Dunwoody drove her to school because she had already missed the bus and if she walked she

would

have been tardy by more than fifteen minutes. And yet neither of her parents noticed that Olive (whose brain was even

more distracted than usual) was still wearing her pink penguin pajama bottoms with ruffles across the seat of the pants.

But the kids at school did.

Everyone in Olive’s homeroom laughed so loudly that students walking down the hall stopped to see what was so funny. One boy laughed until his face turned the color of kidney beans, and he had to go to the nurse’s office to use his asthma inhaler.

A girl with long, dark hair and a sharp nose—a girl who, Olive noticed, was wearing

eyeliner

—leaned across the aisle to Olive’s desk. “They’re mean, aren’t they?” she asked. “Don’t worry about them,” the girl went on as Olive tried to squeeze out an answer. “I think your pants are

adorable

.” Here the girl raised her voice a little bit, so that everyone around them could hear. “But didn’t you know that the

kindergarten

is in another building?”

All the kids went off on another roar of laughter, and Olive wished she could sink down into the cracks in the floor with the eraser scrapings and pencil dust.

The morning didn’t get any better. During her second class, when the students were supposed to stand up and tell about themselves, Olive mumbled that she was eleven, that her parents were both math professors, that her family had moved to town at the beginning of summer, and—because she couldn’t

think of anything else to say—that she had a birthmark shaped very much like a pig right above her belly button, which was true, but which she certainly hadn’t planned to admit to anyone.

During her third class, Olive asked to go to the restroom and got so lost afterward that she wandered around the building for almost an hour and wound up in a storage room behind the gymnasium, where a friendly janitor finally found her.

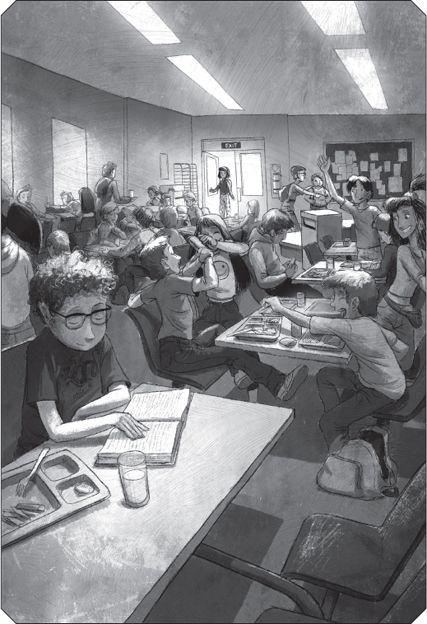

When lunchtime came, Olive tiptoed into the cafeteria with a fleet of butterflies doing death-spirals in her stomach. The tables were already crowded with students (Olive had gotten lost on the way to the cafeteria too), and everyone was shouting and laughing and stealing food from one another’s trays. She blinked around, wondering how she was ever going to feel brave enough to sit down at one of those tables, and whether it would be dangerously unsanitary for her to take her lunch back to the restroom and eat it there, when, like one stalled car in a sea of roaring traffic, a quiet table surfaced amid the chaos.

The table was empty except for one rumpled boy. A boy with smudgy glasses, and messy brown hair, and a large blue dragon on his shirt.

Large blue dragons had never looked friendlier. Olive made a beeline for the table.

“Hi, Rutherford,” she said, smiling for the first time all day.

Rutherford Dewey glanced up. Before Olive had even had time to plop into a chair, he asked, “Have you heard about the pliosaur skull that was discovered on the Jurassic coast?”

There were several questions Olive could have asked in response to this. (“Where’s the Jurassic coast?” “What’s a plierssaur?” “Is that its name because it looks like a pair of pliers?”) But the only answer she could give was “No.” So she gave it.

“It’s a fascinating find,” Olive’s neighbor went on, in a rapid, slightly nasal voice that was only partially muffled by a mouthful of chicken salad. “The skull itself is nearly eight feet long. The pliosaur’s entire body probably measured around fifty feet, which is more than twice the size of an orca.”

“An orca is a killer whale, right?” asked Olive, unwrapping her sandwich.

“Yes, although the name ‘killer whale’ is a bit unfair. The orca isn’t an especially murderous creature. Besides, all of us are killers of

something

.”

“No we’re—” Olive cut herself off mid-argument, wondering if dissolving something evil that came out of a painting counted as “killing.”

Rutherford watched her take the first bite. “What’s that in your sandwich?” he asked.

“Peanut butter.”

“Then you’re a peanut killer. It’s inevitable. Each of us has to kill to survive.”

Olive squirmed. For the hundredth time that day, she touched the lump of the spectacles underneath her shirt, making sure they were still there.

“Don’t worry,” said Rutherford. “My grandmother will be keeping a very close watch on the neighborhood while we’re at school. She’ll be watching your house especially.”

Olive glanced up into Rutherford’s intent brown eyes. Not for the first time, she had the strange feeling that Rutherford must have been reading her mind. Of course, she reminded herself, it wouldn’t be hard for him to

guess

what she was worrying about.

“Your grandmother hasn’t seen any sign of…of

Annabelle,

has she?” Olive asked, dropping her voice to a whisper.

Rutherford shook his head, looking unconcerned. He looked just as unconcerned a second later, when a wad of plastic wrap sailed through the air and beaned him on the head. “No. No sign of her presence,” he went on as a group of boys at a table nearby slapped each other’s hands and sniggered. “And my grandmother has also placed a protective charm on your house, which prevents anyone who isn’t invited inside from entering the house itself. She uses the same kind of

charm on ours. It dates back to the middle ages, when it was placed on the walls of castles and fortresses, and thus it doesn’t protect outdoor spaces; however, it is still quite effective.” Noticing that Olive’s eyes were beginning to glaze, Rutherford changed the subject. “Have you heard about Mrs. Nivens?”

Olive almost inhaled a chunk of sandwich. She looked around, making sure no one else had heard. “What about her?”

“The police have declared her a missing person. They’ve searched her house and everything. Now it’s locked up and they’re keeping it under surveillance.”

Olive put down her sandwich. “I don’t think they’ll figure out what really happened. Do you?”

One of Rutherford’s eyebrows went up. “You mean, that Mrs. Nivens was actually a magical painting trying to serve a family of dead witches, one of whom finally turned on her?” The eyebrow came down again. “I think it’s highly unlikely.”

“Yeah.” Olive paused. “They sure won’t figure it out from looking around her house. Everything is so

normal.

” Olive’s mind darted back to the evening when she, Morton, and the cats had tiptoed through the eerily clean and quiet rooms of Mrs. Nivens’s house—a house that had hidden Mrs. Nivens’s secret for nearly a century.

A not-quite-empty carton of milk hit the center

of their table, exploding in a fountain of tepid white droplets. The boys at the nearby table guffawed.

“It’s been my experience that those people who seem the most ‘normal’ are in fact the most dangerous,” said Rutherford, wiping a drip of milk off the end of his nose.

Olive dragged her penguin-dotted legs through the rest of the afternoon. She spent science class staring at the shelves of beakers and test tubes, remembering the chamber full of strange, murky jars that she’d found beneath the basement of the old stone house, and missing half of the instructions for the very first assignment. Next, she spent history class thinking about all the people Aldous McMartin had trapped inside his paintings, becoming so absorbed that she didn’t hear the teacher calling on her until he’d said her name three times. But the minutes ticked by, and the last hour of the day crawled closer, and finally, Olive found herself climbing the stairs to the third floor and trudging along the hall to the art classroom.

Olive pulled up a metal stool to a high white table as far away from all the other students as she could get. Then she waited.

And waited.

And waited.

“Where do you think the teacher is?” asked one of

the noisy girls at the front of the room, after several minutes had gone by.

“Maybe we should call the office and tell them she’s not here,” said the noisiest girl of all, craning around on her stool so that Olive caught a glimpse of eyeliner.

But before Olive could give another thought to makeup or meanness or penguin pajamas, there was a sound outside the art room door. It was a jingling, stomping, crinkling sound, as though a reindeer pulling a sleigh made of candy wrappers was trying very hard to get in. A key rattled in the lock. “Darn it,” said a muffled voice. The doorknob rattled again. In another moment, the door burst open, revealing a woman standing in the hallway.

Her arms were filled with paper and plastic bags, which in turn were filled with other things—pipe cleaners, canisters of salt, and something that appeared to have once been a massive starfish—and her neck was looped with lanyards and whistles and cords and pens and beads and bunches of keys, all clattering together like an office-supply wind chime. Long, kinky tendrils of dark red hair could be seen above the bags, standing out in every direction. With a grunt, the woman dumped the armload of bags on the front table and blinked around at her wide-eyed students.

“Of course, the door wasn’t locked at all,” she said, as though they were already in the middle of a conversation.

“You all got in here. And

you

don’t have keys.” She glanced into one of the overstuffed paper bags. “Oh, shoot. I think I cracked my cow’s skull.” Sighing, the woman turned toward the chalkboard. “My name is Ms. Teedlebaum.” She wrote something that looked like “Ms. Tood—” and ended with a squiggle. The noisy girls at the front of the room snorted with giggles.

Ms. Teedlebaum turned back toward the class. “We’re going to begin this unit at the beginning,” she said, putting her hands on her hips. The lanyards and cords and keys swayed and jangled. “And we’ll start with a subject you’re all familiar with. Yourselves.” She turned one of the paper bags upside down, and a flood of pencils and watercolor palettes and oil pastels and chalk bounced out onto the table. Some of the flood bounced all the way to the floor. “You can use whatever medium you like. There are mirrors in that cabinet, and paper is on that shelf. Get started.”

With a swish of her long skirts, Ms. Teedlebaum picked up one of the paper bags and sailed toward her desk. At least, Olive

thought

it was a desk. It looked more like a sandcastle built out of art supplies, but there was probably a desk in it somewhere.

“But what are we supposed to do?” asked the girl with the eyeliner, in a tone that strutted along the line between

not quite polite

and

very rude.

Ms. Teedlebaum glanced up from behind the sandcastle. “Self-portraits. Didn’t I say that? No? Yes. Self-portraits. Draw, paint, or color yourselves. Whatever feels right to you.”

With more muttering and giggling, the class jostled each other for the best supplies. Olive waited until everyone else was seated again before slinking across the room. The only things left on the front table were two charcoal pencils and a set of mostly broken chalk. She took the pencils back to her seat. Then she stared down at her own reflection in the little round mirror.

Staring back up at her was a girl with stringy brownish hair—a girl with a suspicious lump beneath her shirt that might have been the outline of some very old spectacles. The girl’s eyes met Olive’s. Her eyes were wide and watchful, and more than a little bit afraid.