The Search for the Red Dragon (13 page)

Read The Search for the Red Dragon Online

Authors: James A. Owen

“Very funny,” said Aven.

“Pun intended,” said Bert. “If I can’t joke about imminent death, then I might as well just resign.”

“Resign from what?” asked Jack.

“Depends on the day,” said Bert. “Aven, I wanted to ask—when the Cartographer translated the name of the islands as ‘Lost Boys,’ you reacted very noticeably. Why is that? What does that phrase mean to you?”

The fact that Aven didn’t immediately reply was an indication of just how deeply she felt about the question. Finally she handed her tools to one of the fauns and stood against the cabin wall, her arms folded.

“Obviously it’s also a reference to Jamie and Peter’s Lost Boys,” she explained. “It was the name that all the children who came to Peter’s secret hideaway went by—but he wasn’t the one who started using it. It began long before Peter’s time. And I also didn’t know it referred to a place—especially one that guards the Underneath.”

“But why would that bother you?” asked Jack. “We’ve mentioned the Lost Boys several times, and you never blinked.”

“It wasn’t just mentioning them,” Aven said. “I just suddenly realized that I might have actually

been

to the Underneath before. I think it’s what Peter and Jamie called ‘the Nether Land,’ and I know another way to get there.”

Jack started. “You mean a way other than the portal? That’s wonderful!”

Aven shook her head. “There

is

a way, back in your world. But it won’t do us any good.

“It…was meant to be a secret,” she continued, with a hesitant glance at her father. “It’s how Jamie was able to go back and forth to the Archipelago without using the Dragonships.”

“Ah,” said Bert. “I’ve often wondered about that. It was one

of Jamie’s great secrets,” he told Jack. “He refused to work on any maps or annotations of the Nether Land, and he stoutly refused to discuss it when the subject came up. It was one of the first conflicts we had with him as a Caretaker.”

“There is a wardrobe in London,” Aven went on, “one of two that originally belonged to Harry Houdini. He claimed to have built them himself, but Jules always suspected that he stole the principles behind them from the inventor Nikola Tesla.”

“You mean ‘borrowed,’” said Bert mildly.

Aven shook her head. “Stole. Tesla tried to have him arrested for stealing his papers, but Houdini ate the papers in question, then broke himself out of jail to ask the magistrate to release him for lack of evidence.”

“I see. Forget I asked. You were saying?” said Bert.

“Houdini built two wardrobes for use in his stage act,” said Aven. “He or a member of the audience could enter one, then instantly appear in the other, which was placed at the opposite edge of the stage. He pushed the limits further with every performance, moving one wardrobe to the balcony, then the lobby, and once even to the street outside, where a surprised volunteer emerged and was nearly run over by a carriage. Shortly after that, the trick was discontinued, and he never performed it in public again.”

“The trick had lost its appeal?” Jack asked.

“Hardly,” said Aven. “It was the biggest draw of the day. But he found a more useful application for it. Because of his skill as an escape artist, he was approached by both Scotland Yard and the United States Secret Service to work for them as an intelligence-gathering agent. His touring show was his cover, and in the rare

event he did get caught by a foreign agency, he could simply free himself and walk away.”

“Handy,” said Jack. “Where do the wardrobes come in?”

“Houdini realized that the ability to instantly transport himself from any location would make him unsurpassable as a spy,” said Aven. “So he would often arrange to have one of the wardrobes delivered to government offices, or royal residences, on the pretext that the delivery was a mistake. It was always returned to him, but in the meantime he could count on having an open door to wherever it was.”

“And the other wardrobe could be kept in his dressing room for a convenient escape,” said Jack. “Impressive.”

“Exactly,” said Aven. “There were the occasional sightings of him in places he wasn’t supposed to be—but how can you bring charges against a man who was seen onstage only minutes later, by an audience of five hundred, in a theater a thousand miles away?”

“That explains something else,” mused Bert. “Houdini and Conan Doyle used the wardrobes to avoid Samaranth, didn’t they?”

“Yes,” Aven said, suppressing a giggle. “They did. They were crisscrossing Europe trying to stay out of sight while you tried to talk sense into Samaranth. Giving up the wardrobes was part of the offer they made in exchange for his not roasting them whole.”

“And he gave the wardrobes to the next Caretaker, who was Jamie,” continued Jack.

“Right,” said Aven. “That was around the time he first met Peter, who had learned a way to cross the Frontier on his own, using the wings Daedalus the Younger made for all the Lost Boys. Somehow they were able to place one of the wardrobes in the

Nether Land, and they kept the other at Jamie’s house, so that either or both of them could cross at will. I’ve used it more than once myself to get to the Nether Land.”

“After a visit with Jamie in London, I’d assume?” asked Bert.

Aven blushed, and tried to frown, but couldn’t quite manage it. “Yes. That too.”

“That’s why it was a surprise to you that the Nether Land might be in the Underneath,” said Jack. “You’ve never traveled there any other way, have you?”

Aven shook her head. “It was one of Peter’s rules. He wouldn’t permit outsiders to know the way there—and I was an outsider. I haven’t been back there in years, but I think Jamie’s wardrobe is still in London.”

“It is! I saw it myself. This is grand news.” Jack exclaimed, clapping his hands. “If we can get back to London, we can simply enter the wardrobe at Barrie’s town house and be sent right to the Underneath without the return trip.”

Again Aven shook her head. “It won’t work. When Jamie left, I wasn’t the only one who felt betrayed. Peter kept the wardrobe but locked it so it couldn’t be used.”

“But he’s the one who sent a messenger to find the Caretaker,” said Bert. “Why didn’t he simply send her through the wardrobe?”

“There’s only one reason,” said Aven darkly. “Because he wasn’t able to.”

At the other end of the ship, John and Charles had been sitting in the light of the cabin’s oil lamps, dissecting their copies of Tummeler’s

Geographica

for any scrap of useful information, but with little result.

John dropped his copy, kicking it across the deck—an action he immediately regretted, and he quickly retrieved it and buffed the cover with his shirtsleeve.

“I shouldn’t be angry with Tummeler,” he said to Charles, who had been watching from a nearby perch atop a broken section of railing. “He certainly can’t be expected to have included every notation in the

Geographica

. It’s quite an accomplishment that he recalled as much as he did. But it’s not going to be a help. Not with this.”

Charles nodded as he bit into an apple from the ship’s stores. “You’re probably right about Tummeler’s

Geographica

. Then again, so was Aven—it’s not so much useful as it is interesting. Did you notice on one of the spreads, he annotated the description so thoroughly that there’s only room for one small corner of the actual map? I also hadn’t realized how frequently he found an opportunity to include some of his recipes in and around the texts. Enterprising fellow, is our friend the badger.”

“I just can’t help thinking this is once again all my fault,” said John. “I’m a professor now. A teacher. I’m well educated. And I’m one of only a few people in the world who is capable of using the

Imaginarium Geographica

—but I can’t even manage to keep track of it when I really need it.”

“Cheer up, old chap,” said Charles. “From what I’ve heard, that Einstein fellow is redefining the scientific laws of the universe, but he can’t make change at the market. Maybe it’s the price you pay for being the best at something.”

“You’re not helping,” John said morosely.

As they talked, the horizon was beginning to brighten from the dark of night’s passage to the cobalt gray of dawn’s arrival. One

by one, the stars began to fade out, with the exception of a single bright point of light low in the western sky.

“That’s heartening at least,” John remarked, indicating the solitary star. “One of my earliest stories was about the morning star and an ancient myth.

“When I was a student, I read an Anglo-Saxon poem about an angel called Earendel. It so impressed me, so inspired me as both an allegory and a literal representation of the light of faith, that I researched it for more than a year. I was certain I’d discovered an Ur-Myth—one of the original stories of the world.

“Earendel, or Orentil, as he was called in the older Icelandic version of the tale, was a mariner who was fated to sail forever in the shadowy waters of an enchanted archipelago,” John continued. “I revised the mention of the star to represent his beloved, who drew him up from the darkness into the heavens. And the poem that resulted was the beginning of all the mythologies I’ve been working on ever since.”

“And the beginning of your apprenticeship as a Caretaker,” said Bert, who with Aven and Jack had approached them while John was narrating. “It was ‘The Voyage of Earendil’ that first brought you to Stellan’s—and my—attention.”

“I didn’t know that,” said John, who was still watching the morning star. “It’s an interesting foreshadowing to what followed, don’t you think?”

“Maybe more than you realize,” said Charles, who had risen from his seat and was gripping the railing alongside John. “Look,” he went on, pointing excitedly. “Your morning star is coming this way.”

He was right. The point of light that appeared to be a star was

only growing brighter as the sun rose, and it wasn’t moving in a straight line, but seemed to be bobbing and weaving.

“A bit erratic for a star,” Jack said.

“Not erratic,” corrected Bert, with tears in his eyes. “She’s just following the signal.”

The star dipped suddenly and came into full view in front of the cresting sun. Each of the companions gasped in turn, as they realized that John’s star had

wings

, and the point of light was a fiercely shining Compass Rose.

It was Laura Glue.

Seeing the

Indigo Dragon

, she let out an excited whoop and flew directly toward them.

In one hand she was clutching the Compass Rose that had led her to them in Oxford.

And in the other she held the

Imaginarium Geographica

.

HAPTER

T

WELVE

Dante’s Riddle

Despite the circumstances,

it was a glorious reunion. There are rare moments in human experience, Jack thought to himself, that fill one to bursting with emotion. Many are based on relationships, or personal experiences, and are too individualized to really be shared or explained. But there is one emotion that is universal, in which an infinite amount of gratitude may be felt with the smallest pinch of experience: the knowledge that one has not been forgotten.

Seized by joy, the companions passed the elated Laura Glue from one to another, hugging her tightly and laughing. All save for Aven—who seemed happy to see the girl, but was strangely removed from the reunion the others were celebrating.

“I knowed I could find you!” she said, beaming. “I told Jamie I just knowed I could!”

“And so you did!” declared John, who had rather delicately taken the

Geographica

from her grasp. “I can’t believe you came, Laura Glue.”

“I wanted to show Jamie my wings,” she said. “So we went out to the autogobile where you’d put them, and that’s when he saw the book, and boy, did he call you lots of names.”

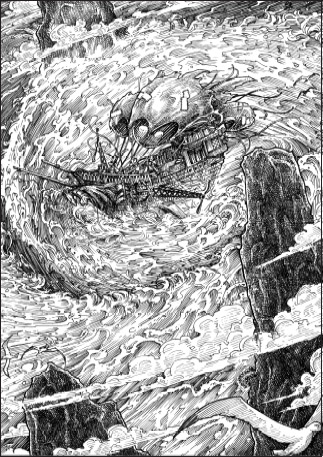

…the rotating water…was forming a gigantic whirlpool.

John reddened. “I’d imagine so. But how did you find us?”

She held up the Compass Rose. “Same way as before. Jamie knew how to remake the mark, and he said you’d be needing your book right away. So we had tea, and when it was night, we went to the park, and…”

Laura Glue paused, thoughtful. “He said that it was ap—apro—”

“Appropriate?” Charles put in.

“Yeah,” she said. “He said it was appro’prate that I leave from where the statue of my grandfather is. But you know, it doesn’t really look like him at all.

“So I started flying, and came through the black clouds, and that’s when the Compass Rose brung…um…”

“Brought,” supplied John.

“Right. That’s when it brought me here,” said Laura Glue. She looked around at the tattered remains of the

Indigo Dragon

. “Hey—who broke your Dragonship?”

“That was me,” said Jack. “I had to rescue Aven.”

“Excuse me,” said Aven, “but there was more to the situation than just saving me. It’s not my fault the tower was falling apart.”

“Now, now,” Charles said placatingly. “Let’s not be placing blame. We should be looking to the

Geographica

to get out of here, should we not?”

Aven threw one last poisonous look at Jack before nodding her head. “You’re right. Let’s get back to our plan. I…”

Aven stopped. The moment Jack had mentioned her, Laura Glue fell silent, and had been staring at the queen with platter-shaped eyes.

“You,” Laura Glue said reverently, “you’re a Mother now, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” Aven replied, unsure what the girl really meant by the question. “But once I was your friend, remember?”

“I remember who you look like,” said Laura Glue. “But you weren’t a Mother. Not then.”

Aven knelt before the girl and took her hands. “We used to play together, you and I. We had tea parties, and pretended we were wolves, and once I broke my arm, and you carried me to safety.”

Laura Glue’s mouth dropped open in surprise. She took her hands and traced the lines of Aven’s face, then fell forward, hugging her and sobbing. Aven was startled, but after a moment, she hugged the girl back.

“Poppy!” Laura Glue gasped through a sheen of tears. “It’s you, isn’t it? You’ve come back at last, and…and you’re a

Mother

.”

“Poppy?” Jack said, looking askance at Bert, who shrugged.

“It’s the first I’ve heard of it,” said Bert. “Although as I understood it, all the children who went to the Nether Land chose their own names.”

“We do,” said Laura Glue, who had wiped her nose on her sleeve before Charles could give her a handkerchief. “T’anks anyway, Charles,” she said, tucking it in her belt.

“Well, I don’t know about the rest of you,” said Jack, “but I’m rather anxious to get a look at this ‘Nether Land’ myself. Shall we get to it?”

“Of course,” John said.

“Oh!” exclaimed Laura Glue. “I almost forgot!”

She reached inside her belt and pulled out a note written on a familiar cream-colored paper that seemed to be favored among

Caretakers. Beaming, she handed the slightly crumpled paper to John.

The others crowded close as he unfolded it and read:

John—

While our young friend Laura Glue was showing me her wings, we discovered something else that had been left behind in your automobile. I trust it has now come to you in a timely manner, and that you will find it helpful.

The message she brought was sent by Peter, and thus must involve the Nether Land, and the Lost Boys. And these days, there is only one way in.

The words to open the passage are on page 42.

Godspeed to you all.

Sir James Barrie

John opened the

Geographica

to the spread of the page Jamie had indicated. “That looks awfully familiar,” he said pensively. “Is this actually an island in the Archipelago?”

Bert pressed closer and peered over his glasses. “It must be, although I’ve never been there myself.”

The island was shaped like a broad cup, wide at the top, narrowing to a tight neck, then widening again to a small base. The legend above identified it as “Autunno.”

“Autunno,” said John. “Italian, from a Latin base. Autumn. The island is called Autumn.”

“Hm,” said Bert. “I don’t recall ever needing to go there, although Stellan may have. But it looks ordinary enough.”

“It’s Hell,” said Charles.

“What?” the others said in a chorus.

“Hell,” Charles repeated. “Or at least, Sandro Botticelli’s version of Hell.”

Bert snapped his fingers. “Beat me with a noodle—he’s right. The cartographic image is that of an island, but the shape and topographical details match exactly the painting Botticelli did of Hell for Dante’s

Inferno

.”

“That makes sense,” said John. “The Cartographer said that Dante was one of the only Caretakers who visited the Underneath.”

“Fine,” said Jack, “but how does it apply to finding the Underneath?”

“I think it

is

the Underneath,” replied John. “The coordinates for Autunno are exactly the same as those for the Chamenos Liber. So it stands to reason that it is precisely where we’ve been told it is—Underneath, being guarded by the Chamenos Liber.”

“Can’t Autunno also be translated as ‘Fall’?” asked Jack.

“I don’t like the sound of

that

,” said Charles.

“Mmm, possibly,” said John. “I’m not as practiced with Italian, especially in this rough script. Give me a few minutes and I’ll have all the text sorted out.”

“Italian?” Jack asked Bert as John moved to the foredeck for privacy. “Dante wouldn’t have written his annotations in Latin?”

Bert shook his head. “Remember that Dante, for all his faults, was also a communicator. Most of the poems of the time were classified as ‘high’ for the serious topics, or ‘low’ for the vulgar ones. He thought it was a mistake not to write about the grander themes in a language that was more accessible to the common people.

“So when he chose to write an epic about the redemption of man, a subject of utter gravity and great import, he shocked most

of civilized society by doing it in Italian. His tendency to do the contrarian thing was probably one of the reasons he was selected as a Caretaker.”

“Indeed,” said Charles. “That’s an exceedingly noble and Romantic notion. Romantic with a capital

R

, that is,” he added.

“How so?” asked Bert.

“I believe that as human beings, we are all connected to one another, and in that way, largely dependent on one another for survival. A belief,” he said, observing the fauns still at work repairing the balloon at one end of the deck, and John translating Dante’s notes at the other, “that has only grown stronger during this adventure.

“I call the concept Co-inherence,” Charles continued. “What that means is that each of our thoughts and actions has a bearing on others. And always, always, there is potential in us all for immense good, or incredible evil. But even then, despite the evil men do, there can still arise a measure of good.”

“Yes,” agreed Bert. “Remember the Cartographer said not to judge even Mordred too harshly.”

“Exactly my point,” said Charles, “but the reverse is also true, and even the best of intentions…”

“…can pave the road to Hell,” finished John, who had just approached them, cradling the

Geographica

. “I think I’ve translated all of Dante’s notes. The solution to opening the portal to the Underneath is a riddle.”

“Jamie couldn’t simply tell us the words to open the portal?” Jack said.

“I don’t think it’s as easy as all that,” said John. “There must

have been some reason that we needed the actual

Geographica

here. And I think that reason is what the answer to the riddle will reveal.

“Dante wrote a lot about Autunno here,” he went on, indicating the annotations in the atlas, “but he also included bits and pieces from his own writing, so he obviously expected whoever followed him to be familiar with his work.”

“Typical author,” said Charles.

“He refers to the portal as ‘Ulysses’ Gate,’” John noted. “Does that mean anything to you, Bert?”

“Of course,” said Bert. “Ulysses was in

The Divine Comedy

, remember? In it he told the story of his final voyage, where he left his home and family to sail to the ends of the Earth.”

“I think this would qualify,” said Jack.

“Indeed,” said Bert. “Ulysses valued nothing more than his belief in the pursuit of knowledge, and he thought that attaining knowledge was limited only by one’s efforts.”

“Admirable,” said Jack. “So what happened to him?”

“God sank his ship outside of Mount Purgatory,” Bert answered, “and he ended up in the Pit.”

Charles raised his hand. “Anyone else thinking this is all a bad idea, and we should just focus on repairing the boat? No?” He lowered his hand. “Don’t say I didn’t bring it up when we get to the running about and screaming part.”

“We already did that,” said Jack, “when we escaped from the tower and I rescued Aven.”

“Not that I’m not grateful,” said Aven, “but I wish you’d stop bringing that up. I was perfectly willing to sacrifice myself so the rest of you could carry on.”

“And what good would that have done?” Jack said indignantly.

“For starters,” Aven told him, “the

Indigo Dragon

wouldn’t have been wrecked. And you’d already have been halfway to Paralon to bring more help.”

“And you’d be dead,” said Jack. “I just couldn’t let that happen.”

“And I’m appreciative,” said Aven. “But if our positions had been reversed, I’d have done the same.”

Jack smirked and shook his head. “There wasn’t time.”

Aven stared at him. “What’s

that

supposed to mean?

You

had time to save

me

.”

“Of course I did,” said Jack matter-of-factly. “I’m a man. We’re made to think more quickly.”

Bert had just enough time to exclaim, “Oh, dear,” before Aven swung her fist and clocked Jack square on the chin, knocking him backward into the balloon, which was still under repair.

“Wow!” said Laura Glue. “You sent him ass-over-teakettle.”

“Language,” warned Bert.

“Sorry,” she said.

Aven rubbed her knuckles and looked at the others. “Sorry about that. I might have stopped myself from hitting him, but I didn’t think of it quickly enough.”

“Not a problem,” said Charles.

“If you’re finished with the fisticuffs,” John said, “can we please see this through?”

“Sorry,” said Aven.

“Ulysses wasn’t the only Greek hero mentioned in

The Divine Comedy

,” said John. “In what Dante described as the eighth circle

of Hell, he and his guide, Virgil, met Jason, the leader of the Argonauts, who had commissioned the building of the ship the

Argo

—”