The Second Spy: The Books of Elsewhere: Volume 3 (10 page)

Read The Second Spy: The Books of Elsewhere: Volume 3 Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

All she needed was a few more hours to finish the portrait.

Olive slid the spectacles out of her pajama collar and placed them on her nose. The figures in the painting shifted slightly, turning their featureless faces one way and then the other. Olive quickly tugged the spectacles off again—first, because the blank, moving faces were a bit creepy, and second, because she wanted to postpone the excitement of seeing Morton’s parents come back to life for good, at last. Of course, they wouldn’t be his

real

parents, Olive admitted to herself. She still hadn’t found the

real

versions, if they were anywhere to be found. But these parents would be something just as good—or maybe even better. If Olive had mixed the paints correctly, they would be just like Annabelle’s living portrait, complete with thoughts, personalities, and memories, but undying and unchanging. Just like Morton himself.

Olive leaned back against the pillows, listening to

the voices at the other end of the hall. Her parents were still in their own bedroom, getting ready for another day crammed with equations and solutions.

She moaned again, loudly this time.

“Mmmmoooooaaaah,” she groaned, holding her stomach. “Aaaaaaooooow.”

The voices at the end of the hall stopped speaking. A moment later, Olive heard her mother’s footsteps tapping along the hall.

There was a soft knock. “Olive?” said Mrs. Dunwoody. The door creaked open, and her mother’s face appeared in the gap. “Are you all right?”

“I don’t feel so good,” Olive mumbled.

“What’s wrong?”

“My stomach. And my head. I feel all achy,” Olive moaned, squinching her eyes shut. “Maybe it was that pizza.”

“Well, you did eat it awfully quickly.” Mrs. Dunwoody sat down on the edge of the bed. She pressed her cool palm to Olive’s forehead, which felt nice even though Olive didn’t have a fever.

“I don’t think…” said Olive, pretending to run out of breath, “…I don’t think…that I can make it…to school today.” She peeped through her eyelashes at Mrs. Dunwoody.

Her mother nodded. “I’ll call the math department and let them know that I won’t be coming in. With

this late notice, they’ll have to cancel my classes, but—”

Olive’s eyes popped open. “No!” she said, much too healthily. “I mean…

no

…” she groaned, making her eyelids droop again. “You don’t have to do that. You should go to work. I’ll be fine here by myself. I just want to stay in bed and sleep.”

Mrs. Dunwoody frowned. “I don’t want to leave you at home alone if you’re feeling sick.”

“I think it’s just the pizza. Really. If I start feeling worse, I’ll call your office right away, I promise.”

Mrs. Dunwoody’s frown remained firmly in place. “Wouldn’t you like me to call Mrs. Dewey and ask her to come over to stay with you?”

“NO!” Olive nearly shouted. Then she flopped back on the pillows, hoping that she looked exhausted by the effort of nearly shouting. “I’ll be fine here,” she panted. “I just want to be by myself.” Beneath her lowered lashes, she glanced at the painting. Morton’s father’s head looked a little lopsided. She would have to fix that.

Mrs. Dunwoody rose slowly to her feet. “Well…” she said reluctantly, “I’m done with my classes at noon on Fridays. I’ll come straight home afterward, which means I should be here by twelve eighteen.”

Olive gave her mother a weak little smile. “Okay.”

“But if you start feeling worse, you call me

and

Mrs. Dewey immediately. Agreed?”

“Agreed,” said Olive, closing her eyes.

“Get some rest,” Mrs. Dunwoody whispered. “We’ll lock the doors. Don’t let anyone in.”

A ripple of fear washed through Olive’s stomach, and for a split second, she actually

did

feel nauseous. “I won’t,” she whispered back.

The bedroom door gave a click. Olive held still, clutching the covers, while downstairs, the coffee maker hissed and two briefcases thumped and finally the heavy front door banged shut. She waited until she heard the car rumble softly away down Linden Street.

With a bounce, Olive sat up and kicked off the covers. She raced across the room to the canvas, too intent on the adventure ahead of her to remember to jump off of the mattress or to check under the bed. Her own smiling face glowed back at her from the vanity mirror. She checked the contents of the cookie sheet, still covered by the damp washcloth. The paints in their bowls looked thicker than they had yesterday, but they weren’t yet dry. Olive glanced at the clock beside her bed. She had just over five—no, four—hours until her mother would come home. She had to work fast.

Olive darted back and forth between the vanity and the bedside table, arranging brushes, paints, and canvas. Then she hopped back on top of the bedspread

and lifted the canvas into her lap. Olive mixed a batch of peachy-brown paint and settled down to work.

She had straightened the man’s slightly crooked head and was just beginning to outline his nose when the hairs on her neck gave a little prickle. Olive felt a zing of worry shoot through her body.

She was being watched.

Slowly, she turned her head toward the bedroom door—the door she

knew

had been closed just moments before—and found herself staring into a single bright green eye. Where another bright green eye should have been, there was only a small leather eye patch. Captain Blackpaw had come to visit.

As sneakily as she could manage, Olive tossed the damp cloth back over the contents of the cookie sheet. “Harvey!” she gasped. “You startled me.”

“Aye,” the cat snarled proudly. “Any landlubber would be startled at the sight of the fearsome Captain Blackpaw.”

“Mmm,” said Olive.

“And what be ye doing abed so late on this fine Friday morning?” asked the cat, tilting his head.

Olive sidestepped the question. “You know that it’s Friday?” she asked. Often, Harvey didn’t seem to be aware of what

century

it was, let alone what day of the week.

“’Course I know that,” said Harvey. “’Tis Friday, the ninth of September, 1725.”

Yes. There it was.

Olive thought about telling Harvey that there was no school today, or that she had been grounded and forbidden to leave her own room, or that a band of marauding polar bears who only ate sixth graders had been spotted in the neighborhood. But in the end, she decided to stick with the lie that had worked once already. “I’m not feeling too good today,” she said. “I think I’m sick.” Then she added a small cough for good measure.

Harvey’s uncovered eye widened. “Scurvy?” he asked hopefully.

Olive shook her head.

“The itch? The pox?”

“I think it’s just bad pizza.”

Harvey looked confused.

“Well…I’d better get back to resting,” said Olive, plumping her pillows in a hinting sort of way.

“Indeed,” said Harvey. “If ye need me, raise the flag and fire the cannons.” He bounded back through the door with a piratical flourish, shouting, “Captain Blackpaw sets sail for the cove!” A moment later, the sound of running paws had receded down the hallway.

Olive got up and closed the bedroom door again. Then she returned to work on the painting.

She worked until the bowls of paint were nearly empty and her fingers were cramped from holding the brush. Her neck had a funny crick in it, and her face hurt, probably because she’d been smiling back at the people in the painting the entire time. But the portrait was finished. Gazing up at her from the canvas were two painted people in old-fashioned clothes, proudly displaying all the limbs, feet, and fingers that any two real people ought to have. Olive looked from the photograph to the painting yet again. Yes, she had done an awfully good job, if she did say so herself.

She spent fifteen minutes pointing a hairdryer at the canvas, until the paint had gone from shiny and wet to less-shiny and dry. Olive reached out with the tip of her littlest finger and touched the canvas. No paint came off on her skin. The portrait was done.

With a flood of excited bubbles fizzing through her fingertips, Olive settled the spectacles on her nose. Then she tilted the canvas up against her pillows, climbed onto her knees, and got ready to meet Morton’s parents for the very first time.

11

T

HE SURFACE of the canvas smooshed and dimpled around Olive’s face. To someone who had never pushed her face into a painting, this might have felt abnormal. To Olive, it not only felt normal, it felt

delightful

. It meant that her painting was working. She had done it right. As though she were diving through a doorway made of warm Jell-O, Olive squished her body into the canvas.

One moment, she was crawling across her own rumpled bedspread. The next moment, her hands and knees were scraping against the rough surface of a canvas floor. Being short on time, Olive hadn’t painted much of a background for Morton’s parents. The room they waited in—if you could call it a room—was just an off-white square of slightly crooked lines.

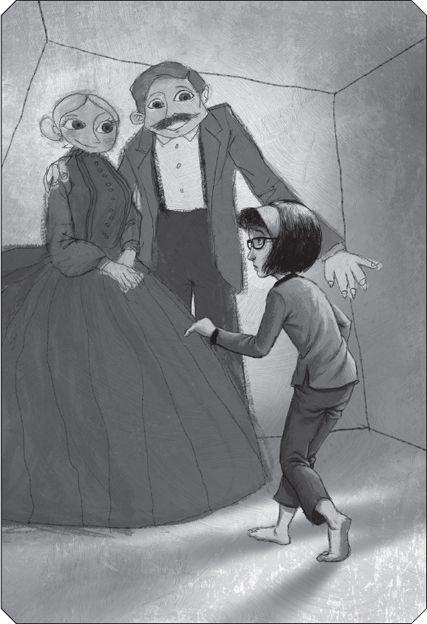

But the background didn’t matter. All that mattered was that Morton’s parents were there, smiling and posing, just as Olive had painted them. Their eyes followed her as she got up off her knees and stepped closer.

“Hello,” she said shyly. “You’re—um—you’re Mr. and Mrs. Nivens, aren’t you? You’re Morton and Lucinda’s parents?”

The smiles on the painted faces didn’t waver.

“I’m Olive. Morton is my friend.”

Olive waited for Morton’s parents to answer. Morton’s father took his hand off of his wife’s shoulder, where Olive had painted it. Now that both arms were dangling at his sides, Olive realized that one was stumpier than the other. And it wasn’t just a little bit stumpier. It was a lot stumpier. Olive always did have trouble with foreshortening.

Morton’s mother merely stared at Olive, her smile affixed to her face like something pinned to a bulletin board.

Neither of them spoke.

“Umm…” said Olive. “Morton has always just called you ‘Mama’ and ‘Papa.’ Is there something else I should call you? Your first names, maybe? Or is ‘Mr. and Mrs. Nivens’ all right?”

The painted people didn’t answer. But they nodded enthusiastically. Morton’s father went on nodding quite a lot longer than was necessary.

Olive took a step closer, studying their smiling faces. She’d made Morton’s mother’s eyes a touch too big. Olive had a habit of doing that in her artwork. All of her people turned out looking as though there might be at least one lemur hanging on the family tree. And, if she was honest with herself, Morton’s father’s neck was just a smidgeon too short. If she was really,

really

honest, she might admit that his collar appeared to be trying to swallow his head. But his

face

was fine, Olive assured herself. The features looked just like they had in the photograph. Morton would recognize him. He would recognize them both. He would be so happy to see them.

“If you’ll come with me, I’ll take you to Morton. He still lives in your old house. Sort of.” Olive struggled on while the portraits watched her, smiling and staring. “So, if you could just hold each other’s hands and follow me…”

Morton’s mother tottered unsteadily forward. Olive suspected that she had made Mrs. Nivens’s lower half a bit too long, as she often did in drawings where there was a trailing, puffy skirt involved. And perhaps the ruffled silk of the skirt had come out rather stiff…but it was hard to paint realistic-looking cloth. Olive eyed her work, trying to convince herself that Mrs. Nivens

didn’t

look like a big black funnel with a head and torso dribbling backward out of the top.

She glanced at Morton’s father. Fortunately, he was already standing, and his legs didn’t seem to be too long for the rest of his body. However, Olive had forgotten to paint the outline of knees inside the solid black tubes of his pants. When he stepped toward Olive, he had to swing from one straight leg to the other, like a pair of walking chopsticks.

“Okay,” said Olive, in a voice that had gotten a bit wobbly. “Now hold on to my hand, and hang on to each other, and do what I do. We have to move fast.”

Olive reached out toward Morton’s father. He took her hand in his big painted one. There wasn’t time to study it for long, but Olive noticed that his hand looked a bit stiff and sausagey, with all its fingers poking out in different directions, like the limbs of a starfish.

Holding on to the portrait’s hand, Olive crawled back out of the canvas and onto her squishy mattress. Morton’s parents followed her without too much trouble, although his mother did have to squirm a bit to get her massive skirts through. Olive tugged them both across her bedroom and into the upstairs hall.

There, standing in the dusty beams of daylight just outside the painting of Linden Street, Olive got her first clear look at her handiwork. And, as she looked, the realization flooded over her that what looks fine in a painting might be

terrifying

in real life.

The portraits’ faces were uneven and askew. They

were flat where they should have been rounded. They were bumpy where they should have been smooth. Their limbs were rigid and awkwardly angled. Morton’s mother’s eyes, which had looked just a little bit too large from farther away, looked gigantic up close. Their color was flat, dark, and empty, without a reflective spark of light to bring them to life. And Morton’s father’s mustache, which Olive had formed with such careful brushstrokes, didn’t look like hair at all. Instead, it looked like some small, furry animal that had collapsed beneath his nose, but which might regain consciousness at any moment. Olive wasn’t sure if it was how she had mixed the paints, or if it was simply her lack of artistic skill, but even the hues of their skin and hair seemed impossibly bright, inhuman, and

wrong.