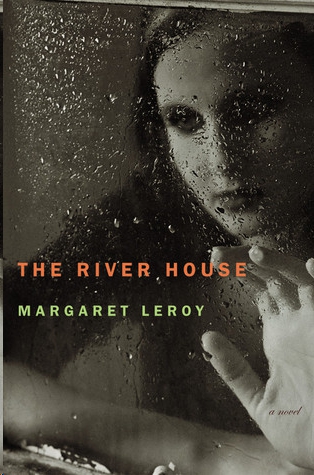

The River House

Copyright © 2005 by Margaret Leroy

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including

information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may

quote brief passages in a review.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook Edition: June 2009

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and

not intended by the author.

The author is grateful to Taylor & Francis for permission to quote the extract on page 145, which is taken from page 171 of

A Celtic Miscellany: Translations from the Celtic Literatures,

copyright 1951 by Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson, revised edition, Penguin 1971.

ISBN: 978-0-316-07710-1

Contents

ALSO BY MARGARET LEROY

Postcards from Berlin

HAPTER

1

H

E’S BUILDING A WALL FROM

L

EGO

. There’s no sound but the click as he slots the bricks together and his rapid, fluttery breathing. His face is white as wax.

I know he’s very afraid.

“You’re building something,” I say.

He doesn’t respond.

He’s seven, small for his age, like a little pot-bound plant. Blond hair and skin so pale you’d think the sun could hurt him,

and wrists as thin as twigs. A freckled nose that would wrinkle if he smiled—but I’ve yet to see a smile.

I kneel on the floor, to one side of him so as not to be intrusive. His fear infects me; the palms of my hands are clammy.

“Kyle, I’m wondering what kind of room you’re building. I don’t think it’s a playroom, like this one.”

“It’s the bedroom,” he says. Impatient, as though this should be obvious.

“Yes. You’re building the bedroom.”

His building is complete now—four walls, no door.

It’s a warm October afternoon, syrupy sunlight falling over everything. My consulting room seems welcoming in the lavish light,

vivid with the primary colors of toys and paints and Play-Doh, and the animal puppets that children will use to speak for

them, that will sometimes free them to say astonishing things. The walls are covered with drawings that children have given

me, though there’s nothing of my own life here—no traces of my family, of Greg or my daughters, no Christmas or holiday photos;

for the children who come here, I want to be theirs alone for the time that they’re with me. The mellow light falls across

Kyle’s face, but it doesn’t brighten his pallor.

He digs around in the Lego box, looking for something. I don’t reach out to help him; I don’t want to distract him from his

inner world. His movements are narrow, restricted; he will never reach out or make an expansive gesture. Even when he’s drawing,

he confines himself to a corner of the page. Once I said, Could you do me a picture to fill up all this space? He drew the

tiniest figures in the margin, his fingers scarcely moving.

He finds the people in the box. A boy and an adult that could be a man or a woman: just the same as last time.

“The people are going into your building. I’m wondering what they’re doing there.”

He’s grasping the figures so tightly you can see his bones white through his skin.

I feel a slight chill as a shadow passes across us. Instinctively, I turn—thinking I might see someone behind me, peering

in at the window. But of course there’s nothing there—just a wind that stirs the leaves of the elms that grow at the edge

of the car park.

There’s a checklist in my mind: violence, or sex abuse, or something he has seen—because I have learned from years of working

with these troubled children that it’s not just about what is done to you, that what is seen also hurts you. I know so little.

His foster parents say he’s very withdrawn. His mother could have helped me, but she’s on a psychiatric ward, profoundly depressed,

not well enough to be talked to. The school staff were certainly worried. “He seems so scared,” said the teacher who referred

him to the clinic. “Of anything in particular?” I asked. “Swimming lessons, story time, male teachers?” She had riotous, nut-brown

hair, and her eyes were puzzled. I liked her. She frowned and fiddled with her hair. “Not really. Just afraid.”

“Perhaps a bad thing happened in the bedroom,” I say now, very gently. “Perhaps the boy is unhappy because a bad thing happened.”

Noises from outside scratch at the stillness: the slam of a door in the car park, the harsh cries of rooks in the elms. He

clicks the figures into place. The sounds are clear in the quiet.

“You can talk about anything here,” I tell him. “Even bad things, Kyle. No one will tell you off, whatever you say. Sometimes

children think that what happened was their fault, but no one will think that here.”

He doesn’t respond. Nothing I say makes sense to him. Yet I know this must be significant, this room with the child and the

adult, over and over. And no way out, no door.

Perhaps this is the detail that matters. I sit there, thinking of doors. Of going through into new, expectant spaces: of that

image I love from

Alice in Wonderland,

the narrow door at the end of the hall that leads to the rose garden. Maybe he needs to experience here in the safety of

my playroom the opening of that door. I feel a surge of hope. Briefly, I thrill to my imagery of liberation, of walking out

of prison.

“Perhaps the boy feels trapped.” I keep my voice very casual. “Like there’s no way out for him. But there is a way. He doesn’t

know it yet, but there is a way out of the room for him. He could build a door and open it. All that he has to do is to open

the door. …”

He turns so his back is toward me, just a slight movement, but definite. He rips a few bricks from his building and dumps

them back in the box, as if he’s throwing rubbish away. His face is blank. He stands by the sandpit and digs in the sand with

his fingers and lets the grains fall through his hands. When I speak to him now, he doesn’t seem to hear.

After Kyle has gone, I stand there for a moment, looking into the empty space outside my window, needing a moment of quiet

to try to make sense of the session. I watch as Peter, my boss, the consultant in charge of the clinic, struggles to back

his substantial BMW into rather too small a space. The roots of the elms have pushed to the surface and spread across the

car park; the tarmac is cracked and uneven.

The things that have to be done tonight pass rapidly through my mind. Something for dinner. The graduates’ art exhibition

at Molly’s old school. Soy milk for Greg and buckwheat flour for his bread. Has Amber finished her Graphics course work? Fix

up a drink with Eva. … A little wind shivers the tops of the elms; a single bright leaf falls. I can still feel Kyle’s fear:

He’s left something of it behind him, as people may leave the smell of their cigarettes or scent.

I sit at my desk and flick through his file, looking for anything that might help, a way of understanding him. A sense of

futility moves through me. I wonder when this happened—when my certainty that I could help these children started to seep

away.

I have half an hour before my next appointment. I take the file from my desk and go out into the corridor.

HAPTER

2

L

IGHT FROM THE HIGH WINDOWS

slants across the floor, and I can hear Brigid typing energetically in the secretaries’ office. Clem’s door is open; she

doesn’t have anyone with her. I go in, clutching the file.

“Clem, d’you have a moment? I need some help,” I tell her.

Her smile lights up her face.

Clem goes for a thrift-shop look. Today she looks delectable in a long russet skirt and a little leopard-skin gilet. She has

unruly dirty-blond hair; she pushes it out of her eyes. On her desk, there’s a litter of files and psychology journals, and

last week’s copy of

Bliss

, in which she gave some quotes for an article called “My Best Friend Has Bulimia.” We both get these calls from time to time,

from journalists wanting a psychological opinion; we’re on some database somewhere. She gets the eating disorder ones, and

I get the ones about female sexuality, because of a study I once did with teenage girls, to the lasting chagrin of my daughters.

In a welcoming little gesture, Clem sweeps it all aside.

“It’s Kyle McConville,” I tell her.

She nods. We’re always consulting each other. Last week she came to me about an anorexic girl she’s seeing, who has an obsession

with purity and will only eat white food—cauliflower, egg whites, an occasional piece of white fish.

“We’ll have a coffee,” she says. “I think you need a coffee.”

Clem refuses to drink the flavored water that comes out of the drinks machine in the corridor; she has a percolator in her

room. She gets up and hunts for a clean cup.

“When does Molly go?”

“On Sunday.”

“It’s a big thing, Ginnie. It gets to people,” she says. “When Brigid’s daughter went off to college, Brigid wept for hours.

Will you?”

“I don’t expect to.”

“Neither did Brigid,” she says. She pours me a coffee and rifles through some papers on a side table. “Bother,” she says.

“I thought I had some choc chip cookies left. I must have eaten them when I wasn’t concentrating.”

She gives me the coffee and, just for a moment, rests her light hands on my arms. It’s always so good to see her poised and

happy. Her divorce last year was savage: There were weeks when she never smiled. Gordon, her husband, was very possessive

and prone to jealous outbursts. She finally found the courage to leave, and was briefly involved with an osteopath who lived

on Wesley Street. Gordon sent her photos of herself with the eyes cut out. About this time last year, on just such a mellow

autumn day, I took her to pick up some furniture from the home they’d shared, an antique inlaid cabinet that had belonged

to her mother. Gordon was there, tense, white-lipped.

She looked at the cabinet. She was shaking. Something was going on between them, something I couldn’t work out.

“I don’t want it now,” she said.

“You asked for it, so you’ll damn well take it,” he said.

As we loaded it into the back of my car, I saw that he’d carved “Clem fucks on Wesley Street” all down the side of the cabinet.

She sits behind her desk again, resting her chin in her hands. There are pigeons on her windowsill, pressed against the glass;

you can see their tiny pink eyes. The room is full of their throaty murmurings.