The Ride of My Life (7 page)

PERMANENT RECESS

Hooking up with the Skyway team put me one step closer to the lifestyle I lusted for: touring, hitting all the contests, and spending as many hours a day as possible on my bicycle. From the time I was twelve years old, I’d dreamed of riding for a living, and at age fifteen I found myself in a fairy tale that had come true. Sort of.

A shady-looking Ford conversion van tooled slowly down our winding gravel driveway, kicking up clouds of dust. The van was painted metallic blue, and stickers adhered to various surfaces. From a distance, it resembled something a band of retired people might drive on a fishing trip. But the vehicle was towing a Skyway-logoed quarterpipe and a launch ramp, on a trailer stacked with bikes. I’d been anxiously awaiting their arrival and when they pulled up, I got a lump in my throat. This was it—welcome to the big time, kiddo. The first day of my first tour

.

Doors opened and everybody stumbled out, fatigued and goggle-eyed after pulling a twenty-hour long haul from California to Oklahoma City. This rig would be my home for the next couple of months, and, well…it smelled like feet. The same way a seasoned homicide detective knows the stench of death, any biker who has ever gone on the road can identify “Tour Smell.” It’s the gamy, fungal funk of humans trapped in a sweaty metal box, living on fast food and truck stop beef jerky. My compatriots for the next several thousand miles greeted me with wolf howls, jive handshakes, and high fives.

There was Maurice “Drob” Meyer, a twenty-year-old power rider who’d honed his pro class skills on the streets of San Francisco. Eddie Roman, the sixteen expert ramp/flatland/joke-cracker extraordinaire from San Diego, followed Drob. And finally, there was Skyway’s golden boy, Scotty Freeman, a top-ranked fifteen expert flatlander with the flashy smile and polished style of a child actor. The man in charge of our traveling circus was Ron Haro, the twenty-one-year-old team manager and younger brother of the legendary inventor of freestyle, Bob Haro. Ron was the driver, responsible guy, and show announcer. He was also a mischievous party starter who went by the

nickname Rhino. Rhino traveled with an extensive collection of wacky hats and considered himself “a professional idiot.” It was his job to get the crowds riled up and cheering, even if it meant looking stupid so his team could look cool.

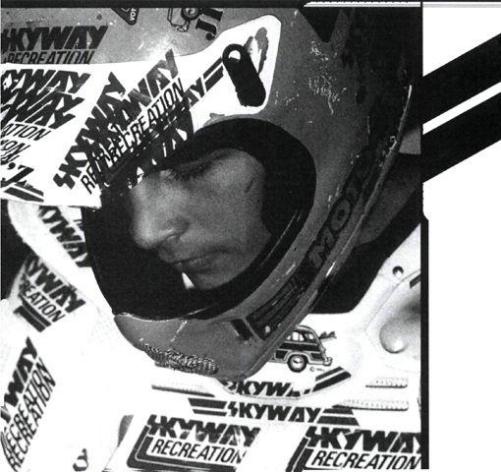

I got into bikes straight from motorcycles, so a chest plate and full-face helmet were the norm for me. For a while, it tripped people out in the bike scene to such overprotection, but I put my gear to good use. I was also obsessed with stickers. (Photograph courtesy of Steve Giberson)

These guys were my posse, and we were in for a tour that would take us through twenty-five states with fifty show dates. My family stepped out onto the lawn to see the grand entrance, and my mom was at the ready with provisions for the gladiators—an industrial-sized box of snacks and goodies. The Skyway team caught a swim and some rest, and then we crammed my stuff into the van. It was time. I gave my family hugs, and they waved us off.

As the van drove down the driveway toward our first stop, I looked out the window as my house got smaller and smaller. My family was still waving on the front lawn, and my mom and dad looked a bit teary-eyed to see me shipping off for uncharted waters. They were also really stoked for me. They’d had such a big hand in my career, and this was a turning point. I was about to start doing what the guys in the magazines did—take my show on the road.

The modus operandi was the same for each performance: pull up to a bike shop parking lot and get greeted by hundreds of sunburned superfans who’d been standing on hot blacktop for hours. We’d set up the ramps and PA system—the Skyway ramps featured a simple one-piece flip-up design and were good to go in ten minutes. Then for the next hour, sometimes hour and a half, the crowd was wowed with every stunt we could bust, on the ground and in the air. Rhino would slap on a propeller beanie or a foam shark fin and scream himself hoarse. The crowd reciprocated. Afterward, the team would sign some stuff, toss some stickers, and be off—to a budget hotel, or, if it was a tight schedule, toward another town with another bike shop and another sea of kids, sometimes two thousand people deep. It was, in a word, awesome—if you like being surrounded by strangers asking you all sorts of questions.

Me, I was painfully shy. I don’t think I had full-blown agoraphobia, but it definitely freaked me out being the focal point for hundreds of people I didn’t know. Growing up, I was seldom around anyone besides my family and a tight circle of friends. As I began traveling around the country, I was exposed to a lot of new experiences, and it was tough for me. I liked hanging out with the guys on my team, and I met some cool people … but it would take years before I learned to relax in public [I still prefer being withdrawn in social situations]. I think one of the reasons I spent so much time on my bike—besides the fact that I loved riding—was because I didn’t have to talk much. I could remain anonymous beneath my full-face helmet, do some airs, and let my actions speak on my behalf. Ironically, the more I rode, the louder I was communicating, and the more people paid attention to what I had to say.

Paranoia would overwhelm me whenever I had to travel solo. I would go to great lengths to avoid having to hang out among strangers, like pretending to sleep in my hotel room and not answer the phone or the door. It was stupid.

All these feelings of bashfulness came to a boil on a trip to England for the International BMX Freestyle Organization World Championships. It was my first time overseas; I was alone, didn’t know anybody, and was hating it. The event was sponsored by Tizer, some weird British beverage, and it took place over the course of a week in seven places around England, climaxing with made-for-TV finals held in Carlisle. There were TV cameras everywhere, and each day I had to psych myself up to make it to the contests, knowing I would have to mingle, chitchat, and explain my actions for European television. I felt really timid around my fans, and as soon as the riding was over, I bolted straight to my tiny six-by-ten-foot dorm room. As I sat in my room staring at the wall, bored out of my skull, I realized something had to change. If I didn’t learn to be a little more outgoing, my life was going to be pretty dry. During the week, I forced myself to

interact with the promoters, fans, and other riders. Gradually, I began to shed my fear of being in the limelight. I’d also been crowned the Supreme Amateur Ramp Champion of the World (whatever that meant]. They also held a contest between all the winners of the week’s events, and I won that, too. I was declared the Champion of the Champions.

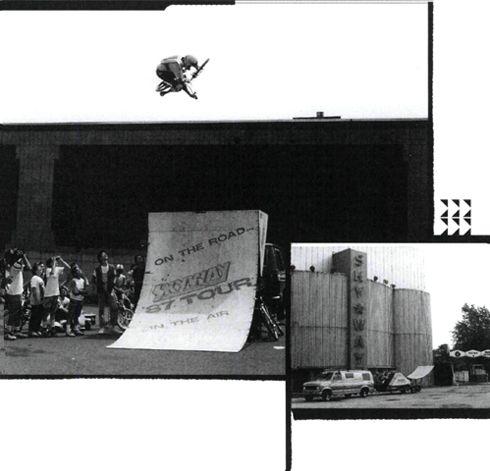

This was the first show I did with Kevin Jones. My goal that day was to clear the building.

That summer I also got the opportunity to tour in a series of shows featuring a special all-stars team. Dannon Yogurt was launching a new product called Dan-Up and was promoting the goop using flying bike riders. The shows were cosponsored by the “Just Say No” antidrug foundation. I flew in to amphitheaters, schools, and parks around the country and hooked up with Eddie Fiola, Rick Moliterno, Gary Pollak, and Dennis McCoy. We’d click airs, gulp yougurt, and just say no for the local TV news crews. It was weird, but fun. The Dan-Up demos were where I got my first taste of meeting famous people. At the Los Angeles show, I got to hang out with Soliel Moon-Fry, the girl who played Punky Brewster on the eighties TV sitcom. The same day we rode for the Queen of Just Say No, Nancy Reagan. I think I must have been riding a little out of control that afternoon, because as soon as I started my runs, the secret service agents plucked Mrs. Reagan out of the crowd and far away from the runway. Just say whoa.

Skyway wanted the maximum number of kids exposed to their new marketing tool (me), so I was sent to just about every major freestyle contest from Alabama to western Canada. Usually my mom and dad, my friend, Steve Swope, and a sibling or three accompanied me. I rode hard at each comp and began picking off wins, building a reputation. Victory was kind of cool, but not my main focus. As I started getting media coverage, I was irked by details that came out in the press. Like when the magazines critiqued the way I really went off in practice—skying as high as I could and throwing in stretched variations—but then noted that when I was being scored, my runs were raw, especially when compared with the tightly choreographed routines of some competitors. I was also fairly notorious for the music I rode to at AFA contests—typically some vintage Dr. Demento-style novelty rock, like “Flyin’ Purple People Eater.” To me, riding was riding, and it didn’t matter when and where it went down, whether it was “practice” or “real.” As long as I tried my hardest and went the highest, I was content. Usually that alone was enough to win the 14-15 Expert Ramps category. After I landed my first magazine cover, the coveted front page of Freestylin’ magazine, there was no turning back. Everybody in the sport knew who I was, and I had become public property. People wanted to see me ride, to see if the hype was true. Media coverage put the zap on my head; I’d read a caption or description of my riding abilities, and they’d paint a picture of this figure that I could never live up to—but I felt like I was expected to anyway. I didn’t yet understand the difference between reality and hype. It wasn’t until later that I learned to deal with it when Public Enemy let me know, “Don’t. Don’t believe the hype.”

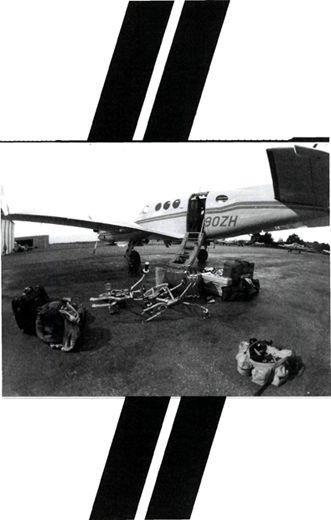

This was the life. I got to pilot the plane between takeoff and landing, then go to a comp and ride. (Photograph courtesy of Steve Giberson)

My favorite part about the contest scene was the feeling of being immersed in bike riding, bonding with my friends one epic weekend at a time. Contests were about seeing the new tricks, kicking a little ass on the ramp, heckling my teammates, and at the end of the day, getting goofy at the Denny’s dinner tables. All that began to change midway through 1987, at an AFA event in Columbus, Ohio. It was the biggest AFA contest to date, about 260 riders strong. Eddie Roman and I were amusing ourselves (and no one else] using a homebrewed geographic joke: With a cheerful expression, we’d approach other riders and exclaim, “Oh. Hi!

Oh

…”

The sport was booming, and the influx of new riders meant the manufacturers were pumping a lot of cash into freestyle bikes, tours, and teams. Each month the number of kids seemed to multiply and companies added to the sport, defining it with a contagious energy. T-shirts and ’zines were being created, forming the bike subculture that surged up from the underground. At the Ohio comp, it was evident how popular riding had become in a short time. There were thousands of spectators, and hundreds of bikers who swarmed like lemmings to the contest-some didn’t even compete, they just came to ride.

Ohio was one of the first contests where the extracurricular activities surrounding the competition overshadowed the event itself. Rebellion was in the air. Big parking lot flatland jam circles and all-night street riding were becoming the norm. Despite the best efforts of AFA president Bob Morales and his affiliates around the country, the riders at AFA events wanted more than just a contest. They wanted a scene.