The Search for the Red Dragon (11 page)

Read The Search for the Red Dragon Online

Authors: James A. Owen

“I want to ask you something,” the king said, his voice soft. “I want to ask if you will look after Aven. As a personal favor to me. And I’m not asking as king or anything. Just…me. Artus.”

Jack started. He looked at the other man for a moment before answering. “Why are you asking me? Of course, all of us—”

“I know all of you will be looking out for one another,” Artus interrupted, “but that’s not what I’m talking about.

“I…I know how you felt about her, Jack. Before. I guess I’ve always known. So I hope you are not offended that I ask. To the others, she’s a companion and a friend. But of all of them, only you would understand this request from someone who truly loves her.”

Jack could see it in the young king’s face. He did love Aven, deeply. And it took more courage to ask this of Jack, his onetime rival for her affections, than Jack believed he could have mustered had their positions been reversed.

“Of course I will, Artus.”

“Thank you, Jack,” Artus said, offering his hand.

Jack didn’t hesitate to take Artus’s hand and grip it tightly with his own. “I’ll bring them back, Artus. Both of them.”

It wasn’t until he had walked out of the Great Whatsit toward where the others awaited him that Jack realized how much he meant the words he’d just spoken.

He did mean to bring back Aven and her son…

But not necessarily back to

Paralon

.

Aboard the

Indigo Dragon

once more, Aven instinctively slipped into command, as her father perceptively, subtly, stepped aside. The crew were accustomed to her, and indeed, seemed to step livelier to their tasks under her direction.

Bert nodded contentedly and leaned against the forward spars as the airship lifted free from its moorings and rose into the air above Paralon.

The smoke had been mostly cleared by the easterly winds, but a light haze remained, and the moon rose, unfocused, into the first frame of its nightly show.

Charles, feeling a bit peckish, announced that he was going to go rummaging around in the galley below for something to eat. He was joined by Bert, who claimed to have learned a recipe from Tummeler for an exceptional millet and barley soup.

“Good old Tummeler,” Charles said as he opened the door and

began descending the steps. “I’ve often thought about having him for a visit to Oxford and London—I think he’d have a marvelous time. It’s just that…”

“Difficult to explain a talking badger?” said Bert.

“Actually,” confided Charles, “I was more worried about him getting wet. The smell, you know.”

John stayed above, in part because he enjoyed the feeling of flight, but also to observe Jack. Since the trip had begun, neither he nor Charles had so much as mentioned Jack’s turbulent feelings regarding the death of his friend in the Great War. Everything had been moving at such a breakneck pace that it seemed to have been overlooked that Jack’s sleeplessness had begun long before the crisis in the Archipelago. There were larger beasts to be grappled with in his friend’s soul, and John was worried that if no one was watching, they might eventually devour Jack from the inside out.

In their last voyage through the Archipelago, it had been John who was traumatized by the events of the war and who felt a profound loneliness at being separated from his wife. But then, he had been older to begin with, and had more life experience than Jack in the four years that separated their ages. So coming to the Archipelago as a Caretaker of the

Geographica

was cathartic. It compelled him to find strengths he barely knew he possessed.

But Jack had come there with a different set of perceptions—and then saw a friend die as a result of his own choices and actions. There was no way for someone else to gauge how that might affect a man, especially when yet another friend was later lost in battle, and there was no real family to return to, to ground oneself.

Without turning around, Jack chuckled. “I can feel your eyes burning holes in my back, John,” he said. “I know you’re concerned about me, but you needn’t be. I can take care of myself.”

“Of that I have no doubt,” John assured him, sitting next to the railing. “But your friends are here to support you, Jack, in whatever way you need. And remember, I have some understanding of what you’re dealing with.”

Jack started to retort, then caught himself and grinned wryly. “Nine years ago I might have argued with you. But I’ve realized in recent years that I sometimes argue just for the sake of arguing. I wonder why I do that?”

“It’s part of what makes you a good teacher,” said John.

“Maybe,” said Jack. “But with my students, I tend to win every time. It’s not exactly fair.”

John smiled. “You just need to learn the difference between arguing for arguing’s sake and arguing when there’s a point to be made. If it’s the latter, then it won’t matter if it’s fair. Just if it’s right.”

Jack looked at his friend for a moment, then turned back to the sea and sky, watching.

The moon was fully above the horizon now, and it dominated the sky, turning the seas to cream and dispelling the last of the vaporous clouds that had obscured a sky of distant fireflies.

“It wasn’t Warnie,” Jack said suddenly.

“What wasn’t Warnie?” asked John.

“It wasn’t Warnie who began to call me ‘Jack.’ It was my own idea. Came to me in a dream when I was a child, actually. I just woke up and announced to my family that I was to be addressed as ‘Jack’ from then on. Sometimes it was ‘Jacks’ or ‘Jacksie,’ but Jack

was what stuck, and Warnie was the first to pick it up. But I came up with the name myself.”

John furrowed his brow and grinned wryly. “Then why tell us Warnie came up with it? What’s the difference?”

Jack shrugged. “I don’t know. I supposed I just felt ill at ease telling anyone about the dreams. Maybe more so after recent events. The dreams I had about Aven, and the Giants…Well, those were similar. But this time, no one was whispering that I should change my name.”

“Well, if it’s any consolation,” John said, “I’ve never gone by ‘John’ in my entire life. I’ve always preferred ‘Ronald,’ but the military used my full name, and there were times when propriety required that I be introduced as ‘John,’ and so that’s how Professor Sigurdsson came to know me. And then you fellows, of course. But there’s no one else in the world who knows me as John.”

“We’re not really in the world, in case you hadn’t noticed,” Jack noted.

“Point taken.”

“So would you rather we called you Ronald?” asked Jack.

John shook his head. “I don’t think so. Being ‘John’ is something I’ve come to associate with the

Geographica

and our travels together, and it’s almost as if I’ve become a different person here. So John is fine.”

“How about you?” Jack said, turning to Charles, who had just emerged from the galley licking his fingers. “Anything you’d like to share about your name or names?”

Charles cleared his throat. “Well, I once wrote a play, starring myself, in which I assumed the identity of a great adventurer,

modeled after Baron Munchausen, whose name was Brigadier-General Throatwarbler-Mangrove. I tried to coerce my friends to refer to me as ‘Brigadier-General,’ or at least ‘TM,’ but it never really took.”

Jack’s eyes goggled. “That’s amazing.”

John laughed and snorted. “How old were you when that idiotic idea crossed your mind?”

“It was last month,” said Charles, looking slightly put out.

“Sorry,” said John.

“You’d have been in fine company,” Bert said as he emerged from the cabin with two steaming mugs of millet and barley soup. “Baron Munchausen wasn’t his real name either,” he said, handing a mug to Charles.

“Really?” said Charles. “What was it?”

Bert puffed his cheeks and blew on the hot soup. “Ramon Felipe San Juan Mario Silvio Enrico Smith Heathcourt-Brace Sierra y Alvarez-del Rey y de los Verdes. But we all called him Lester.”

“Dear God.” Charles shook his head. “I’m sorry I asked.”

The night passed uneventfully, although Aven’s expression grew darker every time she noted the lack of ships on the great expanse below them.

Bert, Aven, and the crew knew the way to the smaller archipelago, where the keep was located, well enough to make consulting Tummeler’s

Geographica

unnecessary. This was a reprieve for John, who was hoping that his error in leaving the real atlas in London wouldn’t come up.

“We’re approaching the islands,” Aven said. “We should give

the center a wide berth—remember the steam, from the volcanic cone? That will play havoc with the airship.”

“She can’t quite bring herself to call it ‘the

Indigo Dragon

,’” Bert said to Jack. “Still too attached to the old one, I’m afraid.”

Aven tossed aside Jack’s copy of the

Geographica

and snorted. “These children’s books are more a threat than anything. They don’t note things important to navigation, and they skip too many of the dangers in the Archipelago.”

“Tummeler probably worried that it would be bad for sales,” Charles offered helpfully. “It’s the publisher’s dilemma.”

“We’d probably better keep to the original,” Aven said, turning to John. “That’s what it’s for, after all.”

“Ah, about that,” John began.

“Oh, my stars and garters!” Bert exclaimed. “I don’t think this is a problem that can be dealt with by reading the

Imaginarium Geographica

.”

The others crowded around the starboard side of the ship’s railing to see what the old man was talking about. Just ahead, in the creeping light of morning, they could see the silhouettes of the necklace-shaped ring of islands amidst the ever-present steam.

The stone columns of granite were just as the companions remembered them—with one stunning exception.

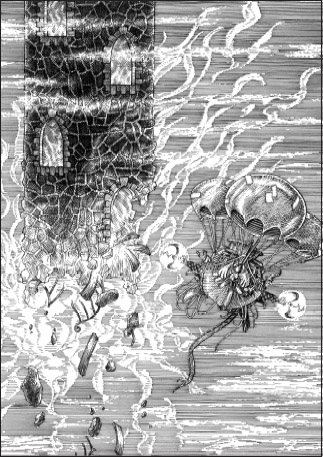

“The Keep of Time,” Bert said in astonishment. “It’s gone.”

High above them, like a great gray comet…

HAPTER

T

EN

The Tower in the Air

The largest of the islands,

where the Keep of Time had previously stood, was stark and barren.

Aven piloted the airship in a lazy circuit around the island so they could take a better look. Where the tower had been were a few scattered loose stones, but no indication of the foundation. It was if the tower had simply been removed.

“It seemed perfectly fine when we left it,” said Charles. “I don’t know what could possibly have happened to it.”

“I’m beginning to,” John said slowly as he paced the deck. “True, it

was

fine—but that was the second time we left, remember?”

As one, the companions all realized what John was referring to, and suddenly the Morgaine’s cryptic answers began to make much more sense.

The Keep of Time had been an immense tower, inside of which were stairways leading upward to a seemingly infinite number of doors. Each one opened into a point in the past, with those at the bottom leading to the times most distant in prehistory, and they advanced chronologically as one ascended.

Near the top, the stairs ended at a platform just short of the last door. That door opened into the future and was forever out of

reach. Thus, the tower was constantly growing in tempo with the progression of Time.

The next-to-last door, behind which they found the creator of the

Imaginarium Geographica

, who was known as the Cartographer of Lost Places, was the only one that opened to the present. But behind the fourth door from the top, John had found he was only in the recent past—and indeed, had a conversation with his dead mentor, Professor Sigurdsson, there.

After John’s encounter with the professor, and their subsequent meeting with the Cartographer, the companions had descended the stairway to find their adversary, Mordred, the Winter King, had arrived on the island as well.

And he had set the base of the keep on fire.

The companions had gone in the only direction they could—up—and as they climbed, Charles conceived of the plan that would ultimately save them all.

He proposed opening the door below the Cartographer’s and escaping into the immediate past. And sure enough, the door opened into the entrance at the base of the tower—one hour before the Winter King arrived. The companions then simply boarded their ship and left.

Aven stared at the island in shock. “We left safely, but an hour later Mordred still came here, and he still set the fire.”

“It never occurred to me that the Winter King might still have stormed the tower,” said Bert. “I always assumed he’d looked for us, not found us, and simply begun to pursue us again.”

“Same here,” said John. “Everything came to such a head on Terminus that I didn’t stop to think of what had gone before.”

Charles was mortified. “You…you mean it’s my fault the

tower was destroyed?” His legs began to wobble and he sat heavily on the deck, his head in his hands.

Bert laid a reassuring hand on his shoulder. “You aren’t to blame, Charles. Mordred’s actions were his own. You were the hero—you actually thought of a way to escape, when no one else had an answer. Mordred had already started the fire. After we escaped, he simply did it again.”

Bert’s words had no effect on an inconsolable Charles. “I destroyed it,” he murmured, disbelieving. “I destroyed the keep….”

He sat up straighter. “Worse! I destroyed

Time

. That’s what the Morgaine were talking about. I actually wiped out an entire

dimension

.”

“This really is some kind of extraordinary achievement,” John said supportively. “Not many people can lay claim to having broken Time, and we did it purely by accident.”

“Oh, I don’t think it’s as bad as all that,” said Bert. “Time is sturdier than you’d think. But I do believe we’ve found the source of the crisis.”

“Shouldn’t there be debris?” asked John. “I mean, even if the tower was burned, shouldn’t it have left a huge pile of rubble? A bunch of scorched stones?

Something

?”

“It wasn’t an ordinary tower,” Bert replied. “It was actually

made

of Time—well, and granite, and, er, ragthorn wood. But there’s no telling how it would be affected.”

As John, Charles, and Bert debated, Aven noticed that Jack was on the opposite side of the deck and hadn’t been looking at the island at all.

“What are you looking at, Jack?” she asked. “You’ve been staring at the water since we got here.”

“Look at this,” Jack said, waving her over without taking his eyes off the sea below. “There, just below us, see? That dark impression in the water? Could it be some sort of submarine, like the

Yellow Dragon

?”

Aven squinted and peered down to where Jack was pointing. “It’s not a ship—it’s a shadow. See, where the airship is casting a similar shadow on the water, and how it changes position with the light?”

“Huh,” said Jack. “Whatever’s casting that is a great deal bigger than the

Indigo

…”

Jack stopped and swallowed hard. He and Aven looked at each other as a sudden realization occurred to them. Then, together, they looked straight up.

“Oh, shades,” said Jack.

Charles was just starting to collect himself when Jack and Aven rejoined the others. They were both grinning like Cheshire cats.

“What?” said John. “What are you two smiling about?”

“Good news,” announced Jack. “Charles didn’t destroy the tower after all.”

“Not all of it, anyway,” said Aven.

“I’m confused,” said Bert.

As if on cue, the

Indigo Dragon

circled around to a point opposite the island and the risen sun—and the broken shadow that split the sea to the northern horizon fell across the airship.

The companions and crew all looked upward and saw what was casting the shadow.

High above them, like a great gray comet frozen in its descent to Earth, was the Keep of Time.

“Oh, thank God,” said Charles.

As the airship began to ascend, it occurred to the companions more than once that what they were attempting would have been impossible with any of the other Dragonships—including the original

Indigo Dragon

.

In terms of distance, the tower was only perhaps two miles above them. But if that measurement were applied to the portion of the keep that had been consumed by fire, then it represented thousands, perhaps even millions of years of history.

The

Indigo Dragon

approached the lower part of the floating tower and confirmed their supposition. It was jagged and charred, and the damage rose several hundred feet higher, then stopped. At some point, something had stayed the advance of the flames, but the damage done was inconceivable.

Aven guided the ship higher, to a point considerably past the charred portions, and at Bert’s direction threw an anchor line through one of the windows that opened into the stairway. Once secured, they maneuvered close enough to tether a rope ladder fashioned from the old ship’s riggings (“We kept some of it out of nostalgia, you know,” said Bert), and one by one they began to climb across.

Inside, the keep was exactly as they remembered it, save for the haze that obscured what remained of the lower levels.

“Watch your step,” Bert warned. “Wouldn’t be advisable to slip off the stairs.”

“You’re a master of the obvious,” said Jack.

“You’re the Caretaker Principia,” Aven said to John. “Lead on.”

Together, the companions began to climb.

It took sustained climbing for most of the day to reach the uppermost doors. The tower was silent except for an occasional rumbling noise that emanated from below.

“Forgive the sentiment,” said Charles, panting slightly, “but I almost wish the fire had burned up

more

of the place, so we wouldn’t have quite so far to walk.”

“I’m with Charles,” said Jack. “I still don’t understand why we couldn’t just fly the ship higher and enter a window closer to the Cartographer’s room.”

“Because,” Bert said, “the Keep of Time is also a judge of character. Remember how the last time the descent seemed to take less time than the climb up? That’s because it did. And do you recall the door we stepped through for our escape?”

“Right,” said John. “When we went through, it opened up down below only an hour earlier from when we’d entered.”

“It took us where and when we needed to go,” Bert affirmed, “because we earned it by our efforts. We could have flown higher, true—but I suspect it would not have shortened the distance we needed to climb.”

As if on cue, the ceiling seemed suddenly closer, the stairway ended, and the next door bore the keyhole that marked the room where they would find the Cartographer.

“You’re welcome,” Bert said to no one in particular.

As before, the door was locked—but Aven, as queen, had a ring that bore the seal of the High King. A touch was all it took. There was a soft click as the lock disengaged, and the door swung inward.

The Cartographer of Lost Places was sitting at his desk, concentrating on a very elaborate map.

“If I’ve told you once, I’ve told you thrice,” he said, irritated, “I haven’t the faintest idea who killed Edwin Drood, so you can just stop asking. You wouldn’t be in this mess if you hadn’t started that dratted serial.”

“Edwin Drood?” John inquired, stepping forward into the densely cluttered room. “I haven’t asked you anything about Edwin Drood.”

The Cartographer frowned and peered at his visitors over the top of his glasses. “Really? Aren’t you the Caretaker Principia?”

“Well, yes, but…”

“Hold on a moment,” the Cartographer said. He hopped off his chair and strode over to John. “You’re not Charles.”

“Ah, that would be me,” said Charles.

“Really?” exclaimed the Caretaker. “How extraordinary. You used to be much more handsome.”

“What?” Charles sputtered. “But…but I’ve only seen you the one time.”

“Nonsense. You’ve been here plenty of times,” said the Cartographer. “Although I wish you’d get rid of that apprentice of yours. He’s a bad egg, that one. What was his name? Maggot something?”

“Magwich,” said Charles. “And that’s the first thing you’ve said that’s made sense.”

“Hmm,” said the Cartographer. “You really aren’t Dickens, are you?”

“None of us is,” Jack put in.

“It’s for the best,” the Cartographer said. “He was a clever fellow, but he had terrible judgment when it came to apprentices. First Maggot, then that explorer fellow who snuck into Mecca. Just asking for trouble, the whole lot of them.”

Bert moved in front of the others to try to get the mapmaker to focus. “Do you remember me, at least?” he asked.

The Cartographer tilted back his head. “Hmm. The Far Traveler, unless I’m mistaken, which is seldom. Yes, yes…I do know you. What year is it, anyway?”

“It’s 1926,” said Charles.

“Excellent to hear,” said the Cartographer. “It’s helpful to know Time keeps moving forward, even as the past vanishes into smoke and ash.”

“Um, about that,” Charles began before Aven stomped on his foot. She scowled and put a finger to her lips.

“We noticed there’d been a situation,” said Bert.

“Situation?” the Cartographer exclaimed. “More like a catastrophe, if you ask me. Someone set fire to the keep and burned up an awful lot of history. It burned for nearly six years, you know.”

“How did you finally manage to put it out?” asked Jack.

“Put it out? Me?” said the Cartographer. “

Hello

—didn’t you notice the lock on the door? I couldn’t lift a finger. Just had to wait it out.”

“How

did

it go out?” asked Bert.

The Cartographer sat cross-legged on the floor and indicated that the others should sit as well. “I think it went out when it reached the doors that opened up to the end of the Silver Age, or the beginning of the Bronze,” he said. “Around 1600 BC or thereabouts. That would have done the trick.”

“What happened at the beginning of the Bronze Age?” Charles whispered to John.

“Deucalion’s flood,” John replied.

“Yep,” said the Cartographer, winking at Charles. “Water out

the ying-yang. It also put out the Thera eruption, so it could certainly douse a little tower fire.”

“Well,” said Charles, “at least it stopped the damage before it could take the whole tower out.”

“Stopped?” the Cartographer said in surprise. “Slowed, maybe, but not stopped. The entire base of the keep is missing, or hadn’t you noticed? The fire may be out, but the foundation is gone, and the structure is fatally weakened. Stones continue to fall into the sea, and door by door, the tower is still vanishing. What remains is only here because it’s in the future—but our past catches up to us. It always does.”

“What happens when it finally gets to the top?” asked John. “What will happen to you?”